Scientists have used a mice model to reverse some of the most severe damage done to the brain by dementia - and they did this with a surprisingly old medication typically used for asthma.

The discovery could open up the road for treatments that could restore memory and spatial impairment in people with conditions like Alzheimer's. While a human treatment is still some way off, the research shows one method we could use to retroactively treat the buildup of tau proteins, long thought to be a key factor in dementia.

Key to the improvement was an asthma drug called zileuton (or Zyflo) that's been in use for 22 years. The team from Temple University in Philadelphia is highly optimistic, claiming that their findings could eventually improve the lives of millions of people with dementia.

"We show that we can intervene after disease is established and pharmacologically rescue mice that have tau-induced memory deficits," says senior investigator Domenico Praticò.

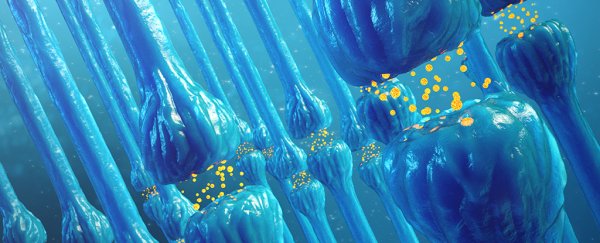

There's still plenty we don't know about diseases like Alzheimer's, but the evidence points to tangles of tau proteins blocking connections between neurons. Another protein, amyloid precursor protein (APP), is also thought to be involved.

In this study the scientists targeted inflammatory molecules called leukotrienes. Having found that leukotrienes cause damage to nerve cells as dementia develops, the team wanted to try blocking the formation of these molecules.

That's where zileuton came in. It was given to one group of mice engineered to have similar dementia problems to 60-year-old humans with the condition, while another group of mice were given placebos instead.

After 16 weeks, treated mice were performing much better on maze tests than mice who hadn't received zileuton. The treated group was also found to have 90 percent fewer leukotrienes in their brains, and 50 percent fewer tau tangles.

"It's really dramatic what we observed," Praticò told Stacey Burling at The Inquirer. "For the first time, we are showing that we can do something after the disease is established."

In fact, the synapses of the mice given zileuton looked as healthy as normal mice after close analysis. It's almost as if this aspect of the dementia had been completely cleared up.

Before we get too excited, there are some limitations to consider. For example, these mice didn't have any beta-amyloid plaque build ups (caused by APP) in their brains, which are consistently found alongside tau plaques in human brains with dementia.

And while mice are often used in research for their genetic and biological similarity to humans, transferring treatments over from these animals can be difficult. Add to that the limits of our understanding about dementia, and there's still a lot of work to be done.

Nevertheless, the fact that researchers were able to actually reverse some of the damage of dementia after it had taken hold is cause for celebration, because the condition isn't usually diagnosed in humans until the effects have already started.

Another reason for optimism is that zileuton has already been approved as a safe drug, albeit with advisory warnings and potential side effects. But it should make it easier to set up a clinical trial, which the team of scientists wants to do next.

"This is an old drug for a new disease," says Praticò. "The research could soon be translated to the clinic, to human patients with Alzheimer's disease."

The research has been published in Molecular Neurobiology.