China's Yutu lunar rover mission has turned up something pretty special during its lonely survey of the Moon - a never-before-seen type of volcanic lunar rock, estimated to be almost 3 billion years old. Found in the little-studied Imbrium Basin, one of the largest known craters in the Solar System, the rock's mineral composition is unlike anything scientists have seen in a moon rock.

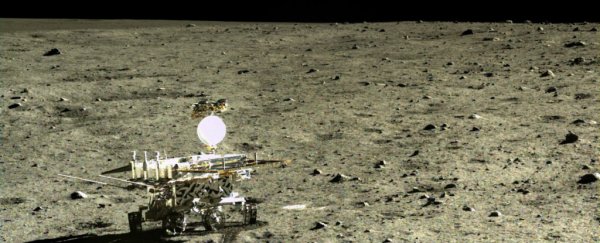

The Yutu rover, whose name means "Jade Rabbit", was the first spacecraft to land on the Moon since the US Apollo and Soviet Union Luna missions ended around 40 years ago. (Others have been deliberately crashed on the surface, but we can't really count those.) Having just passed its two-year lunar anniversary, Yutu is now the world's longest-serving lunar rover.

While information collected by past lunar orbiters has given scientists some idea of the different types of volcanic rocks that make up the surface of the Moon, this is the first chance we've had to sample them directly since the 1970s.

Having analysed data on the new type of moon rock - recorded by Yutu's on-board instruments - researchers from China and the US suspect it comes from a relatively young region, which was formed around 2.96 billion years ago.

With the Moon estimated to have formed around 4.5 billion years ago, and sprouting volcanoes 500 million years after that due to an internal build-up of heat from radioactive decay, the discovery will help us to better understand the behaviour of the Moon's long-gone but youngest volcanoes.

"The diversity tells us that the Moon's upper mantle is much less uniform in composition than Earth's," said one of the team, Bradley L. Jolliff from Washington University. "And correlating chemistry with age, we can see how the Moon's volcanism changed over time."

When moon rocks were sampled by the Apollo and Luna mission rovers back in the '70s, scientists had no way of getting accurate readings of the exact compositions. But thanks to Yutu having an alpha-particle X-ray spectrometer and a near-infrared hyperspectral imager equipped, Joliff and his colleagues from several Chinese research institutions have been able to figure out exactly how much titanium and iron is in their sample.

The titanium value in particular is really important, because it's a good indication of how, when, and where volcanic magma first formed on the Moon. "The variable titanium distribution on the lunar surface suggests that the Moon's interior was not homogenised," said Jolliff. "We're still trying to figure out exactly how this happened. Possibly there were big impacts during the magma ocean stage that disrupted the mantle's formation."

An added bonus in being able to properly analyse this new type of moon rock is that scientists can now use it as a baseline for observations recorded by spacecraft in orbit around the Moon. "We now have 'ground truth' for our remote sensing - a well-characterised sample in a key location," Jolliff explains. "We see the same signal from orbit in other places, so we now know that those other places probably have similar basalts."

The results have been published in Nature Communications.