Gastric bypass surgery is the most effective way for those with morbid obesity to lose weight, but new research has confirmed that there could be more to the procedure's success than just limiting food intake.

It seems the bypass also swaps the ecosystem of microbes in the digestive system for one that increases weight-loss, posing a potential way to achieve bypass's benefits without its risks. Best of all, this new assortment of gut bugs sticks around, helping patients lose weight long after the surgery.

In 2008, researchers from Arizona State University found the types of bacteria in the digestive systems of patients after they'd had a form of bariatric (weight-loss) surgery called a Roux-en-Y gastric bypass had changed dramatically, leading them to wonder if these new microbes might be at least partially responsible for ongoing weight loss.

With a tiny sample size of just three study groups containing three individuals each, it was hard to draw any solid conclusions.

So this time the researchers expanded their population and included patients who had also undergone another form of bariatric surgery called laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding (lap-band surgery).

The scientists analysed the diversity of microbial genomes as well as their waste products in 24 people who had undergone a gastric bypass procedure.

They then compared the results with samples taken from 14 patients who had lap-band surgery, 15 obese pre-surgery patients, and 10 patients within a healthy weight range.

As previously found, the researchers saw the microbes living in the guts of those who had their digestive tract rerouted were distinct from those of obese patients prior to surgery.

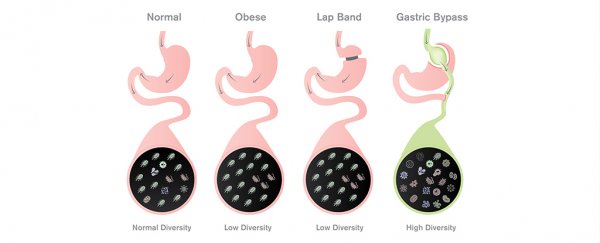

They also showed that the diversity of microorganisms was vastly higher post-surgery. Typically, the diversity of microbes decreases with an increase in weight.

"Diversity is good because of what we call functional redundancy," says Rosa Krajmalnik Brown from the Biodesign Institute at Arizona State University.

They also showed the microbes were also different to not only people within a healthy weight range, but to those who had lap-band surgery as well.

"This is one of the first studies to show that anatomically different surgeries with different success rates have different microbiome and microbiome-related outcomes," says lead researcher Zehra Esra Ilhan.

On one hand, this should come as no real surprise. Roux-en Y gastric bypass surgery is no simple procedure – a part of the stomach is stitched closed, making a small pouch for swallowed food to move into.

The small intestine is then attached to this new, smaller stomach, allowing the semi-digested food to jump past parts of the digestive tract which would have absorbed a lot of its calories.

Such a major restructure creates some fundamental changes to the acidity, nutrient, and oxygen levels inside the stomach and intestines – it would be shocking if at least some species bacteria didn't die off as new ones settled in.

By comparison, lap-band surgery doesn't reroute the food, but instead reduces the rate of consumption by creating a bottle-neck around the top of the stomach through a small incision near the belly-button.

Both procedures appeared to alter the microbial ecosystems in the gut, but the changes in diversity and weight loss were far more extensive in those who had the bypass surgery.

"One of the things we observe from the literature is that the oral microbiome community composition is very similar to the colon microbiome composition after bariatric surgery," says Ilhan.

One of those 'mouth' bacteria that started to show up at the other end of the gut belongs to a genus called Lactobacillus, an organism which has been associated with weight loss.

Gastric-bypass surgery is the most effective way for people to lose weight, but it is far from risk free. While deaths resulting from the surgery are rare, complications arising from the 'dumping' of barely digested food into the small intestine can include anything from nausea to malnutrition.

Permanently inheriting a new assortment of microbes that helps maintain weight loss would be great if it was even a small added benefit, though there's reason to suspect it might be significantly responsible on its own.

If so, for some people a simple microbial transplant might make the risks, pain, and complications of gastric bypass redundant.

A study published in 2013 transplanted microbes from post-gastric bypass mice into obese mice. The study saw the obese mice lost on average 29 percent of their excess weight. And kept it off.

Keeping in mind that this hasn't been replicated yet in humans, a future step for researchers could be to identify probiotics or diets that encourage the right kinds of microbes to grow to promote weight loss.

"Another positive outcome would be if we can find a microbial biomarker that will identify the best candidates for surgery and sustained weight loss," said Ilhan.

Once again, our gut's microscopic denizens are proving themselves to be one of the most important organs in our bodies. So remember to look after your tiny tenants.

This research was published in the International Society for Microbial Ecology Journal.