The Hubble space telescope has seen a lot of weird things that defy easy definition. Here's one more for the list – a binary asteroid that's also a comet.

Astronomers have found a pair of them, in fact, swirling around one another in the asteroid belt while leaving a stream of dust in their wake. Not only is it a beautiful example of how nature DNGAF about our categories, it raises some interesting questions on how many of these hybrids might be out there.

The binary object itself was first spotted back in 2006 as part of the asteroid-searching Spacewatch program, resulting in it getting the not-so-glamorous name 2006 VW139.

It wasn't until 2012 that astronomers realised something odd about it; this thing that was an asteroid with comet-like characteristics, namely a streaming tail.

So-called main belt comets aren't new, but they're by no means common either. This asteroid is just one of about a dozen such objects ever discovered.

What makes this particular one so unique is that it's in two pieces.

2006 VW139 is made of a pair of equal-sized lumps orbiting one another at a distance of just under 100 kilometres (about 60 miles).

Why it split in half is an intriguing mystery, one that meant astronomers were desperate for a closer look.

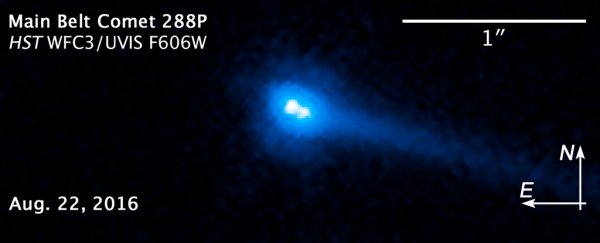

As the twins made their closest approach to the Sun last September, NASA turned the Hubble Space Telescope to capture clearer images of its nucleus and tail, confirming the signatures of a comet sitting where comets normally don't sit.

"We detected strong indications for the sublimation of water ice due to the increased solar heating – similar to how the tail of a comet is created," says team leader Jessica Agarwal of the Max Planck Institute for Solar System Research, Germany.

The researchers think 2006 VW139 split apart about 5000 years ago under the stress of rotation, where the stream of vapour coming off the pieces helped push them further and further apart.

For a time-lapse animation of the asteroid, check out the video clip below.

The big question that remains, however, is just how common systems like this one are in the inner Solar System.

"We need more theoretical and observational work, as well as more objects similar to this object, to find an answer to this question," says Agarwal.

Hopefully more of these oddball icy asteroids will be spotted as technology improves, revealing more beauty and detail amid the rock-studded expanse that is the asteroid belt.

The research is due to be published in the journal Nature.