A new study has found that US metropolitan areas are losing about 36 million trees every year across the entire country. That's equivalent to 175,000 acres of tree cover in central, suburban and exurban fringes.

Just as a growing number of Americans are choosing to live in cities, scientists have begun to discover the importance of living near trees for our health and wellbeing.

The problem is obvious, and only made worse when urban forests and green spaces in the US are being decimated at such an alarming rate.

To give some context, Central Park in New York City is about 840 acres. This means that every year, US cities are losing over 208 Central Parks.

The value of this loss is roughly equivalent to about US$96 million in benefits, according to lead author David Nowak of the US Forest Service (USFS).

And that number is quite conservative. Nowak said the final figure was based on "only a few of the benefits that we know about."

These include the ability of trees to remove air pollution, sequester carbon, conserve energy by giving shade to buildings and reducing power plant emissions.

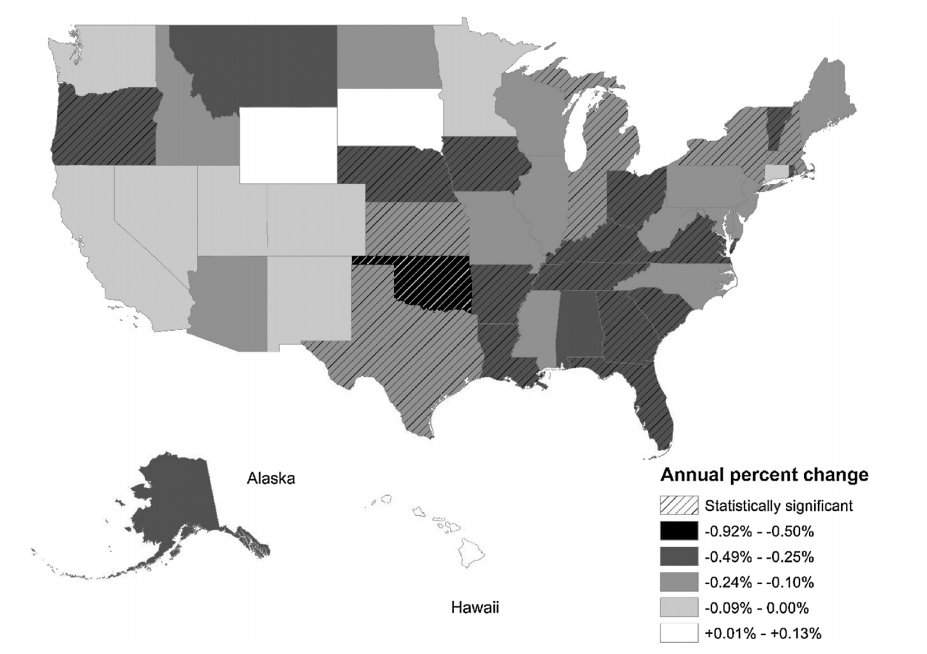

Nowak and his co-author Eric Greenfield from the USFS used paired aerial photographs from Google Earth to monitor forest coverage in 1,000 locations for each of the 50 states across the US from 2009 to 2014.

They found widespread devastation of urban trees and green spaces, with about 23 states experiencing a significant loss of tree coverage.

(Nowak and Greenfield)

(Nowak and Greenfield)

Percentage-wise, the states that experienced the greatest loss of trees were Rhode Island, Georgia, Alabama, Nebraska and the District of Columbia.

Of all 50 states, only three - Mississippi, Montana and New Mexico - experienced an increase in urban tree population, and all three were by "nonsignificant" amounts.

