Carnivorous plants are known for being brutal and opportunistic predators, but an unexpected and fascinating discovery in Canada has proved especially gruesome.

Described as a "WTF moment" by researchers, it appears that pitcher plants in the wetlands of Ontario are not just luring in insects and spiders. They are also regularly capturing and devouring vertebrates.

These bogs belong to Canada's oldest provincial park, a place where plants and amphibians have been extensively researched. Never mind the generations of visiting naturalists, it was actually an undergraduate student on a field ecology course who first noticed what no one else had documented.

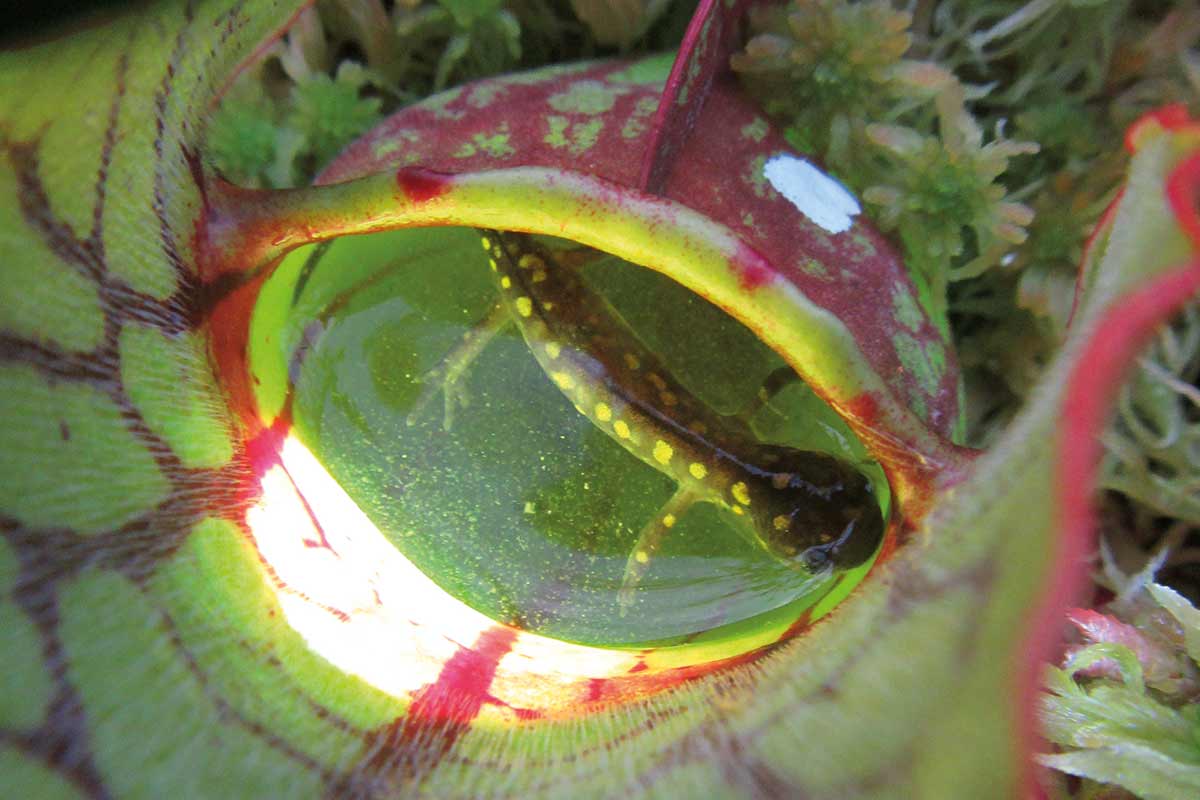

Upon looking into a purple pitcher plant (Sarracenia purpurea purpurea L.) in 2017, Teskey Baldwin discovered a trapped baby salamander.

While there are many examples of carnivorous plants trapping small vertebrates, such as rats and small birds, these are usually from the Tropics and not from northern pitcher plants despite "a wealth of study" on this particular plant family.

To figure out whether this was just one particularly unlucky salamander, researchers at the University of Guelph and the University of Toronto checked hundreds of plants during four different surveys at a single pond in these wetlands.

"In total," the authors write, "eight individual salamanders were found trapped in pitcher plants during survey efforts in 2017 and an additional 35 individuals were recorded with increasing survey effort in 2018."

The results suggest that vertebrate prey can occur with striking frequency in northern pitcher plants. The third and fourth survey, for instance, revealed that nearly 20 percent of surveyed plants had captured baby spotted salamanders.

These spotted salamanders (Ambystoma maculatum) are black with bright yellow dots, and the babies are around the size of a human finger.

The timing seemed to be linked up with the birth of new salamanders during "pulses of emergence" in the late summer and early fall. Several times, the researchers found more than one salamander captured in a single pitcher.

What happens after being trapped is quite grisly. In as little as three days, some salamanders went from alert and active in the fluid to completely dead, potentially from acidity, heat stress, starvation or infection. For others, their last breath was taken as many as 19 days later.

The salamander corpse is then broken down and decomposed by the plant's digestive enzymes and any other organisms that live in the leaf's water. Once the animal has died, the process is usually completed within ten days or less, and the speed of this is probably why we haven't noticed this particular prey for so long.

Sometimes, the authors add, the decomposition can also cause an icky stench.

While it's still not clear how these vertebrates end up in the sticky situation, the authors have a few ideas. Because they found so many salamanders, they think these could be more than just random accidents.

One hypothesis says the salamanders may regularly fall in because they're trying to catch the insects that the pitcher plant usually feeds on. Another idea, which the authors deem less likely, suggests the animals get stuck in the pitchers while trying to hide from predators.

"When plants were approached or disturbed, most salamanders rapidly swam to the bottom of the pitcher and tightly wedged themselves out-of-sight in the narrow, tapered stem of the pitcher," the authors describe.

"Individuals often remain submerged for several minutes and repeatedly dive to the pitcher bottom as long as the perceived threat remained."

(Patrick D. Moldowan)

(Patrick D. Moldowan)

Whatever the reason, the pitcher plant is sure to make use of the crucial nitrogen source. The authors estimate that "a single salamander could contribute to the plant an amount of nitrogen equivalent to that contained in three pitchers."

In a nutrient-poor environment, the amphibious meal is too good to pass up.

The research was published in The Scientific Naturalist.