The world we occupy today is very different from the one occupied by our not-so-distant ancestors. As we enter a new geological epoch – the Anthropocene, in which the human footprint has left its mark – there is much concern about global deforestation, melting ice sheets and general biosphere degradation.

But another, often overlooked, casualty of this new epoch is the diversity of microorganisms (including bacteria, viruses and fungi) that live on and in us.

If our microbiome – the genetic diversity of these organisms – is a canary in the microbial coal mine, then my work with East African hunter-gatherers suggests that it is hanging upside down on its perch. ![]()

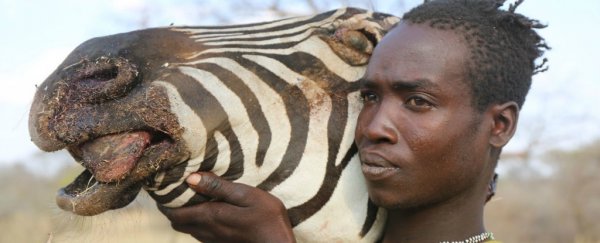

In the field I have watched a Hadza hunter skilfully butcher a baboon and share meat with others around a fire. Nothing goes to waste. Organs, including the brain, are consumed along with raw colon and stomach.

By sterile Western standards, it is a gruesome sight for an evening meal.

No matter how many times I watch Hadza carve up animals dispatched with a bow and arrow, I am always taken aback by the extraordinary exchange of microbes between this group and their environment. A microbial tango that probably characterised the entirety of human evolution.

Why is this important? Recent research has shown that disease is often associated with a fall in microbial diversity. What we don't know is which way cause and effect runs.

Does disease cause a drop in microbial diversity or does a drop in diversity cause – or precede – disease?

It's still early days and a lot of work lies ahead. However, the idea that the microbes, and the diversity of microbes, that we carry may help us better understand and head off disease has spawned a level of optimism in medical research not seen since the introduction of antibiotics over 50 years ago.

Which brings me back to the Hadza.

Living and working among the Hadza makes me think of the intimate relationship humans have probably evolved with diverse groups of microbes. With each animal killed, microbes are given the opportunity to move from one species to the next.

With each berry that is plucked from a bush or tuber dug from beneath the microbial-rich ground, each and every act of foraging keeps the Hadza connected to an extensive regional (microbial) species pool.

It is their persistent exposure to this rich pool of microorganisms that has endowed the Hadza with an extraordinary diversity of microbes; much greater than we see among people in the so-called developed world.

Ecology with gut feeling

Viewed through the lens of ecology, the less diverse gut microbiome in the West can potentially be seen as either a result of a degraded regional species pool (all species available to colonise a local site) or an increase of environmental filters (things that thwart or limit the movement of microbes in the environment, or alter their composition).

A combination of both is probably at play.

Much attention has been focused on environmental filters, such as diet, as the primary culprit for decreasing microbial diversity in the Western gut.

Another environmental filter is the overuse of antibiotics. Each course of antibiotics can reduce the diversity of microbes in the host.

Other filters may include too much time spent indoors, an increase in caesarean births and a decrease in breastfeeding rates, antimicrobial products such as handgels, small doses of antibiotics in the meat we eat, and modern hygiene.

But the contribution of the regional species pool gets little attention in microbial research. I suspect it has something to do with the difficulties in such large-scale sampling and, of course, cost and priorities.

Given that regional species pools - though focused on macroorganisms (organisms large enough to see with the naked eye) - is a central theme in ecology, it would be beneficial if it was incorporated into more human-microbe research.

Considering our classic environmental filtering example of antibiotics, one wonders if someone who took an antibiotic and experienced a reduction in microbial diversity would not recover more quickly - to their pre-antibiotic state of microbial diversity - if he or she had exposure to a robust and diverse regional species pool, once the course of antibiotics was completed.

Surely more attention and better management of environmental filters would pay dividends in improving microbial diversity in humans.

However, having a better understanding of how ecological degradation may be hitting a little closer to home (our own gut) than most of us previously imagined may provide the much-needed impetus that this generation needs to finally put the health of ecosystems, large and small, into perspective.

Importantly, all the buzz around the microbiome may be an opportune moment to mobilise a much-needed group of micro-environmentalists to better teach how to appreciate the importance of what's happening to our shared biosphere.

Jeff Leach, Visiting Research Fellow, King's College London.

This article was originally published by The Conversation. Read the original article.