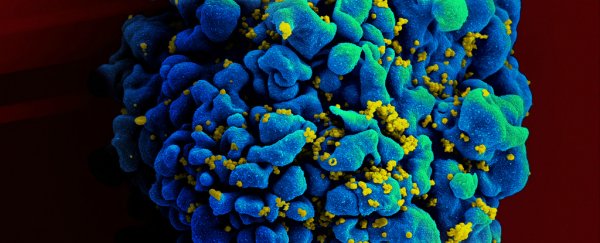

The first human trial of a new generation of potential HIV drugs, known as 'broadly neutralising antibodies', has been conducted, and so far the results are looking really promising. Researchers from Rockefeller University in the US have found that a single dose of the antibody can trigger an incredible 300-fold reduction in the amount of virus present in infected patient's blood.

Although antibodies have been used to fight HIV in the past, the virus always ends up mutating to evade the immune cells. But this antibody, called 3BNC117, has the ability to fight a range of viral strains - and the Phase 1 clinical trial results suggest that broadly neutralising antibodies could offer new hope for treatments, and even a vaccine, for HIV.

"What's special about these antibodies is that they have activity against over 80 percent of HIV strains and they are extremely potent," says Marina Caskey, one of the study's leaders, in a press release.

The antibodies naturally occur in the immune system of 10 to 30 percent of people with HIV, but usually only appear after several years of being infected with the virus - by which stage HIV has typically managed to evolve to escape them. But the researchers managed to isolate and clone the 3BNC117 antibodies, turning them into a potential treatment.

In the trial, the team gave 29 uninfected and HIV-infected volunteers one of four different intravenous doses of the antibody and monitored them for 28 days. Publishing in Nature, the researchers report that the highest strength dose caused up to an incredible 300-fold drop in HIV levels within just a week of treatment.

3BNC117 works by targeting the CD4 binding site that HIV uses to attach to host cells. This stops the virus from hiding and triggers a patient's own immune system to naturally get rid of it. But the researchers also believe that the antibody might be able to kill viruses hiding in infected cells, which current antiretroviral drugs can't target.

The biggest concern was how quickly the virus would mutate to evade the antibody, so the team continued to monitor the participants for a further 28 days after the initial trial period. During this time, the HIV virus managed to surge back to normal levels in some patients, while in others it remained suppressed beyond the end of the trial.

"One antibody alone, like one drug alone, will not be sufficient to suppress viral load for a long time because resistance will arise," said Caskey in the release. But even if ongoing monthly doses of antibodies are required, this will still be less intensive than the daily cocktail of drugs currently taken by people with HIV, she adds.

But the really exciting part of the research is that the team is now also looking into ways they can trigger an uninfected person's immune system to generate these broadly neutralising antibodies - effectively paving the way for a vaccine against HIV.

Further research is now needed to work out whether broadly neutralising antibodies have potential as an ongoing HIV treatment, but these early results are definitely worth getting excited about.