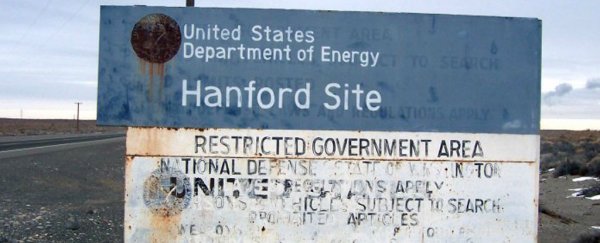

The Hanford nuclear site in Washington state - one of the largest and most contaminated storehouses of radioactive waste in the US - is currently undergoing an emergency.

Hanford, which is overseen by the US Department of Energy (DOE), is a Cold War-era facility that led US production of plutonium for use in tens of thousands of nuclear weapons.

The site no longer produces plutonium; however, millions of gallons' worth of radioactive waste is still stored there, and workers are carrying out a lengthy process of decommissioning the 586-square-mile (151,773 hectare) reservation - what the Associated Press dubbed "the nation's most contaminated nuclear site" in 2007.

The entire site was put under a precautionary "take cover" order on May 9, due to a cave-in of a tunnel containing radioactive materials.

Hanford later permitted most employees to leave, but those under lock-down near the tunnel have not yet been allowed to go home, according to a tweet by Susannah Frame, a reporter with KING television in Seattle.

What is the emergency?

DOE; Business Insider

DOE; Business Insider

On Tuesday morning at 11:26am EDT, the site posted an emergency bulletin that called on employees to evacuate and take shelter near "a former chemical processing facility" in its 200 East Area.

Specifically, the emergency is happening at a 200-acre (80 hectare) facility called the Plutonium Uranium Extraction plant, or PUREX.

Two long rail yard tunnels feed into the site. About half a dozen workers discovered the hole in earth covering one of the tunnels this morning, triggering their evacuation, said Destry Henderson, a spokesperson for the Hanford Emergency Center, during a live press briefing on Hanford's Facebook page.

"All personnel in the immediate area have been accounted for, they are safe, and there's been no evidence for a radiological release," Destry said.

"Upon an additional investigation, crews noticed a portion of that tunnel had fallen - the roof had caved in - about a 20-foot [6-metre] section of that tunnel, which is more than 100 feet [30 metres] long."

Mound of dirt that covers railroad tunnels to PUREX facility. Image: DOE

Mound of dirt that covers railroad tunnels to PUREX facility. Image: DOE

The later discovery of the roof cave-in triggered a broader safety alert.

"All of the employees on the Hanford site have been told to take cover. What that means is shelter-in-place," he said. "This is purely precautionary, because again, no employees were hurt and there was no spread, no indication of a spread of radiological contamination."

The incident may have led to a release of radioactive materials, but crews are still inspecting the site to find out.

What's inside the PUREX tunnels?

DOE; Business Insider

DOE; Business Insider

In the photo above, you can see the 20-by-20-foot-wide hole (6 by 6 metres) in one of two tunnels leading into the Hanford site's PUREX facility.

Soon after the collapse, Frame posted to Twitter that the tunnel is "full of highly contaminated materials, such as hot, radioactive trains that transported fuel rods".

Lynne T., a member of the joint information centre with the DOE who would not provide a last name, told Business Insider that "the tunnels do contain contaminated materials", though "there's no evidence of any injuries, and all employees have been accounted for. There's also no confirmation that any radioactive material has been released."

She said the Hanford Fire Department "is on the scene and investigating it, and everyone is being sheltered", adding that no one appears to be hurt at this time, and that approximately fewer than 10 people are currently inside the PUREX facility.

Frame is posting pictures from the site, including one of a TALON military-grade robot that's being used to determine whether or not there's a leak of radioactive materials:

This robot is being used at Hanford right now to sample contamination in the air and on the ground. pic.twitter.com/AFOrhIbB9S

— . (@SFrameK5) May 9, 2017

Some reports suggest that vibrations from nearby road work may have caused the tunnel roof collapse.

However, Destry said it's "too early to know what caused the roof to cave in", and that "we may not know that for some time".

What was the PUREX plant used for?

PUREX was the "workhorse" of Cold War-era production of plutonium-239 (Pu-239), a fissile material that can be used in bombs to create nuclear explosions.

Rods of uranium fuel were irradiated in nuclear reactors at Hanford to form Pu-239, then trained into PUREX for processing. The fuel rods were dissolved with acid to sort any plutonium from leftover uranium fuel and radioactive waste.

The plant "is longer than three football fields, stands 64 feet above the ground, and extends another 40 feet below ground," according to the Hanford website, and "[c]oncrete walls up to six feet thick were used in the plant to shield workers from the radiation of the building."

Furthermore, according to Hanford:

"Built in the early 1950's, the facility went into operation in 1956. From 1956 to 1972, and again from 1983 until 1988, PUREX processed about 75 percent of the plutonium produced at Hanford. Some scientists believe that more plutonium was processed at PUREX than any other building on the planet, as it processed more than 70,000 tons of uranium fuel rods during its operations.

"The building has been vacant for nearly twenty years, but it remains highly contaminated. Its walls are surrounded by razor wire and barbed wire fences. Several rail cars used to transport the irradiated fuel rods from the Hanford nuclear reactors to the processing canyons are temporarily buried inside a tunnel near PUREX as a result of becoming contaminated.

"As with the rest of the Hanford structures, PUREX is slated to be decontaminated, demolished, and some of its debris removed. The rail cars buried next to the facility will also be decontaminated, removed, and permanently buried.

Although, the option of grouting the rail cars in-place within the tunnel is being evaluated since removal of the cars would entail extreme worker safety hazards and would be more costly than grouting in-place."

Cleanup costs for the entire Hanford site may exceed $US113 billion, according to an estimate from 2014.

This article was originally published by Business Insider.

More from Business Insider: