The Vinland Map, once thought to be one of the earliest depictions of North America after its discovery by Europeans, has gone from being famous to being infamous: It turns out that the map is a complete fake.

That's the verdict of researchers who analyzed the ink on the map and found that it comes from the 1920s. This isn't quite the groundbreaking 15th-century work of cartography that it was originally claimed to be, but rather a deliberate forgery.

While major doubts had previously been raised about the authenticity of the Vinland Map, the X-ray fluorescence spectroscopy (XRF) and field emission scanning electron microscopy (FE-SEM) techniques used here to assess the chemicals in the ink represent the most thorough look at the document yet.

A macro X-ray fluorescence spectroscopy analysis of the map. (Yale University)

A macro X-ray fluorescence spectroscopy analysis of the map. (Yale University)

"The Vinland Map is a fake," says Raymond Clemens, the curator of early books and manuscripts at the Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library at Yale University, where the map is stored. "There is no reasonable doubt here. This new analysis should put the matter to rest."

While carbon dating puts the map parchment at around 600 years old, the ink contains high levels of titanium and smaller amounts of barium – elements you would expect to find in the earliest commercially produced titanium-white pigments of the 1920s.

Anatase, a form of titanium dioxide used during the same period, can be found all across the map. There's none of the iron gall ink that medieval scribes are known to have written with, ink which is made up of iron sulphate, powdered gall nuts, and a binder substance.

The researchers were also able to compare the Vinland Map with manuscripts that really are from the 15th century, finding much lower levels of titanium and much higher levels of iron in the ink used there.

The chemical breakdown of the inscription on the back of the map. (Yale University)

The chemical breakdown of the inscription on the back of the map. (Yale University)

On the back of the map is an inscription that links it to the Speculum Historiale, part of an encyclopedia written in the Middle Ages. This is probably where the parchment for the forgery came from, and the new analysis reveals that the original Latin inscription has been overwritten with titanium ink – signs of a deliberate forgery.

"The altered inscription certainly seems like an attempt to make people believe the map was created at the same time as the Speculum Historiale," says Clemens. "It's powerful evidence that this is a forgery, not an innocent creation by a third party that was co-opted by someone else, although it doesn't tell us who perpetrated the deception."

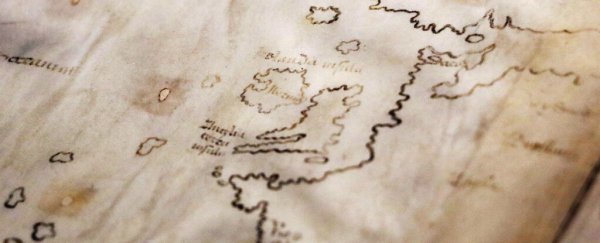

First offered to museums in 1957 alongside a short medieval text, the Vinland Map shows the so-called 'Vinlanda Insula', part of North America's coastline to the southwest of Greenland. It was first thought to back up the idea that Vikings had reached the continent (and mapped it) long before Christopher Columbus.

While the Norse colonization of North America is now largely accepted, this map is not evidence of it – as we know from the length of time spent analyzing the document as well as the comparisons to other historical works that have actually been verified.

The researchers say the new analysis shows how the latest equipment and scanning techniques can help get definitive answers on which historical documents are genuine and which aren't, enabling us to focus our time on the former.

"Objects like the Vinland Map soak up a lot of intellectual air space," says Clemens. "We don't want this to continue to be a controversy. There are so many fun and fascinating things that we ought to be examining that can actually tell us something about exploration and travel in the medieval world."