New research suggests that Alzheimer's disease is actually triggered by the brain trying to fight off invading microbes, such as bacteria or viruses. While the process isn't yet fully understood, it appears that infecting pathogens crossing the blood-brain barrier could cause the build-up of sticky plaques associated with the brain condition.

So far, this hypothesis has only been tested on mice, but if the same thing is found to be happening in humans, it could help improve scientists' understanding of Alzheimer's, and eventually lead the way for more effective treatments in the future.

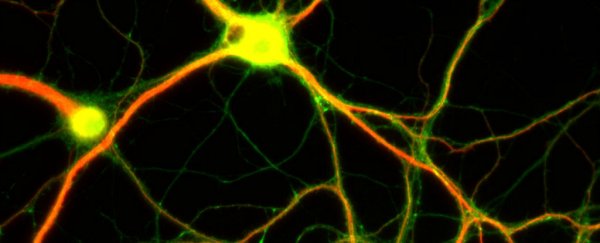

As Anil Ananthaswamy reports in New Scientist, sticky plaques of beta-amyloid proteins - which come from the fatty membranes outside nerve cells - have long been associated with Alzheimer's disease, though researchers still don't have much solid evidence on why they accumulate and what they do. All they know is when someone has Alzheimer's, they normally have plaque build-up too.

It's thought that these sticky clumps might be a natural response to infection that block cell-to-cell signalling and activate an immune response that triggers inflammation and eats disabled cells - potentially causing the memory-loss and confusion associated with Alzheimer's.

To test this, a group of researchers from Harvard Medical School inserted bacteria into the brains of mice, and found that plaques developed overnight.

They then tested this on roundworms and cultured neuronal cells, which confirmed the same thing - when the brain became threatened by pathogens, plaque builds up.

While we still don't quite know what's going on, the researchers suggest it's possible that beta-amyloid is being used to trap and kill bacteria, viruses, or other types of pathogens that make it through the blood-brain barrier - which is a biological 'fence' protecting the brain.

If these protein plaque cages aren't then cleared away quickly enough, it's possible that they could be causing inflammation and other protein tangles, leading to Alzheimer's.

"Our findings raise the intriguing possibility that Alzheimer's pathology may arise when the brain perceives itself to be under attack from invading pathogens, although further study will be required to determine whether or not a bona fide infection is involved," said one of the team, neurologist Robert Moir. "It does appear likely that the inflammatory pathways of the innate immune system could be potential treatment targets."

The blood-brain barrier weakens as we get older, which also means there's a greater chance of unwanted bacteria or viruses getting through, and could explain why Alzheimer's becomes more common as we age.

The next step in the research is to examine the brains of people who've died from Alzheimer's to see if this new hypothesis holds up.

"It is obviously outside the box," neurologist David Holtzman of the Washington University School of Medicine, who wasn't involved in the research, told The New York Times. "It really is an innovative and novel study."

Previously, scientists had thought the build-up of these sticky plaques were simply a consequence of getting older, but it could turn out that they're actually trying to help us – even if they end up doing more harm than good.

The results have been published in Science Translational Medicine.