A single tail from one of the largest and most enigmatic dinosaur species looks to have solved a longstanding mystery about these extinct creatures: whether they could swim.

The discovery of a giant fossilised tail belonging to the theropod Spinosaurus aegyptiacus suggests these huge predators were aquatic animals after all, using tail-propelled locomotion to swim and hunt in rivers millions of years ago.

"This discovery really opens our eyes to this whole new world of possibilities for dinosaurs," says palaeontologist Nizar Ibrahim from the University of Detroit Mercy.

"It doesn't just add to an existing narrative, it starts a whole new narrative and drastically changes things in terms of what we know dinosaurs could actually do."

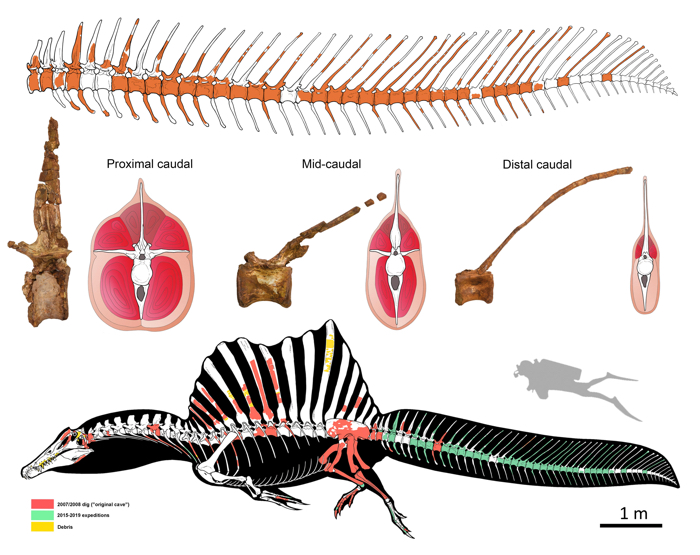

Reconstruction of tail and skeleton, plus cross sections of tail pieces. (Marco Auditore/Gabriele Bindellini)

Reconstruction of tail and skeleton, plus cross sections of tail pieces. (Marco Auditore/Gabriele Bindellini)

Centuries ago, scientists speculated that terrestrial dinosaurs may have dwelled in water environments, but in recent decades, the idea has fallen out of favour, with most researchers suggesting non-avian dinosaurs were limited to roaming on land.

Spinosaurs, however, have somewhat complicated the issue, with some ancient bones suggesting possible evidence of semi-aquatic adaptations.

In previous research, Ibrahim and his team made such a case, but other researchers weren't so sure.

Now, the palaeontologist is back, with what his team claims is the first "unambiguous evidence for an aquatic propulsive structure in a dinosaur".

That evidence consists of a giant fin-like tail, discovered in the Cretaceous rock deposits of the Sahara Desert in eastern Morocco.

Estimated to be between 90 to 100 million years old, the tail discovery fills in the picture on what Spinosaurus looked like, broadening our perspective on the world's only existing skeleton of the species (another was destroyed in World War II).

"This dinosaur has a tail with an unexpected and unique shape that consists of extremely tall neural spines and elongate chevrons, which forms a large, flexible fin-like organ capable of extensive lateral excursion," the researchers write in their paper.

In the study, the team examined the amount of thrust this structure could have generated when swimming through the water, and conclude the performance is comparable to living aquatic vertebrates with similar appendages.

In other words, Spinosaurus presents the best evidence yet that dinosaurs – or at least this particular species – might have swum.

"This discovery is the nail in the coffin for the idea that non-avian dinosaurs never invaded the aquatic realm," Ibrahim says.

"This dinosaur was actively pursuing prey in the water column, not just standing in shallow waters waiting for fish to swim by. It probably spent most of its life in the water."

The findings are reported in Nature.