A tick-borne disease that kills up to 30 percent of infected people has been caught spreading locally in western Europe for the first time.

So far in the current outbreak, only two people have been infected - one fatally - in Spain, but the European Centre of Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC) is now warning travellers and hikers, as well as healthcare and agricultural workers, to avoid contact with ticks and potentially infected animals across western Europe.

"We are targeting risk exposure groups such as livestock farmers and hunters who frequently come into contact with animals," Herve Zeller at the ECDC told Andy Coghlan from New Scientist.

"They can be in contact with ticks, and by crushing them it can allow the virus through their skin," he added.

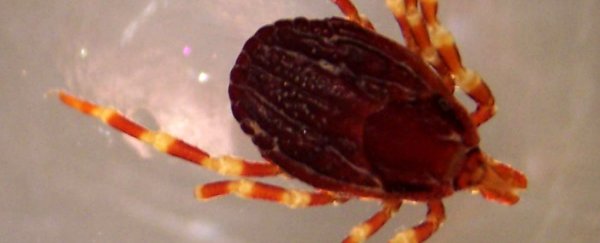

The disease is known as Crimean-Congo haemorrhagic fever (CCHF) and is most commonly spread by the Hyalomma genus of ticks, which live on livestock across Asia, Europe, and Africa.

Luckily for animals, they rarely present symptoms after CCHF infection, but when humans become infected, it can cause extreme fever, vomiting, nose bleeds, and black stool. Within two weeks, 30 percent of patients infected will be dead.

There's currently no vaccine against CCHF, and although it's usually spread by tick bites, it can also be transferred through bodily fluids - and is often caught by abattoir workers who come in contact with animal blood regularly. This year alone, 20 people have died from CCHF in Pakistan.

While the disease is already endemic (which means it spreads locally) in Africa, the Balkans, the Middle East, and Asia, this is the first time it's been documented in western Europe. Previous cases in the area had always been brought in from overseas.

The first person infected in the local outbreak was a 62-year-old hiker, who was bitten by a tick near Ãvila in Spain.

He died from CCHF on August 25, but not before the virus was transmitted to a 50-year-old healthcare worker who treated him in Madrid - most likely through contact with his blood.

Local doctors put roughly 200 other healthcare workers under observation for symptoms to stop the disease spreading further, and the healthcare worker is now showing signs of recovery.

In a report on the two cases, the ECDC suggests that the virus was most likely brought to Spain by birds migrating from Morocco, or other parts of northern Africa. Once in Spain, the ticks would have moved from birds to livestock and other animals, spreading the disease with them.

The good news is that the virus has been detected in animals near the Spanish/Portuguese border since 2010, but has taken this long to spread to humans because we're not their prey of choice, which suggests the risk isn't too high.

"This virus has been present in these areas since 2010, but we have only one spread case in five years, so it's a rare event," Zeller told New Scientist.

"[Hyalomma ticks] are found in southern France and Spain, but people are seldom bitten and the main hosts in these countries are tortoises, lizards, cows, donkeys, hares and foxes," added Cheryl Whitehorn from the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine.

But low risk doesn't mean zero risk, and the ECDC is advising people travelling in western Europe to wear long pants, shirts, and insect repellent to avoid tick bites.

"The probability of CCHF virus infection in Spain is low. However, other sporadic cases are possible," their report concluded.

There are no established Hyalomma tick populations in the United States or the UK, so it's unlikely the disease will spread in those countries.