Researchers working on a more effective treatment for brain tumours have achieved such amazing results, they thought there was an error in their calculations. But the results are real: and the implications could be huge.

By using an organic 'nanocarrier' to deliver chemotherapy drugs directly to tumours in the brain, the scientists have been able to achieve significant improvements in the number of cancer cells being killed off.

The technique has so far only been tested in mice, but if replicated in humans - which, to be clear, is no easy feat - it could eventually lead to new treatments for people with specific types of brain cancer.

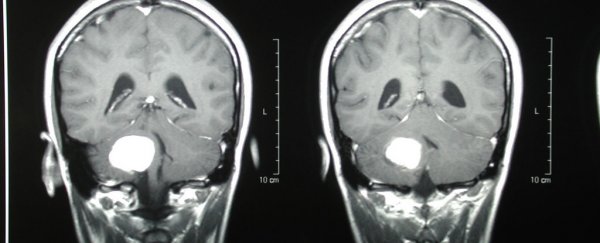

Lead researcher and radiologist Ann-Marie Broome at the Medical University of South Carolina has been targeting glioblastoma multiforme (GBM) - a particularly stubborn form of cancer that's currently incurable.

Its position in the brain makes it difficult to operate on, and the blood-brain barrier (designed to protect the brain from harm) means that getting an effective dose of drugs to the tumour isn't easy.

That's where this new nanotechnology approach comes in. Broome and her colleagues used what they already knew about GBM and platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF) - which regulates cell growth and division - to create their new nanocarrier, built from an aggregate of molecules.

The carrier, technically known as a micelle, is small enough to cross the brain-blood barrier to apply the treatment directly. The researchers describe it as using a postal code to get the drugs to the right place - the micelle gets the dose to the right street, and then the PDGF is used to find the right house.

"I was very surprised by how efficiently and well it worked once we got the nanocarrier to those cells," says Broome. "When we perfect this strategy, we will be able to deliver potent chemotherapies only to the area that needs them."

"This will dramatically improve our cure rates while cutting out a huge portion of our side effects from chemotherapy," she adds. "Imagine a world where a cancer diagnosis not only was not life-threatening, but also did not mean that you would be tired, nauseated, or lose your hair."

The brain tumour's own natural chemistry actually gives the micelle nanocarriers their potency. As the tumour grows, it creates waste by-products that cause acidity in the blood, which triggers the release of the micelle's payload.

"It's very important that the public recognise that nanotechnology is the future," said Broome. "It impacts so many different fields. It has a clear impact on cancer biology and potentially has an impact on cancers that are inaccessible, untreatable, undruggable - that in normal circumstances are ultimately a death knell."

Now that the researchers have shown that nanocarrier delivery is possible - at least in mice - they need to test a wider range of drugs against a wider range of cancers. If all goes well, hopefully we'll hear about clinical trials involving humans later on down the track.

There's obviously a ways to go before this technique will become available to treat cancer in people, but nanotechnology has been showing promising results in previous studies, so this might just be how we end up fighting the disease in the future.

The findings have been published in Nanomedicine.