Antarctica's ocean-front glaciers are retreating, according to a new satellite survey that raises additional concerns about the massive continent's potential contribution to rising sea levels.

Antarctica, which contains enough ice to raise the oceans by about 200 feet (60 meters), is a continent of ice that flows outward to the ocean at numerous large glaciers.

These mostly submerged glaciers rest deep on the seafloor at a point called the "grounding line", where ocean, ice and bedrock meet.

But at 10.7 percent of these glaciers, the ice masses are moving at a significant speed back toward the center of the continent as they melt from below, often because of the incursion of warm ocean water, which causes the grounding line to retreat.

Only about 1.9 percent of glaciers were growing at a significant speed, suggesting a net retreat.

And the more glaciers are retreating, the more one worries about sea-level rise. Retreating grounding lines can expose more ice to the ocean, allowing it to flow outward more rapidly.

Here's a brief video of the process provided by the authors of the new study, which was published in Nature Geosciences:

The research used satellite techniques to infer changes to glacier grounding lines based on changes in the height of the glacier's surface.

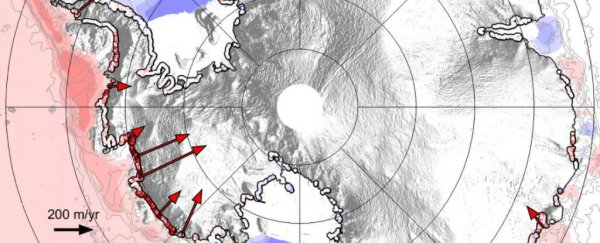

Scanning one-third of Antarctica's marine-based glaciers along a roughly 10,000-mile (16,000 km) stretch of coastline, the work presents a more comprehensive look than other studies of Antarctic glaciers, which have tended to focus on grounding lines in just one key region.

"We were able to quantify more or less all around Antarctica," said Hannes Konrad, the lead author of the research. Konrad works at the University of Leeds in Britain, along with a number of co-authors of the study. Other authors worked at University College London.

The research found that from 2010 through 2016, about 80 square miles (200 square km) per year of ice is being lifted off of the seafloor and going afloat as grounding lines retreat. That's about four times the size of Manhattan every year.

At the same time, the 10.7 percent of Antarctic grounding lines were retreating at a rate faster than 25 meters per year, which the study takes as a benchmark because that rate of retreat is believed to have occurred at the end of the last ice age.

Just 1.9 percent of Antarctic grounding lines were advancing faster than 25 meters per year.

The sea-level implications of the research are troubling, if not direct - researchers cannot precisely quantify sea-level rise just based on the retreat of grounding lines, although they are certainly related.

"We find that 10 percent of the Antarctica ice sheet significantly retreating, but we can't somehow extrapolate sea level rates that come from that," Konrad said.

"But to say 10 percent of Antarctica, this massive ice body, is retreating, still should be some sign of warning. It's large."

A key factor driving the retreat of Antarctic grounding lines is the incursion of warm, deep ocean water which melts glaciers at their bases and causes the grounding line to retreat.

The situation is the worst in West Antarctica, something that has been widely known and that the new research confirms.

The enormous Thwaites glacier - which has the potential to unlock several meters of sea-level rise if it retreats entirely into the center of West Antarctica - was found to be retreating at 300 to 400 meters per year along a 25-mile central section of the glacier.

The study also found that Thwaites's retreat had increased between 1996 and 2011.

"Imagine other coastlines changing at an equal speed, that's really massive," Konrad said of what's happening to Thwaites.

Science agencies in the United States and Britain are mobilizing an urgent mission to study Thwaites up close, because of the belief among scientists that it could be the one glacier with the greatest potential to remake world coastlines in coming decades and centuries.

"We focus especially on Thwaites because sufficiently large retreat there could evacuate the entire central region of the West Antarctic ice sheet, perhaps raising global average sea level more than 3 metres through that one outlet," Richard Alley, a glaciologist at Penn State University, said in an emailed comment on the study.

In West Antarctica, more than 20 percent of grounding lines were retreating faster than 25 meters per year. In East Antarctica, which contains massively more ice, the percentage was considerably lower - and some areas, which are receiving more snowfall, are seeing grounding lines advance.

But the largest East Antarctic glacier, Totten, is an exception and is indeed showing a fast rate of retreat, the study confirmed.

Finally, in the Antarctic peninsula, which contains the least ice, 10 percent of grounding lines were retreating faster than the 25 meter-per-year rate.

Eric Rignot, an Antarctic expert at the University of California at Irvine, who has also documented grounding-line retreat in key parts of the continent, said by email that "the grounding line is an essential indicator of glacier change in Antarctica, and this study brings important information about the rates of changes and geographic distribution."

Penn State's Alley, who was also not involved in the research, added that the new work "generally confirms our understanding - increased snowfall is contributing to locally small, slow advances of grounding lines in some places, and increased temperature of offshore ocean water is contributing to large, rapid retreats of grounding lines."

He said the next step will be for scientists to plug data such as these into simulations that will let them better calculate precisely how much the sea-level-rise risk is from Antarctica going forward.

"This new study thus is an important step in the long-term effort to learn the future of the ice sheet," Alley said.

2018 © The Washington Post

This article was originally published by The Washington Post.