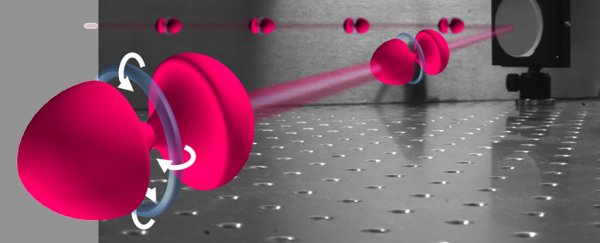

Physicists have just discovered a unique property in laser light: it's capable of producing its own swirls of energy that look a whole lot like smoke rings.

These doughnut-shaped circles of optical energy - now officially called spatiotemporal optical vortices, or STOVs for short - travel with the laser light and control the flow of energy around it.

Not only could these 'smoke rings' help explain phenomena that have baffled laser scientists for years, they could also open up new ways for lasers to be used everywhere from microscopes to high-speed internet connections, according to a new study.

"Lasers have been researched for decades, but it turns out that STOVs were under our noses the whole time," said the senior author of the study, Howard Milchberg from the University of Maryland.

"This is a robust, spontaneous feature that's always there. This phenomenon underlies so much that's been done in our field for the past 30-some years."

Given the right conditions, laser beams can 'self-focus' and become more intense as they travel, unlike regular light, which typically expands in size as it goes. It's these self-focusing types of beams that the researchers have been analysing.

The light energy carried by the laser is controlled by the STOVs, flowing through the inside of the ring, and then looping back around the outside (you can see this visualised in the image at the top of the article).

What makes them even more useful for scientists is they travel with the beam itself.

"The smoke ring vortices we discovered may have even broader applications than previously known optical vortices, because they are time dynamic, meaning that they move along with the beam instead of remaining stationary," explained one of the team, Nihal Jhajj.

"This means that the rings may be useful for manipulating particles moving near the speed of light."

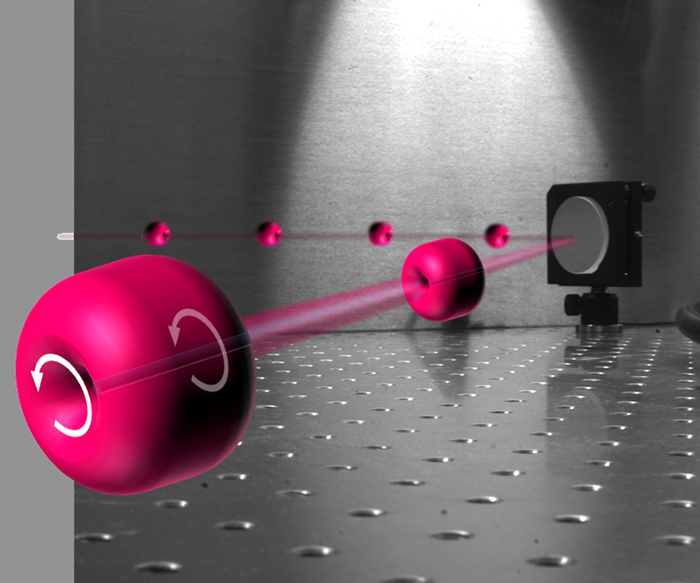

Another type of vortex - the orbital angular momentum (OAM) vortex - has been used to help improve microscopy and telecommunications since the 1990s, and could see use in computing, too.

You can see these visualised below:

OAM vortices, unlike the STOVs shown at the top of the page, rotate around a central beam. Credit: Howard Milchberg

OAM vortices, unlike the STOVs shown at the top of the page, rotate around a central beam. Credit: Howard Milchberg

Unlike OAM vortices, the STOVs now give scientists a different kind of structure to work with.

The team compares the laser smoke rings to a kind of 'electrified angel's halo', with energy shooting back and forth between the halo and the angel's head.

"A STOV is not just a spectator to the laser beam, like an angel's halo," explained Milchberg, noting how STOVs can control the central beam's shape and energy flow.

"It is more like an electrified angel's halo, with energy shooting back and forth between the halo and the angel's head. We're all very excited to see where this discovery will take us in the future."

Right now, Milchberg and Jhajj can only talk in broad terms about the potential uses for STOVs, because we've only just discovered them, and much more research is required to understand how they operate.

But considering they can control the central beam's shape and energy flow, there's the potential to use them in everything from advanced microscopy technology to new optical computers.

The study has been published in Physical Review X.