Say we stopped emitting greenhouse gases overnight; by the year 2100, the world's oceans would still likely rise another foot and a half.

More realistically, we'll likely see seas get 2 or 3 feet higher.

The projected flooding from that sea-level rise threatens hundreds of millions of people and vast amounts of infrastructure along coastlines across the planet. Scientists have attempted to estimate the number of people at risk, but according to a new study, all those numbers have been far too low.

The research, published in the journal Nature Communications today, indicates that three times more coastal residents worldwide are vulnerable to sea-level rise and flooding than previous estimates suggested.

The two climate scientists behind the new study, Scott Kulp and Benjamin Strauss, work at the organisation Climate Central.

They concluded that 110 million people worldwide already live on land that's below the current high-tide line. About 250 million, meanwhile, occupy land below current annual flood levels.

What's more, their model shows that a significant number of people live just above today's high-tide line.

"There is a really huge concentration of population density in the very lowest strips of land, in the lowest places along the coast globally," Strauss told Business Insider.

"It turns out within those first couple of meters [above sea-level], there are more than 3 million people per vertical inch."

A quarter of a billion people worldwide live just above the high-tide line

In the 20th century, the average global sea level has already risen 6 inches (15 centimetres) due to warming waters and melting ice sheets. This has already led to more high-tide flooding (often called king tides or sunny-day floods).

This kind of flooding – unlike that from storm surges during extreme weather events like hurricanes – can happen any time ocean water surges to higher levels than coastal infrastructure was designed to accommodate.

