Africa was once populated by huge, unique dinosaur species. But scientists know very little about what they were like, what happened to them, and how they're related to the dinosaurs found across Asia.

That's why a spectacular new find in Egypt has palaeontologists buzzing.

In Egypt's Sahara Desert, an expedition with the Mansoura University Vertebrate Paleontology (MUVP) initiative has unearthed a bus-sized sauropod, the family of dinosaurs that includes the biggest behemoths to ever walk on land such as Brachiosaurus and Diplodocus.

They've called the newly discovered creature Mansourasaurus shahinae, and are studying it to help fill in the blanks left by the region's lack of fossils.

"Mansourasaurus shahinae is a key new dinosaur species, and a critical discovery for Egyptian and African palaeontology," said researcher Eric Gorscak, a postdoctoral research scientist at The Field Museum.

"Africa remains a giant question mark in terms of land-dwelling animals at the end of the Age of Dinosaurs. Mansourasaurus helps us address long standing questions about Africa's fossil record and palaeobiology - what animals were living there, and to what other species were these animals most closely related?"

(Andrew McAfee, Carnegie Museum of Natural History)

(Andrew McAfee, Carnegie Museum of Natural History)

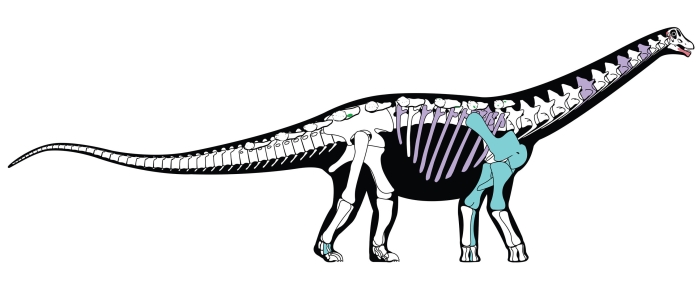

Mansourasaurus lived about 80 million years ago, and the fossilised individual measured around 8 to 10 metres (26 to 33 feet) - around the length of a London bus - and weighed about as much as an African bull elephant.

The fossil evidence suggests it was a long-necked herbivore with bony plates embedded in its skin.

Africa's fossil record is so sparse because many remains from the Late Cretaceous (the period between around 100 to 66 million years ago) are concealed beneath vegetation-covered land - not the exposed rock that's famous for turning up fossils.

That's why this discovery is so exciting. The Mansourasaurus's bones were exceptionally well preserved, with parts of the skull, lower jaw, neck and back vertebrae, ribs, most of the shoulder and forelimb, part of the hind foot, and pieces of dermal plates surviving.

"When I first saw pics of the fossils, my jaw hit the floor," said researcher Matt Lamanna of the Carnegie Museum of Natural History.

"This was the Holy Grail - a well-preserved dinosaur from the end of the Age of Dinosaurs in Africa - that we paleontologists had been searching for for a long, long time."

The individual belongs to the group of sauropods known as Titanosaurs, which includes some truly gargantuan beasts. Patagotitan, for instance, measuring 37 metres (121 feet) in length, and the comparably sized Argentinosaurus.

Mansourasaurus was pretty titchy in comparison, but it had other secrets trapped inside its bones.

(Andrew McAfee, Carnegie Museum of Natural History)

(Andrew McAfee, Carnegie Museum of Natural History)

During the Late Cretaceous, Earth looked pretty different from how it looks now. It was during the Cretaceous that the continents, until that point joined into a supercontinent called Pangaea, began splitting apart, and the planet went through some dramatic geological changes.

Fossil records of both flora and fauna are brilliant for piecing together how the continents were joined. And this is where Mansourasaurus shines.

Lead researcher Hesham Sallam of the Department of Geology at Mansoura University and his team analysed the bones, and concluded that the dinosaur was more closely related to sauropods from Europe and Asia than those from South America, and even South Africa.

This proves, the researchers said, that at least some dinosaurs could still move between Europe and Africa in the Late Cretaceous.

There's more work to be done. Now that one dinosaur has been found, others may be out there.

The Mansoura University Vertebrate Paleontology group will continue its work looking for fossils in northern Africa.

"What's exciting is that our team is just getting started," Sallam said.

"Now that we have a group of well-trained vertebrate paleontologists here in Egypt, with easy access to important fossil sites, we expect the pace of discovery to accelerate in the years to come."

The research has been published in the journal Nature Ecology & Evolution.