Some of the most spectacular pictures of deep space are of nebulae - gorgeously coloured clouds of dust and gas glowing from within. They look peaceful and serene, but in actuality, they're scenes of violence.

Usually, nebulae are either the lingering ghosts of exploded stars, or stellar nurseries - regions where stars are being born at a furious rate.

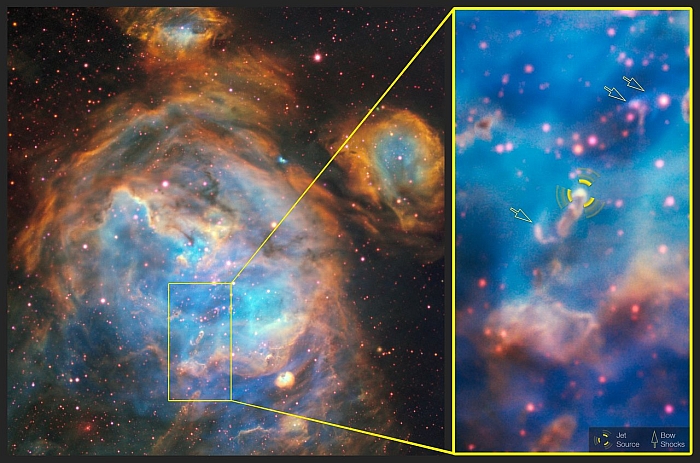

Such a stellar nursery is what features in a new European Southern Observatory photo of the Large Magellanic Cloud, one of the Milky Way's satellite galaxies. The nebula pictured is called N 180B, roughly 160,000 light-years away; tucked away in its folds and crannies, new stars are being born.

Like pretty much most things in space, the term 'nebula' is a category that includes several sub-types. N 180B is what is known as an emission nebula, because of how it produces light.

Unlike reflection nebulae, which reflect the light of nearby stars, and dark nebulae, which produce no light, the gas of emission nebulae emits optical light. But they can't do it alone. First, the gas needs to be ionised, or excited.

There are several kinds of gas that can do this, but in the case of N 180B, it's primarily atomic hydrogen. Ultraviolet radiation from the incredibly bright new stars - this nebula contains some of the brightest known clusters - ionises the atomic hydrogen, exciting it to a high-energy state.

As it gradually returns to its normal, lower-energy state, it releases the excess energy as photons - visible light.

Powerful stellar winds and radiation pressure from those newborn stars then blow the hydrogen away, carving out cavities, or bubbles, in the nebula. This has the effect of limiting the growth of the star, since they're literally pushing material away.

(ESO, A McLeod et al.)

(ESO, A McLeod et al.)

Five of these bubbles can be seen in the photo: one big one in the middle, with four smaller ones around it.

That stellar wind can also trigger further star formation. As this gas collides with and compresses into surrounding gas, it can grow dense enough to trigger the gravitational collapse that will start a new cluster of baby stars.

Yeah. Space is pretty awesome. But something makes this picture, captured by the MUSE instrument on the Very Large Telescope, even more awesome: it shows in detail the parsec-scale jets being spewed from the poles of a massive young star.

It's called HH 1177, and its discovery was published in February of last year (HH stands for Herbig-Haro, the name given to turbulent regions in nebulae associated with young stars).

It's not just any old protostellar jet. It was the first such jet detected in visible wavelengths outside the Milky Way. And at around 10 parsecs (32.6 light-years) in length, it's also the longest protostellar jet astronomers have found to date.

(ESO, A McLeod et al.)

(ESO, A McLeod et al.)

And it can provide some clues about star formation. We can see, for example, that the jets are highly focused, or collimated; they're not spreading out much over distance. This likely means they're being produced by the magnetohydrodynamics of the star's accretion disc, and can help astronomers understand the accretion process.

We also know that the Large Magellanic Cloud has relatively low metal content. Since metals were only propagated throughout the Universe after a few generations of stars forged them and spewed them out when they died, HH 1177 can help understand how low metallicity affects star formation - hopefully leading to insights about star formation in the early Universe.

That's a lot to pack into one photo! But isn't it glorious? Don't you just want to go there and see it with your own eyes? Ah, well… we can dream.

If you want to download a wallpaper-sized version of the photo to fuel your own daydreams, you can grab it on the European Southern Observatory website here.