Every new fossil find is a chance to learn more about the creatures of the past, but the discovery of a fossil of a pregnant sea creature has proved to be more illuminating than most – the embryo it carried wasn't inside an egg.

Now researchers think the fish-eating Dinocephalosaurus reptile, which swam in the oceans around 245 million years ago, gave birth to live babies rather than laying eggs, as was previously thought.

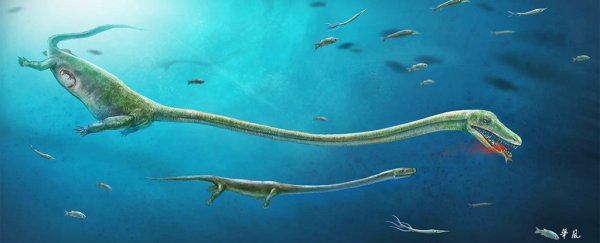

A relative of dinosaurs, as well as a distant ancestor to birds and crocodiles, Dinocephalosaurus had a long, slender neck - think along the lines of the Loch Ness Monster - and could grow up to around 4 metres (or 13 feet) in length.

According to researchers from China, the US, the UK, and Australia, this is the first vertebrate from a large group called archosauromorpha that has been found to be viviparous – able to give birth to live young, as mammals do.

"It's great to see such an important step forward in our understanding of the evolution of a major group coming from a chance fossil find in a Chinese field," says one of the researchers, Mike Benton from the University of Bristol in the UK.

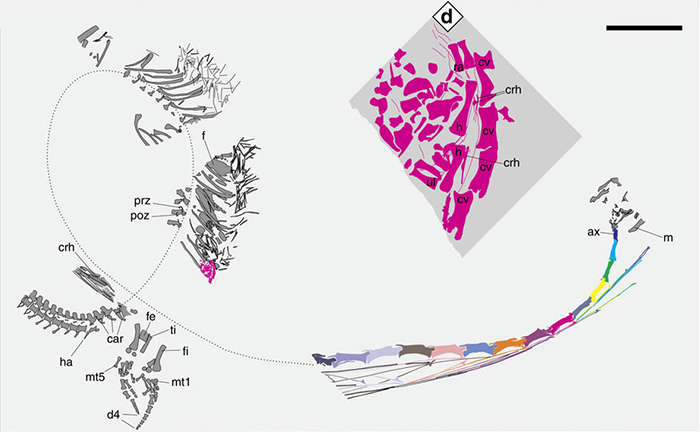

The embryo was facing forward towards the mother's head, suggesting it was indeed a baby Dinocephalosaurus and not something the mother had just eaten, which would have been digested head first.

It was also found in a curled posture that's typical for vertebrate embryos, and no egg shells were found in or around the skeleton.

Drawing showing the position of the embryo, in bright pink. Credit: Jun Lui et al.

Drawing showing the position of the embryo, in bright pink. Credit: Jun Lui et al.

While the embryo inside the fossil was small – around half a metre (1.6 feet) in size – it showed the tell-tale signs of being a Dinocephalosaurus, including elongated ribs and a long neck.

The researchers told BBC News they can't rule out the possibility that an egg shell was originally in place, but it seems unlikely. They also said the findings could open the way to more detailed analysis of other fossils in the search for further embryos.

There are thousands of species in the archosauromorpha group, which includes crocodiles and birds, and all are thought to lay eggs.

Scientists had thought there was some biological reason preventing these vertebrates from giving birth to live young, but now it seems vertebrates of this type could indeed evolve to be viviparous.

The researchers made another discovery too – the Dinocephalosaurus apparently determined the sex of its babies through allocation of chromosomes, rather than through the temperature of the nest, as modern-day descendants like turtles and crocodiles do.

The reptile would have swum in the South China seas during the Middle Triassic period, and being able to give birth to live offspring would certainly have helped the creature avoid predators, as it could stay out at sea without needing to return to land to lay eggs.

Some reptiles have evolved to give birth to live young today, but this find is remarkable because of its age and the type of species involved.

"Our discovery pushes back evidence of reproductive biology in the clade by roughly 50 million years," write the researchers, "and shows that there is no fundamental reason that archosauromorphs could not achieve live birth."

The findings have been published in Nature Communications.