In the northern constellation of Ursa Minor, a star is dying. It's not going quietly, either.

It's wracked by 'coughs' that send shockwaves expelling its outer material into the space around it. And this is giving us a glimpse of what's going to happen to our own Sun, in just a few billion years.

The star is red giant T Ursae Minoris (T UMi for short), and astronomers have determined that it's just erupted in a thermal pulse that only comes around every 10,000 to 100,000 years.

"This has been one of the rare opportunities when the signs of ageing could be directly observed in a star over human timescales," said astronomer Meridith Joyce of the Australian National University.

T UMi is actually in a particular phase of a star's life known as the asymptotic giant branch (AGB), an evolutionary stage seen in stars that were initially up to eight times the Sun's mass.

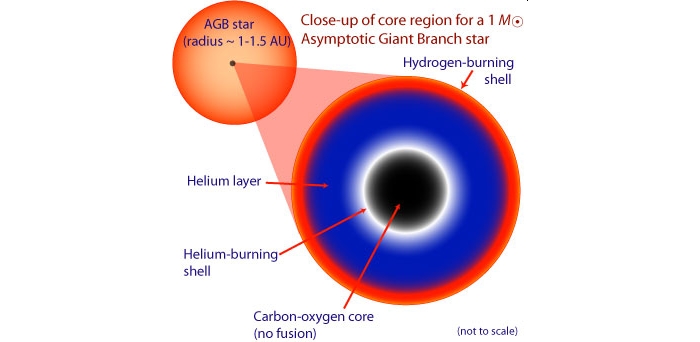

At this point, the star is already a red giant. Its core has run out of hydrogen, and has only carbon and oxygen left. At an earlier point in the AGB stage, a shell around the core fused helium into carbon.

When the helium runs out, a shell of hydrogen around that starts fusing into helium, replenishing the helium shell until it explosively reignites and starts fusing into carbon again. This event is the thermal pulse, also known as the helium shell flash, it can last up to a few hundred years.

(Australia Telescope National Facility/CSIRO)

(Australia Telescope National Facility/CSIRO)

Astronomers have been keeping a close eye on T Umi for over 100 years, carefully noting the length of its fluctuations in brightness. And, up until 1979, these fluctuations were pretty steady, sitting between 310 and 315 days.

But 1979 marked a turning point: its period fell dramatically to 274 days, and it's been steadily declining ever since.

In 1995, astronomers hypothesised that this sudden change was the result of a helium shell flash.

Now Joyce and her colleagues, with a couple more decades of observations under their belt, have determined that that is the case. Over the past 30 years, they have observed the star dwindling in size, brightness and temperature.

This, in turn, has allowed them to figure out more about the star itself. It is, they have determined, around 1.2 billion years old, and it was initially around twice the mass of the Sun.

For the last few million years, it has been undergoing these death throes, and this pulse is somewhere between 20 and 24 of an estimated 25 to 30 before the shells are exhausted of material, and the stellar core contracts into a white dwarf in a few hundred thousand years.

This is the fate we expect for our Sun, starting in about 5 billion years.

It will balloon out, dramatically dropping in density, engulfing the inner planets, and throwing off its outer material into a planetary nebula. It's not high-mass enough to produce a supernova - it'll end quietly, a white dwarf slowly losing its thermal energy until it's just a cold, dark, dead rock floating in space.

We won't be around for that. But we can keep watching T UMi, whose changes are so dramatic we can observe them in real-time.

"We'd expect to see it expanding again in our lifetimes," Joyce said.

"Both amateur and professional astronomers will continue to observe the evolution of the star in the coming decades, which will provide a direct test of our predictions within the next 30 to 50 years."

How mind-blowingly cool.

The research has been published in The Astrophysical Journal.