Researchers have identified a new link between Alzheimer's and a protein called tau that could help treat the disease in the future.

The research centres on a variation of a gene called ApoE4 which increases the risk of Alzheimer's by up to 12 times – but scientists still aren't sure exactly how it increases that risk.

Previous work has focused on the ApoE4 gene variant and increased levels of the amyloid beta protein, one of the prime suspects for causing Alzheimer's. However, the team behind the new study says how ApoE4 affects the tau protein might be just as important in figuring out how the disease develops.

"Once tau accumulates, the brain degenerates," says senior researcher David Holtzman, from the Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis.

"What we found was that when ApoE is there, it amplifies the toxic function of tau, which means that if we can reduce ApoE levels we may be able to stop the disease process."

ApoE (or Apolipoprotein E) helps to move cholesterol around the body. In rare cases, people can be born without the ApoE gene, leading to very high cholesterol levels and associated health problems.

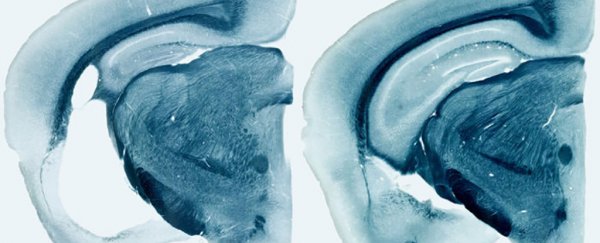

To take a closer look at how ApoE could be linked to Alzheimer's and other brain diseases, researchers studied mice given variants of the ApoE gene: ApoE2, ApoE3, and ApoE4. Some mice lacked the gene altogether.

In the absence of the ApoE proteins produced by these genes, especially the ApoE4 variant, tangled clumps of the tau protein were much less harmful to brain cells, so reducing the influence of ApoE could be a promising avenue for future research into treatments.

The ApoE4 protein seems to be responsible for turning on other genes that ramp up the body's immune system reaction to tau, in this case causing extra damage.

In further tests, the researchers grew immune cells from the brains of the mice with ApoE4 alongside neurons containing human tau: the immune cells launched an inflammatory response that seemed to wage war on the neurons.

"ApoE4 seems to be causing more damage than the other variants because it is instigating a much higher inflammatory response, and it is likely the inflammation that is causing injury," says Holtzman.

"But all forms of ApoE – even ApoE2 – are harmful to some extent when tau is aggregating and accumulating. The best thing seems to be in this setting to have no ApoE at all in the brain."

In follow-up tests, the researchers looked at the autopsies of 79 people who'd died from tauopathies other than Alzheimer's – the class of diseases associated with the build-up of tau protein tangles.

They found that at the time of death, those people with the ApoE4 gene variant had more brain damage than those without.

In short, cutting down on ApoE levels in the brain might slow or block the process of neurodegeneration, even after tau tangles or amyloid beta plaques have started to form, and that's an exciting development in tackling these challenging diseases.

Whereas attempts have been made to deal with both amyloid beta and tau protein build-ups in the brain, no one has yet tried targeting ApoE, which could effectively limit the damage of both the other proteins simultaneously.

"Assuming that our findings are replicated by others, I think that reducing ApoE in the brain in people who are in the earliest stages of disease could prevent further neurodegeneration," says Holtzman.

The research has been published in Nature.