Nearly five years on, the damaged Fukushima nuclear plant in Japan continues to leak small amounts of radiation into the Pacific Ocean, and more of that material is now showing up on the west coast of the US, according to new data.

Researchers have detected 110 new contaminated sites off the American Pacific coast, including the highest levels of radioactive contamination around 2,500 km west of San Francisco. That's still 500 times below US government safety limits for drinking water, so there's no need to panic even if you've recently been swimming or fishing in the Pacific. But it's an interesting insight into how nuclear waste spreads, and where the currents that govern our oceans have been moving.

"These new data are important for two reasons," said lead researcher Ken Buesseler from the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. "First, despite the fact that the levels of contamination off our shores remain well below government-established safety limits for human health or to marine life, the changing values underscore the need to more closely monitor contamination levels across the Pacific."

"Second, these long-lived radioisotopes will serve as markers for years to come for scientists studying ocean currents and mixing in coastal and offshore waters," he added.

Researchers have been continually monitoring the waters throughout the Pacific since the 9.0 magnitude earthquake caused the Fukushima nuclear plant to experience full meltdown in March 2011, on the look-out for radiation levels that may pose a risk to human health or the environment.

To date, the levels detected have remained well below the safe limit, and sampling of fish in British Columbia on the west coast of Canada hasn't shown any traces of Fukushima contamination, so there's no need for concern. But more radioactive material does seem to be appearing on the US Pacific coast.

So how do scientists know if radiation in the water has come specifically from Fukushima? Pretty much all seawater sampled from the Pacific will contain traces of an isotope called cesium-137, which has 30-year half-life and is left over from nuclear weapons testing carried out between the 1950s and '70s.

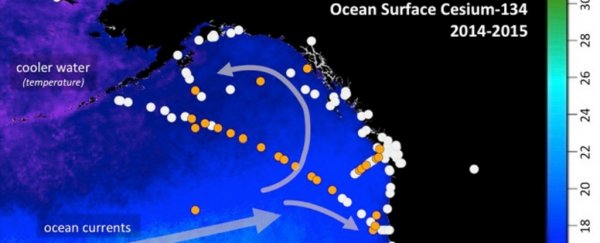

But Fukushima has its own unique isotope, cesium-134, which is like a 'fingerprint' of the Fukushima meltdown. With only a two-year half-life, it decays a lot quick than cesium-137, but it can still be detected in small amounts throughout the ocean, showing scientists exactly where the reactors radioactive material has spread.

Out of the 110 new contaminated samples detected off the US west coast, the most radioactive was collected around 2,500 km off the coast of San Francisco. It contained 11 Becquerel's per cubic metre of seawater – which is equivalent to 50 percent higher cesium levels than other samples collected in this part of the ocean so far.

Buesseler's research has also shown that Fukushima is still leaking radioactive material into the ocean in Japan, with the levels off the Japanese coast between 10 to 100 times higher than the levels off the US West Coast today.

"Levels today off Japan are thousands of times lower than during the peak releases in 2011," said Buesseler. "That said, finding values that are still elevated off Fukushima confirms that there is continued release from the plant."

The team will continue to monitor these radiation levels throughout the Pacific, with the hopes of better understanding these types of disasters so we can more efficiently mitigate their effects in the future. They'll present their latest results next week at the American Geophysical Union conference in San Francisco.

And for anyone still freaking out about radiation levels, let Veritasium put things into perspective for you. Because even the exclusion zones of Chernobyl and Fukushima aren't as radioactive as the inside of a smoker's lungs… seriously.