As far as supervolcanoes go, they don't get much bigger, or more talked about, than the one below Yellowstone National Park in the US. Ever since the disaster film 2012 picked the eruption of Yellowstone Caldera as the beginning of the end for life on Earth, we've been fascinated by exactly what's going on underneath that geothermal hot spot.

And now scientists have found that it's a whole lot more than we previously imagined. A team the University of Utah has just announced that they've found a second reservoir of hot, partly molten rock, lying 20-45 kilometres beneath the super volcano, and it's 4.4 times larger than the shallower magma chamber we already knew about.

Publishing their results in Science today, the team reports that the hot rock in this new chamber could fill the Grand Canyon up 11.2 times. So, er, no need to panic then, right guys?

The researchers stress that the threat of an eruption from the supervolcano hasn't changed at all (for those playing along at home, there's an annual one in 700,000 chance of Yellowstone erupting). The only thing that's new is that we've now been able to fully map the volcanic system, thanks to new imaging technology.

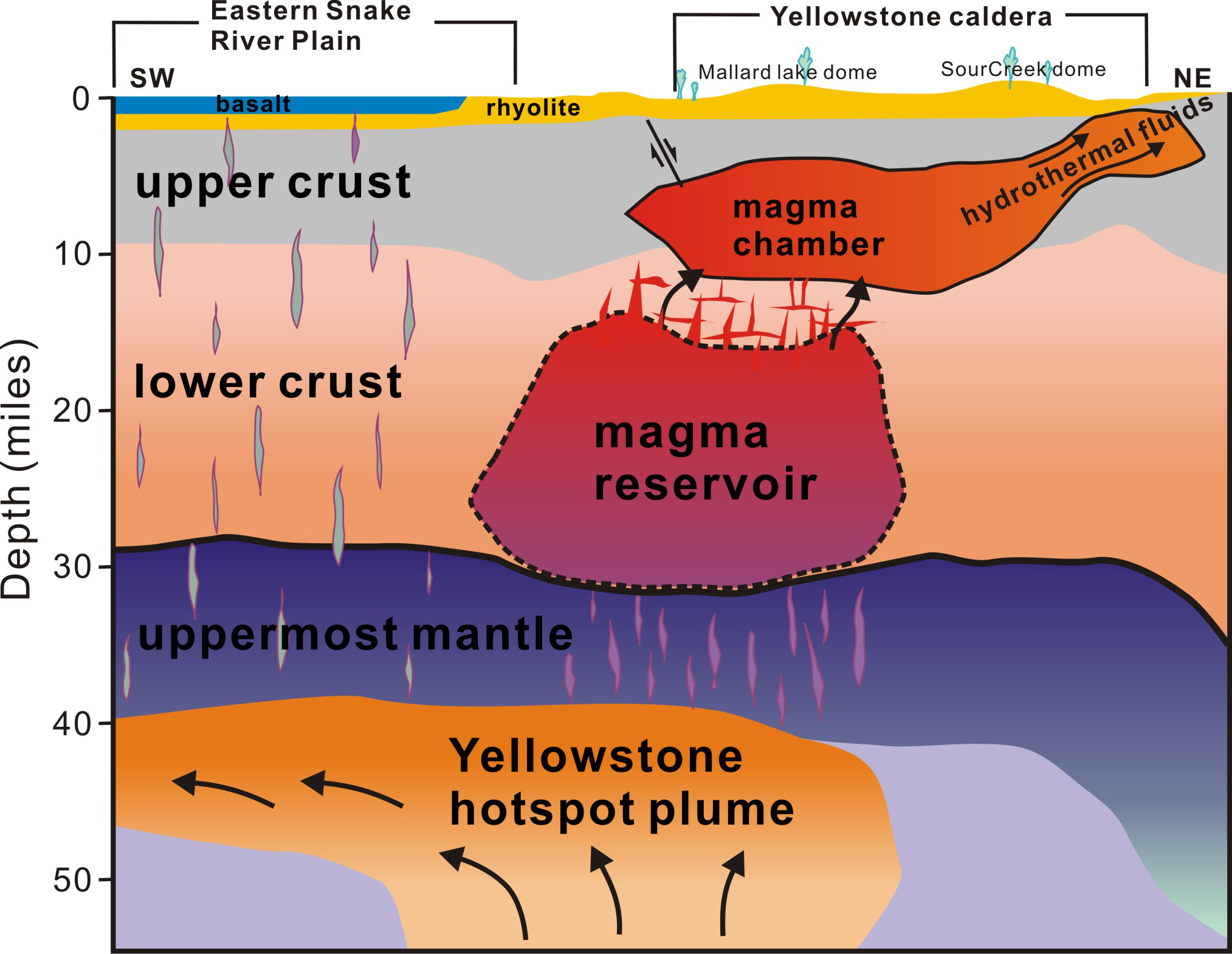

"For the first time, we have imaged the continuous volcanic plumbing system under Yellowstone," lead author Hsin-Hua Huang said in a press release. "That includes the upper crustal magma chamber we have seen previously plus a lower crustal magma reservoir that has never been imaged before and that connects the upper chamber to the Yellowstone hotspot plume below."

To do this, the team used a technique called seismic imaging, which works sort of like a medical CT scan, but it uses earthquake waves instead of X-rays to see what's going on beneath the surface. These earthquake waves move faster through cold rock, and slower through hot and molten rock.

And what they revealed was that there's a giant magma reservoir below the chamber we already knew about, which acts kind of like a giant holding pen. The researchers believe this newly discovered chamber sucks up hot rock from the top of the Yellowstone hot plume, which is about 64 kilometres below the Earth's surface, through a series of cracks in the Earth's crust, and then moves it up to the shallow magma chamber above.

Hsin-Hua Huang, University of Utah

Hsin-Hua Huang, University of Utah

This smaller top chamber is the one that's emptied when the supervolcano does erupt, something that's only happened three times in the past - 2 million, 1.2 million and 640,000 years ago - each time with catastrophic results.

The good news is that, contrary to popular perception, these giant chambers aren't filled to the brim with bubbling molten rock - the majority of the rock inside is solid or spongelike, with only a few pockets of molten rock. In the new chamber, it's estimated that as little as 2 percent is actually melted.

So that means it's only about one-quarter of a Grand Canyon worth of actual magma in there, says one of the team members, Jamie Farrell, in the release. No big deal. "The magma chamber and reservoir are not getting any bigger than they have been, it's just that we can see them better now using new techniques," he added.

The new research pieces together the gaps in our understanding of this complex volcanic system, and will also help us to better assess the risk of eruptions in the future.

And seeing as it's one of the largest super volcanoes on the planet, sitting on the most vigorous continental geothermal system we have, that's pretty important. Let's get this right, guys.