Researchers have developed an electronics heat shield just 10 atoms thick, a shield that has the potential to make our gadgets both safer to use and more compact in the future.

Heat and electronics don't mix well, which is why you might find your laptop shutting down in protest if you use it in the sunshine at the beach, and why Samsung had to recall its 2016 Galaxy Note phone because of an overheating battery problem.

It's also why every laptop, phone and other electronics device you use comes with built-in cooling mechanisms - but those mechanisms can add significant bulk. That's where this new material comes in, as the researchers say it works at the nanoscale level.

"We're looking at the heat in electronic devices in an entirely new way," says electrical engineer Eric Pop, from Stanford University in California.

Part of that "new way" is to consider heat as sound: the streams of electrons that produce electricity collide with the atoms in the materials they pass through, creating a mass of miniature vibrations. We feel it as heat, but it's also a cacophony of sound, at frequencies too high for the human ear to detect.

The team also borrowed a trick from many homes – where windows use two layers of glass rather than one to muffle sound and block the flow of heat. The same multi-layer idea is used in the new 10-atom heat shield.

"We adapted that idea by creating an insulator that used several layers of atomically thin materials instead of a thick mass of glass," says electrical engineer Sam Vaziri, from Stanford University.

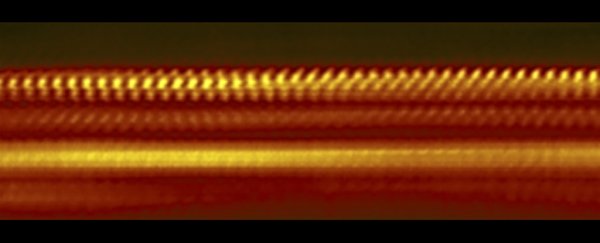

Scientists have been working with materials just a few atoms thick for the last fifteen years. In this study, the materials graphene, molybdenum diselenide, molybdenum disulfide and tungsten diselenide were used to build a four-layered sandwich measuring just 10 atoms from top to bottom – about 50,000 thinner than a sheet of paper.

In the same way that layers of glass might deaden the sound from a recording studio, so these layers can deaden the electron vibrations that manifest themselves as heat. The gaps mean energy is lost, even though they're very thin, and the end result is a cooling layer that takes up a microscopic amount of space.

There's still plenty of work to do before this approach can be applied to the gadgets we use every day, and the researchers are now looking for ways in which their protective layering could be applied to electronic components during the manufacturing process.

Further down the line, the team says, there could be potential for controlling vibrational energy inside materials in the same way that electricity and light can be handled, at the smallest possible scales.

"As engineers, we know quite a lot about how to control electricity, and we're getting better with light, but we're just starting to understand how to manipulate the high-frequency sound that manifests itself as heat at the atomic scale," says Pop.

The research has been published in Science Advances.