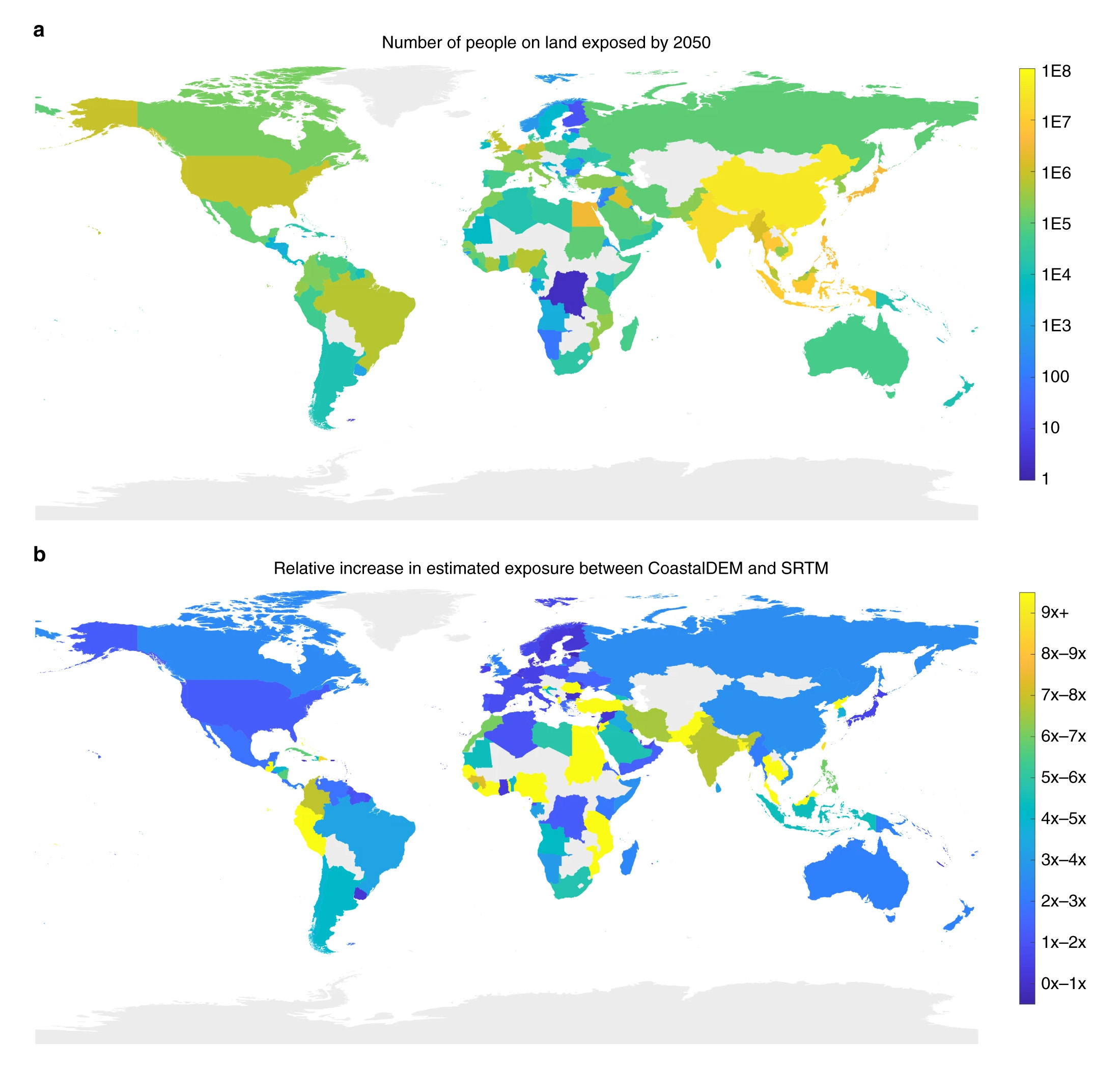

For the new study, the researchers looked at data from 135 countries across multiple emissions scenarios and timelines. Typically, international flood-risk assessments use data from NASA's Shuttle Radar Topography Mission (SRTM), which mapped the elevation of countries around the world from space.

But, according to Strauss, that data uses the tops of buildings as proxies for elevation, not the actual height of the ground those buildings sit on. So Strauss and Kulp used a new model designed to correct that discrepancy.

They found that, even under a highly optimistic scenario in which greenhouse-gas emissions peak next year then decrease, 190 million people would occupy land below sea-level by the end of the century.

If emissions continue to rise through 2100, that number could reach 630 million people globally. That's nearly double the current US population.

These numbers are triple the totals scientists would glean by using just the NASA data.

"We've elucidated that you can't measure flood risk by analysing the elevation of rooftops – you have to know the height of the ground beneath your feet," Strauss said.

Even more concerning, he added, is the number of people who currently live less than 32 feet (10 meters) above today's high-tide levels: 1 billion. Nearly a quarter of those 1 billion people live less than 3 feet (1 metre) above that line.

"The magnitude of the numbers speaks for itself," Strauss said.

The study results suggest that people in Asia – Indonesia in particular – are "disproportionately threatened by this issue."

Their model found that by 2050, 237 million people in China, Bangladesh, India, Vietnam, Indonesia, and Thailand could face annual coastal flooding threats. By 2100, if emissions continue unchecked, that number could reach 250 million.

Total populations on vulnerable land. (Kulp & Strauss, Nature, 2019)

Total populations on vulnerable land. (Kulp & Strauss, Nature, 2019)

Sea levels could rise 3 feet by 2100

A recent report from United Nations' Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) also suggested that our current estimates of future sea-level rise may be too low.

If Earth's temperature increases by more than 3 degrees Celsius, the authors found, water levels would be an average of 3 feet higher by the year 2100.

The planet's average temperature has already gone up by 1 degree Celsius, and sea levels have risen globally by about 6 inches (15 centimetres). But the rise is accelerating, the report found.

The IPCC report suggests that by the end of the century, higher seas are likely to displace or affect 680 million people in low-lying coastal zones and about 65 million citizens of small island states. Strauss said his new study builds off these results.

The primary cause of sea-level rise, according to the IPCC, is the melting of the Antarctic and Greenland ice sheets, which are melting six times faster then they did four decades ago.

Roughly 1.7 million square kilometres (656,000 square miles) in size, the Greenland ice sheet covers an area almost three times that of Texas. Together with Antarctica's ice sheet, it contains more than 99 percent of the world's fresh water, according to the National Snow and Ice Data Centre.

If the entire Greenland ice sheet were to melt – granted, this would take place over centuries – that would cause a 23-foot (7 metre) rise in sea level, on average. That's enough to submerge the southern tip of Florida.

If both Antarctica and Greenland's ice sheets were to melt, sea levels would rise more than 200 feet (61 metres). Florida would disappear.

Rising ocean temperatures (the seas absorb 93 percent of the extra heat trapped on Earth by greenhouse gases) also cause sea levels to rise regardless of ice melt, since water expands when heated.

"The biggest take-home message is: The number of people who will be threatened by sea-level rise this century is extraordinary," Margaret Williams, managing director of the World Wildlife Fund Arctic Program, previously told Business Insider.

According to Strauss, these new estimates should serve as motivation to address that threat now.

"Even as we show there's a far greater threat from sea level rise, we now know that there are far greater benefits to cutting emissions," he said. "This new data can be a useful tool for cities and countries to plan better for the future their coastal populations are facing."

This article was originally published by Business Insider.

More from Business Insider: