A team of scientists from New Zealand's Antarctic Research Centre, led by Dr Nick Golledge, have reconstructed Antarctica's ice sheet evolution over the past 25,000 years. The results have now been used to create the most accurate model to date on how rapidly the continent will melt.

It's already common knowledge that the West Antarctic ice sheet is in irreversible collapse and sea level rise is unavoidable, but scientists still understand very little about how Antarctica as a continent will respond to climate change in the future.

It's something we need to figure out, and fast, because Antarctica's ice sheets are likely to be the dominant driver of sea level rise in the future, and 10 percent of the global population is living less than 10 metres above sea level.

To do this, we need to look to the past. In order to accurately map how the ice sheets in Antarctica have shifted over tens of thousands of years, Dr Duanne White, a scientist from the Institute for Applied Ecology at the University of Canberra, is using a technique known as cosmogenic dating to analyse how long its been since rocks and sediment that were once covered in ice.

Cosmogenic dating involves analysing the amount of isotopes found in the rocks and sediment to figure out how long they'd been exposed to the cosmic radiation after the ice receded.

"I can map where the ice sheet has been in the field and then date when the ice was in that position," explained White in a press release. "We can then compare that evidence to past local climate information to get a sense of how that impacted the ice melting."

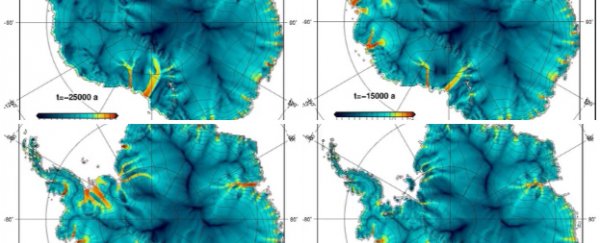

This data, along with other research findings, were used by Golledge's team to create a model that mapped what happened from the end of the last Ice Age, 25,000 years ago, to the present day, which you can see below.

Simulation of Antarctic Sheet evolution over the last 25,000 years by Dr Nick Golledge's research team at the Antarctic Research Centre, University of Wellington, New Zealand. Courtesy of Nature Communications

Simulation of Antarctic Sheet evolution over the last 25,000 years by Dr Nick Golledge's research team at the Antarctic Research Centre, University of Wellington, New Zealand. Courtesy of Nature Communications

The study showed that when the ice sheets begin to melt, it causes the ocean around Antarctica to become layered, or stratified, and the warm water at the bottom of these layers causes the ice sheet to melt even faster. This happened around 14,000 years ago, with the model suggesting Antarctica produced a global sea level rise of nearly three metres over just a few centuries.

The results were verified by White's data and published in Nature Communications in September.

Current oceanographic observations around Antarctica show that the ocean is once again becoming more layered, so we could see the ice sheet begin to collapse more quickly than we previously have.

"Twenty years ago we couldn't understand what drove the change we saw in the ice sheet in the past," said White. "But this new model is one of the first that can go back and reliably predict what happened in the past. That means it's more accurate at making projections for the future too."

White is now working with the Antarctic Research Centre to publish research on how quickly we can expect to see sea levels rise in the coming years, and hope that policy makers will use their research to make changes to help mitigate climate change and protect coastal populations.

"The thing I'm working towards is understanding how quickly the ice sheet might collapse if we do warm the planet up 2 to 4 degrees Celsius," said White.

"For example, recent evidence from the Pliocene, which was the last time we saw temperatures similar to what we're expecting in the future, indicates Antarctica lost enough ice to raise sea levels by 5 to 10 metres. Looking at more recent events will help us understand whether ice sheet collapse of this scale can happen in just a few centuries, or if it will take many thousand years" he explained.

"What's happened in the past isn't always a direct guide of what will happen in the future. But if we input that data into climate models, we can make informed projections based on previous behaviour," said White.

Love the environment? Find out more about opportunities to change the world with your research at the Institute for Applied Ecology at the University of Canberra.

Source: Institute for Applied Ecology at the University of Canberra, Nature Communications