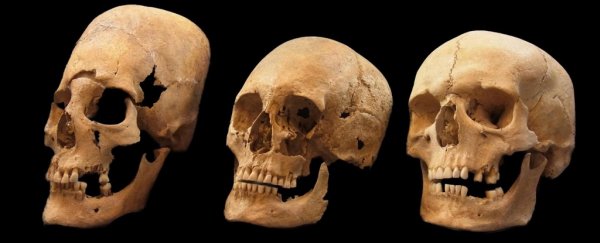

For 1,500 years, they lay buried among the relics of medieval Germany: the remains of women irreconcilably different to the skeletons around them, courtesy of their towering, elongated skulls.

In fact, the legacy of artificial cranial deformation across human history is so abnormal and 'other' it's sometimes presented as evidence of extra-terrestrial life. A new genetic analysis reveals otherwise – but also sheds light on cultural practices so distant and forgotten, they're almost alien.

If not for their misshapen skulls these otherwise unremarkable skeletons – discovered by researchers in Bavaria during the 20th century – might never have been noticed by scientists.

"Archaeologically, they are not that different from the rest of the population," geneticist Joachim Burger from the University of Mainz explained to National Geographic.

"Genetically, they are totally different."

(State Collection for Anthropology and Palaeoanatomy Munich)

(State Collection for Anthropology and Palaeoanatomy Munich)

Burger and fellow researchers sequenced the genomes of almost 40 individuals buried in south Germany, dating from the late 5th to early 6th century.

Of these, nine were women showing clear signs of skull deformation, while five others bore the marks of 'intermediate' elongation. The remaining individuals showed no signs of the practice.

Even though they lived and died alongside the ancient Bavarians who had blue eyes and blonde hair, the genes revealed that these women with deformed skulls came from somewhere else entirely.

"Our data points to Barbarian tribes in Western and Central Europe specifically acquiring exotic looking women with elongated heads born elsewhere," explains genomicist Krishna Veeramah from Stony Brook University in a press release.

In particular, the genomes provide a match for southeastern Europe – specifically Bulgaria and Romania – meaning these women would have likely had darker hair and darker eyes than their Bavarian associates, not to mention their expansive, receding foreheads.

(State Collection for Anthropology and Palaeoanatomy Munich)

(State Collection for Anthropology and Palaeoanatomy Munich)

That's what the genetic analysis can tell us about these long-ago people. But how did these women end up in medieval Bavaria, and why were their heads warped like this?

The team speculates the women had their supple heads bound as infants in order to produce the distinctive, elongated look – a cultural practice carried out in other parts of the world over the course of history, including elsewhere in Europe and Asia.

As for how they ended up buried in Bavaria, the researchers suggest it's likely the women with elongated skulls came from wealthy or distinguished families in southeastern Europe, and may have been betrothed to men in local Bavarian communities to help form political or strategic alliances in the region.

If the hypothesis is correct, it could tell us more than just where these women and their elongated skulls came from – expanding what we know about history in this part of the world back then.

"Nobody thought that marriage and kinship had a really important function in the period," historical archaeologist Susanne Hakenbeck from the University of Cambridge in the UK, who wasn't involved with the study, told National Geographic.

Not everybody accepts the hypothesis, and it will take a lot more research to say for sure if the mystery of these elongated skulls can actually be explained by a bevy of brides traded to barbarians in Bavaria.

As for the lives these women led, with their towering, alien-like heads, betrothed to unfamiliar men in a land far from home? We may never know the details – but hopefully they were good lives, not marred by their 'privileged' deformity.

"There is a discussion going on whether the artificial cranial deformation causes cognitive deficiencies," one of the team, osteologist Michaela Harbeck from the Bavarian State Collection for Anthropology and Palaeoanatomy explained to Haaretz.

"Some studies suggest there were several pathological conditions associated with it, including bulging eyes – but this highly depends on the degree of the deformation. I would guess that our individuals, which had only medium deformed skulls, did not suffer from it."

The findings are reported in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.