The frosty vastness of Greenland might have eluded the far-reaching grasp of the Roman Empire, but that's not to say imperial fortunes were never felt by the icy lands up north.

A new study has provided a stunning, unprecedented glimpse into the peaks and valleys of ancient Roman and Greek civilisation by looking in a place so distant and removed from these long ago cultures, it's almost alien.

Deep inside the Greenland ice sheet, buried several hundred metres under the surface, trapped ice preserves an indelible record of old Rome and Greece that you won't find in the pages of any history book.

How? The answer is pollution.

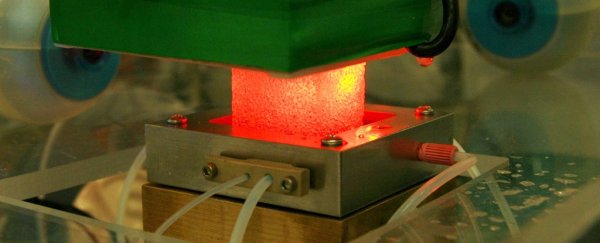

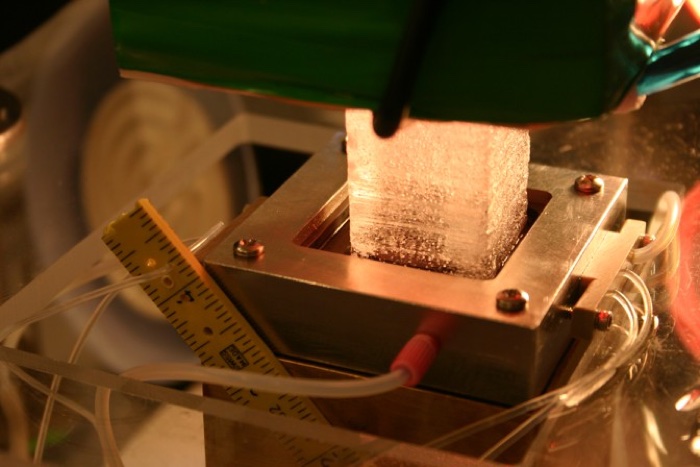

An ice core used in the research (PNAS)

An ice core used in the research (PNAS)

An international team led by researchers from Nevada's Desert Research Institute (DRI) analysed ice samples extracted by the North Greenland Ice Core Project (NGRIP), which began drilling ice cores under the frozen centre of Greenland in the late 1990s.

The cores they looked at range from very deep to even deeper – ice samples cut from between 159 to 580 metres (521 to 1,902 ft) underground. In essence, the deeper you go, the further back in time you're looking, over a period of almost two millennia.

Thousands of years ago, ancient Greek and Roman civilisations mined and smelted lead and silver ores – metal work that helped underpin the physical and economical foundations of their societies.

But then – as now – that industry came at a cost, in the form of lead pollution, which escaped into the atmosphere, drifting on the wind for thousands of kilometres.

Some of that wind breezed over Greenland, where it collided with snow falling onto the icy surface. As time passed, more and more snow fell, burying the lead-tainted ice below as the years and centuries passed.

But if you extract cores from that ice stack, like the researchers here have done, and analyse the amount of lead emissions in it, you can generate a granular year-by-year record of what industrial pollution looked like thousands of years ago.

In this case, the researchers' timeline gives us a view of between 1100 BCE to 800 CE, and we can use it as a proxy for how economically active or prosperous these ancient societies were, based entirely on the yardstick of smog.

"Our record of sub-annually resolved, accurately dated measurements in the ice core starts in 1100 BCE during the late Iron Age and extends through antiquity and late antiquity to the early Middle Ages in Europe – a period that included the rise and fall of the Greek and Roman civilisations," says one of the researchers, DRI hydrologist Joe McConnell.

"We found that lead pollution in Greenland very closely tracked known plagues, wars, social unrest, and imperial expansions during European antiquity."

As amazing as this kind of time-travelling science is, it's not the first time it's been attempted. A previous study used the same kind of technique in the mid–1990s, but with a major difference.

That study based its conclusions on just 18 ice data points. The new study expands that to over 21,000 discrete lead measurements, providing never-before-seen insights into ancient Greek and Roman economic activity, and helping trace its varying wars, plagues, famines, and peaks.

"I wouldn't say the lead pollution graph is a close reflection of GDP but it's probably the best overall proxy for economic health we've got," one of the team, archaeologist Andrew I. Wilson from the University of Oxford, told The New York Times.

The findings, revealed this week, show that while lead may be a toxic, non-valuable metal, its usage throughout history is actually an invaluable marker to scientists – and to historians too, who now have a new, uniquely precise timeline to work against.

"The paper speaks for itself," historian Seth Bernard, who wasn't involved with the research, told The Atlantic.

"It feels sort of like we've discovered the Americas. There was another continent over there, that was always there, that we can see now."

The findings are reported in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.