An anti- cancer drug that's currently on the market has shown potential in halting the first stages of Alzheimer's disease, and researchers are now looking at developing a treatment that can be taken as a preventative measure long before symptoms develop.

The results have so far only been seen in animal models, but it's hoped that the drug could bolster the natural immune response in humans to prevent the build-up of toxic amyloid clumps - thought to be the key driver of Alzheimer's disease.

A team from the University of Cambridge in the UK worked with genetically modified worms that were engineered to develop Alzheimer's disease. At various stages of the disease, the worms were given the cancer drug, bexarotene, which has seen mixed results in treating Alzheimer's in the past.

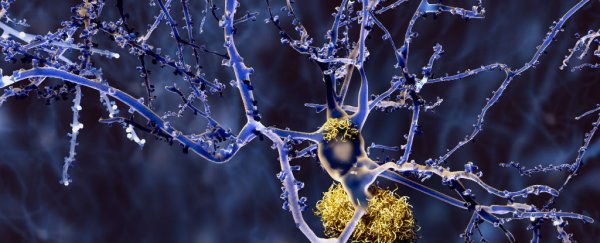

While the drug did nothing to combat symptoms that had already appeared, such as the appearance of dense clusters of beta-amyloid molecules - a sticky type of protein that clumps together and forms toxic plaques between neurons - when given to worms that were yet to develop symptoms, it appeared to block this process altogether.

"We showed that these worms that were doomed to develop Alzheimer's disease could be rescued," one of the team, Michele Vendruscolo, told Alan Yuhas at The Guardian.

When investigating the activity of the drug at a molecular level, Vendruscolo and his colleagues figured out that it stops the first stages of a process called primary nucleation, which occurs when naturally occurring proteins 'misfold' themselves and clump together with other proteins to form thin filament-like structures called amyloid fibrils, and smaller protein clusters called oligomers.

The build-up of these malfunctioning, clumping proteins is thought to seriously damage nerve cells in the brain and lead to the cognitive degeneration of Alzheimer's disease and dementia.

"The body has a variety of natural defences to protect itself against neurodegeneration, but as we age, these defences become progressively impaired and can get overwhelmed," Vendruscolo explains in a press release. "By understanding how these natural defences work, we might be able to support them by designing drugs that behave in similar ways."

While we can't jump to any conclusions just yet, because we're far from knowing if similar results will be seen in humans, the study points to new way of potentially fighting Alzheimer's disease.

This is not the first time bexarotene has been used in Alzheimer's research: earlier studies of bexarotene have suggested that the drug could actually reverse Alzheimer's symptoms by clearing protein clumps in the brain, but the results have more recently been all but debunked. What this study, published in Science Advances, has shown, is that the drug is ineffective in clearing protein clumps, but could play a role in stopping them from forming in the first place.

So rather than figuring out how to destroy toxic protein build-up once it appears in the brain (which has seen very little progress, despite countless studies trying to find a promising drug candidate) the study suggests that we should be looking at ways to proactively prevent this build-up from appearing at all.

"We know that the accumulation of amyloid is a hallmark feature of Alzheimer's and that drugs to halt this build-up could help protect nerve cells from damage and death," said Rosa Sancho, head of research at Alzheimer's Research UK, who was not involved in the study.

"A recent clinical trial of bexarotene in people with Alzheimer's was not successful, but this new work in worms suggests the drug may need to be given very early in the disease. We will now need to see whether this new preventative approach could halt the earliest biological events in Alzheimer's and keep damage at bay in in further animal and human studies."