Humans have pulled too hard on our planet's strings, and now we're at a point where the global climate itself is unravelling.

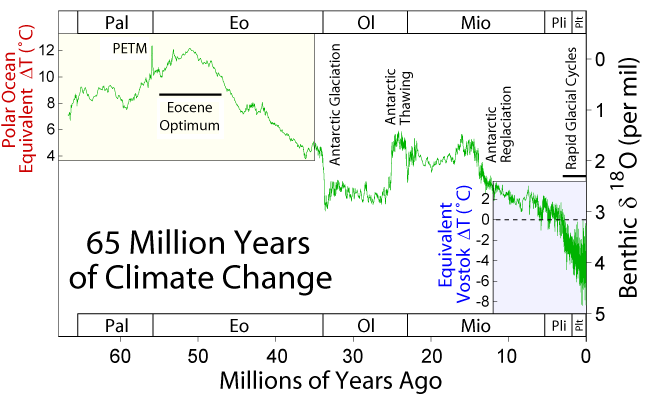

A new study suggests that if nothing is done to reduce our carbon emissions, we could essentially reverse 50 million years of long-term cooling in just a few generations.

The consequences could send us spiralling back in time by at least 3 million years. By 2030, the study predicts that Earth's climate may resemble the mid-Pliocene - the last great warm period before now, when the world was 1.8 degrees Celsius warmer (3.2 degrees Fahrenheit).

From that precarious spot, we could retreat even further. By 2150, the study suggests our climate could most resemble the ice-free Eocene of some 50 million years past, when there were extremely high carbon dioxide levels and global temperatures were roughly 13 degrees Celsius warmer (23.4 degrees Fahrenheit).

This is a time when crocodiles swam in the swampy forests of the Arctic Circle and palm trees dropped coconuts in Alaska.

"If we think about the future in terms of the past, where we are going is uncharted territory for human society," says lead author Kevin Burke, a paleoecologist at the University of Wisconsin-Madison.

"We are moving toward very dramatic changes over an extremely rapid time frame, reversing a planetary cooling trend in a matter of centuries."

Today, the accelerated rate of climate change is faster than anything the planet has ever experienced before. Now, we are so far off the road map that one of the only ways to figure out where we are going is to retrace the ancient steps the world took long, long ago.

Combing through Earth's climate history, the new study sought to identify a time that is similar to current climate projections.

To do this, the researchers picked out six climate benchmarks from throughout Earth's geologic history, dating as far back as the early Eocene to as recently as the early 20th century.

The team then compared these geological periods with two different climate scenarios, calculated using the best available data from the fifth assessment report from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC).

The first scenario is the worst case possible - a future in which humans do not mitigate greenhouse gas emissions at all - and the second scenario is one in which we do manage to moderately reduce emissions (a feat that will be difficult to achieve, given our current activity).

"Based on observational data, we are tracking on the high end of the emissions scenarios, but it's too soon to tell," says Burke.

Using no less than three different climate models, the researchers tested both of these scenarios, and then compared them to each of the geologic periods picked out.

The results are kind of like a 'choose your own adventure' book with only two options: we can either do nothing and end up with a climate that resembles the Eocene, or we can try and reduce our emissions and halt our climate at Pliocene conditions.

Under both of these scenarios and across each of the models, the results for the short term are about the same. By at least 2040, Earth's climate will most closely resemble the mid-Pliocene, and this is well beyond the "safe operating space" of the Holocene that we were shooting for.

At this point, no matter which way we slice it, it seems highly likely that our children and grandchildren will live to see a world where temperatures will rise, precipitation will increase, ice caps will melt, and the poles will become temperate.

During the Pliocene, the climate was arid and the High Arctic was home to forests in which camels and other animals roamed. Who knows what will happen to biological life and human society when the climate reverts to that state within just a few centuries?

(Wikimedia Commons)

The findings of the new study reveal that these rapid changes will probably begin at the centre of Earth's continents, spiralling outwards in concentric circles until they engulf the whole planet.

This means that in some areas of the world - for instance, the parts that lie at the centre of those circles - the climate consequences will be especially drastic.

"Madison (Wisconsin) warms up more than Seattle (Washington) does, even though they're at the same latitude," explains co-author John 'Jack' Williams, a researcher in ecological responses to climate change.

"When you read that the world is expected to warm by 3 degrees Celsius this century, in Madison we should expect to roughly double the global average."

But while we can predict some of these extreme climate changes, others will no doubt take us by surprise.

In the worst case scenario, by the stage that our climate once again resembles the mid-Pliocene, the research found that nearly 9 percent of the planet will be experiencing "novel" climates.

This means that in some areas of the world, including eastern and southeastern Asia, northern Australia, and the coastal Americas, humans will be experiencing climate conditions that have no known geological or historical precedent.

"In the roughly 20 to 25 years I have been working in the field, we have gone from expecting climate change to happen, to detecting the effects, and now, we are seeing that it's causing harm," says Williams.

"People are dying, property is being damaged, we're seeing intensified fires and intensified storms that can be attributed to climate change. There is more energy in the climate system, leading to more intense events."

It's difficult to put a positive spin on all of this, but the researchers tried their hardest. After all, life has a way of surviving and pushing through seemingly insurmountable challenges.

"We've seen big things happen in Earth's history – new species evolved, life persists and species survive. But many species will be lost, and we live on this planet," says Williams.

"These are things to be concerned about, so this work points us to how we can use our history and Earth's history to understand changes today and how we can best adapt."

This study has been published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.