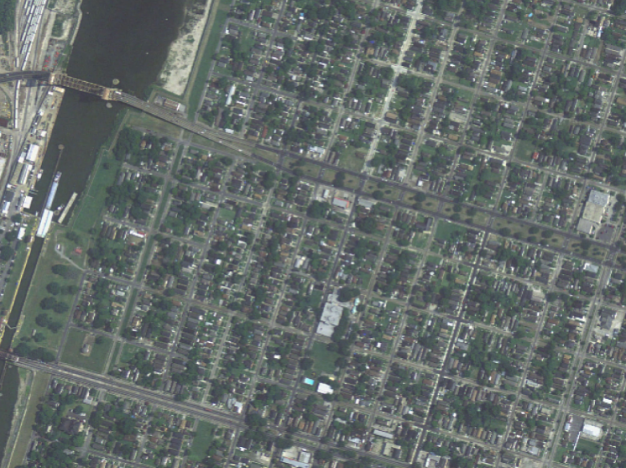

Nowak told Scientific American that he attributes the losses to the expanding urban population, the natural life cycle of trees, storms like Hurricane Katrina (which knocked out a third of New Orleans' shade trees), insect damage, individual property owners converting forests to lawns, and fires.

The study builds on a finding that was identified by the two authors just six years ago. Nowak and Greenfield's ground-breaking 2012 study found 17 out of 20 American cities had experienced significant tree loss.

These "before-and-after" images of New Orleans, which lost nearly 9 percent of its coverage from 2005 to 2009, were particularly startling.

2005 New Orleans (Nowack and Greenfield)

2005 New Orleans (Nowack and Greenfield)

2009 New Orleans (Nowack and Greenfield)

2009 New Orleans (Nowack and Greenfield)

Yet despite the worrying results, very little has happened to combat the environmental and public health issue. Nowak is worried about what will happen if the trend continues.

"If it keeps going down, I think we're going to be in trouble. Cities will warm up, we might have more pollution, people will be more unhealthy," he said.

There is robust evidence to suggest that trees are good for public health. In their presence, our blood pressure and heart rate can be reduced, as can our stress levels. Trees also have the power to boost mental engagement and attentiveness, comfort and happiness.

Still, it appears that the American public doesn't quite understand the seriousness of the problem.

"Too many people think that living in closer contact with nature is nice, it's an amenity, it's good to have if you can afford it," William Sullivan, who studies the effect of tree cover on urban crime and was not involved in the new study, told Scientific American.

"They haven't got the message that it's a necessity. It's a critical component of a healthy human habitat."

In many ways, the reality of climate change has woken city residents up to this message.

Eric Sanderson, a Wildlife Conservation Society ecologist, said he has found that people can be persuaded by the importance of trees when they hear that their city will be growing ever warmer in the coming years.

In California, for instance, shade trees were found to reduce the surface temperature of asphalt by up to 20 degrees C (36 degrees F), and of the passenger compartments of parked cars by 26 degrees C (47 degrees F).

As global warming begins to threaten urban metropolises, shade will become ever more valuable.

There's also water to consider. Many cities around the US use trees to capture and contain water to reduce runoff.

When trying to tackle storm water overflow in Philadelphia, for instance, the city ditched an expensive and temporary reservoir in favor of planting trees and installing green infrastructure.

In this case, the advantages from simply increasing urban green areas were found to be nearly 23 times greater than building the reservoir, yielding $2.8-billion in total benefits.

This figure took into account improved property values, increased recreational opportunities and avoided heat-stress deaths.

But right now, most American cities are doing the exact opposite of planting trees. Nowak and Greenfield's study also found that "impervious surfaces" - or surfaces that cannot soak up water, like asphalt - have increased in cities by 1 percent.

And to top it all off, around 40 percent of these new impervious areas were placed upon ground where trees once grew.

As cities across the US continue to expand and grow, residents, lawmakers and city planners will have to decide how they prioritize tree coverage.

In New York alone, the city has room for another 200,000 street trees, according to Jennifer Greenfeld, the city's assistant commissioner for forestry, horticulture and natural resources. The state of California has room for 236 million.

"Urban forests are an important resource," Nowak said.

"Urban foresters, planners and decision-makers need to understand trends in urban forests so they can develop and maintain sufficient levels of tree cover – and the accompanying forest benefits – for current and future generations of citizens."

The study has been published in Urban Forestry & Urban Greening.