Ever wanted to see what happens when you give octopuses drugs? Scientists in the US have just lived that dream. They gave a solitary, asocial octopus species MDMA, aka ecstasy, and watched rapt as the cephalopods tried to hug all up on each other.

The research, as weird as it may seem, actually yielded some important results, as the experiment demonstrated an evolutionary link between humans and octopuses in the way the neurotransmitter serotonin encodes social behaviour.

"Despite anatomical differences between octopus and human brain, we've shown that there are molecular similarities in the serotonin transporter gene," said neuroscientist Gül Dölen of Johns Hopkins University.

"These molecular similarities are sufficient to enable MDMA to induce prosocial behaviours in octopuses."

Over 500 million years separates octopuses from humans, which is when the two last had a common ancestor. But after the genome of the California two-spot octopus (Octopus bimaculoides) was sequenced and published, scientists suspected that human and octopus brains may work the same - in one specific way.

Octopus bimaculoides. (Tom Kleindinst)

Octopus bimaculoides. (Tom Kleindinst)

Researchers Dölen and marine and evolutionary biologist Eric Edsinger of the Marine Biology Laboratory discovered a genetic similarity between humans and octopuses.

In particular, the transporter that binds the neurotransmitter serotonin is nearly identical between humans and O. bimaculoides. Serotonin plays a role in mood regulation, feelings of happiness and wellbeing, as well as depression - and its activity is increased by MDMA.

MDMA is known for being a "happy" drug, increasing feelings of euphoria, as well as boosting one's feelings of empathy, and wanting to connect with others. And this hasn't just been observed in humans - mice and rats also want to bond with each other when under the influence.

Humans, rats, and mice are pretty social animals. Most octopuses, on the other hand, including O. bimaculoides, are known to be solitary, preferring their own company to that of their fellows.

As it turns out, they may be a little more social than thought, especially given a bit of neurochemical help. The researchers ran two experiments.

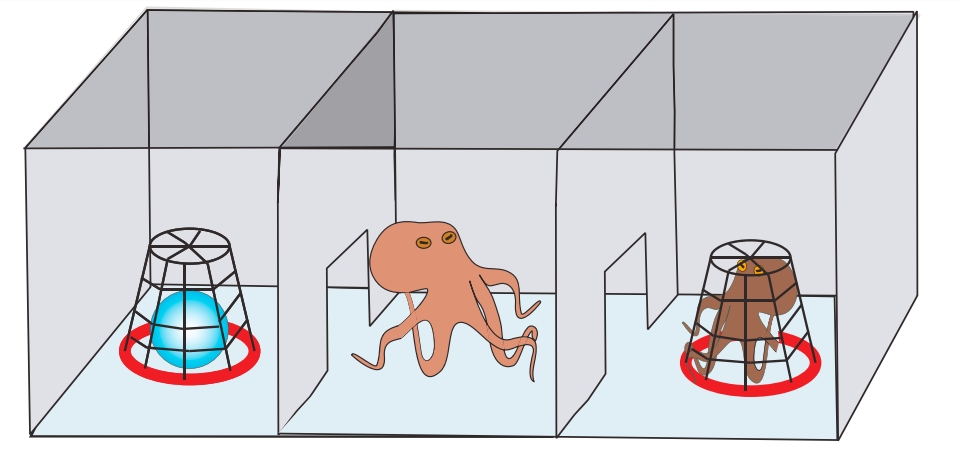

(Edsinger & Dolen/Current Biology)

(Edsinger & Dolen/Current Biology)

In the first, five male and five female octopuses were put in chambers. On one side, visible through a clear wall with a hole so the octopus could enter, was a novel object - a plastic action figure. On the other side, again separated by a wall with a hole, was another octopus, in a cage.

Without being drugged, all the octopuses, male and female, were interested in socialising with female octopuses, but not male ones. So they weren't super-social, but they were more social than they had previously been thought.

For the MDMA experiment, four male and four female octopuses were exposed to the drug, before being put in the experimental chamber for 30 minutes. This time, they spent more time with other octopuses - including males. And they made a lot of physical contact.

"It's not just quantitatively more time, but qualitative. They tended to hug the cage and put their mouth parts on the cage," Dölen said. "This is very similar to how humans react to MDMA; they touch each other frequently."

It doesn't just tell us more about the evolution of serotonergic signalling in the regulation of social behaviours - it's a finding that could help study and develop psychiatric drugs, particularly selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) antidepressants.

First, though, the results will need to be affirmed through further experiments.

Meanwhile, the researchers are sequencing the genomes of two other octopus species that behave differently from O. bimaculoides, in the hopes of shedding more light into how their social behaviours evolved.

As for the octopuses - who were hatched in the lab, not caught in the wild - they went through this entire trip just fine. The team adhered to guidelines as per the Animal Welfare Act, and afterwards the animals returned to their tanks in Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute in Massachusetts.

As Dölen explained to National Geographic, not only did the animals not show any signs of stress, but they even went on to have babies after returning home.

The research has been published in the journal Current Biology.