A new blood test could offer an early warning sign to breast cancer patients that the disease has returned after surgery and chemotherapy treatments. Capable of detecting tumour DNA circulating in the patient's blood, the test successfully identified signs of relapse in 12 out of 15 patients, an average of 7.9 months before visible signs of the cancer appeared.

"Ours is the first study to show that these blood tests could be used to predict relapse," lead researcher Nicholas Turner from the Institute of Cancer Research in London told the press. "It will be some years before the test could potentially be available in hospitals, but we hope to bring this date closer by conducting much larger clinical trials starting next year."

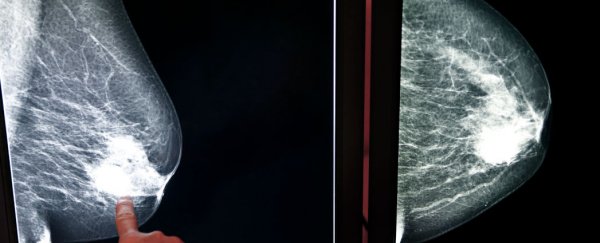

According to the World Health Organisation (WHO), breast cancer is the most common cancer in women both in the developed and less developed world. With a 1 in 36 chance that it will be responsible for a patient's death, it's the second most common cause of cancer death in women, surpassed only by lung cancer. The highest risk of recurrence is during the first two years after treatment.

Turner and his team worked with 55 woman who had been diagnosed with early-stage, localised breast cancer. Each of them were treated with either surgery, chemotherapy, or both, and the researchers followed their progress for the next two years, giving them the blood test once every six months or until they had a relapse.

Fifteen of the women ended up relapsing, and the blood test detected the tumour DNA in 12 of them. "The other three patients all had cancers that had spread to the brain where the protective blood-brain barrier could have stopped the fragments of the cancer entering the bloodstream," James Gallagher reports for BBC News. "The test detected cancerous DNA in one patient who has not relapsed."

The researchers also found that the women who tested positive for the tumour DNA after treatment were 12 times more likely to relapse than those who tested negative. The test also helped the team to better track the mutations that remain accumulate, grow, and spread through the body after breast cancer treatment.

"We are moving into an era of personalised medicine for cancer patients. This test could help us stay a step ahead of cancer by monitoring the way it is changing and picking treatments that exploit the weakness of the particular tumour," Paul Workman, chief executive of the UK Institute of Cancer Research, told the press. "Studies like this also give us a better understanding of how cancer changes to evade treatments - knowledge we can use when we are designing the new cancer drugs of the future."

The results of the trial have been published in Science Translational Medicine.

A non-invasive, relatively cheap test like this is definitely a promising prospect, but there are a couple of big caveats. Firstly, the sample size wasn't huge, and the results of the test were inconsistent. Secondly, cancer researchers Tilak Sundaresan and Daniel Haber from Harvard University in the US, who weren't involved in the research, wrote in an accompanying journal article that it's not yet clear if early detection can be used to start treatment early and stop new tumours from forming.

"Recurrent forms of breast cancer are 'rarely curable', however, so it's unclear whether or not detecting the early signs of a relapse would actually offer a chance for a cure, they write. That's something that scientists will need to work out in future studies," Arielle Duhaime-Ross says at The Verge.

"That is unknown from this research and we hope to address it in future studies," Turner told the BBC. "[But] we're really talking about a principle that could potentially be applied to any cancer that has gone through initial treatment for which there's a risk of relapse in the future."