We should be grateful we have anuses. Some creatures don't have one, so they have to poop out of their mouths. But as it turns out, there's also an animal whose poop-chute appears only when it needs to defecate.

If you hate having to describe a typical day in your job, spare a thought for biologist Sidney Tamm from the Marine Biological Laboratory in Massachusetts, who spent a considerable amount of time filming warty comb jellies (Mnemiopsis leidyi) defecating.

Until now, it was believed these members of the phylum ctenophore – ancient jellyfish-like organisms – had a butt that was open for business 24/7. But Tamm is here to correct the textbooks with evidence of what seems to be a first of its kind: a disappearing, reappearing butthole.

"That is the really spectacular finding here," Tamm told New Scientist's Michael Le Page. "There is no documentation of a transient anus in any other animals that I know of."

The jellies gobble up tiny crustaceans and baby fish through an opening which, for the sake of simplicity, we can think of as a mouth with lips.

From there, the meal goes past a throat and down an oesophagus which grinds the food, and finally into a funnel-shaped stomach. Any bulky components that can't be digested are sent back up and out of the mouth, while the rest enters a branching network of canals that distribute nutrients around the body.

The final leg of the journey involves two canals each ending in a Y-shaped cul-de-sac. It was always assumed that there was some kind of opening in each of them for the pulped fish bits to be excreted. But no matter how hard Tamm looked, he couldn't find one.

"The anus is invisible between defecations," Tamm told Becky Ferreira at Motherboard. "You cannot see it either with your eyes or through a microscope."

Furthermore, it looks like the animals only use one of the two ends of the Y, some making use of the left, and others of the right canal. The other didn't form an anus, at least not in the ten days the creatures were observed.

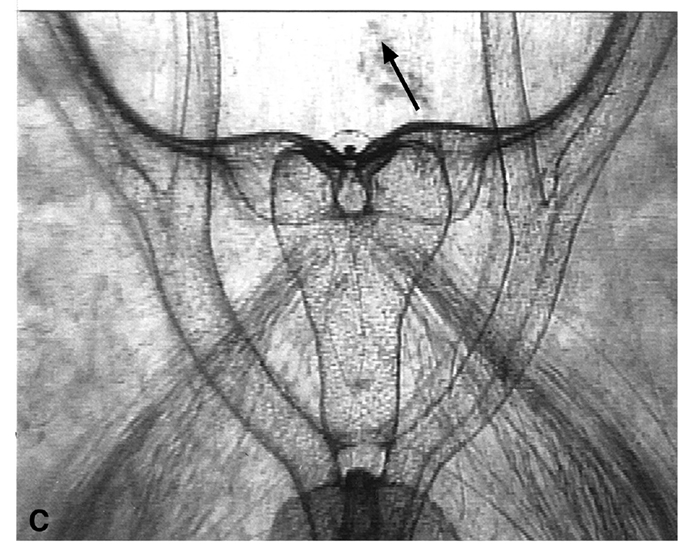

Tamm recorded the whole digestive process in warty comb jellies in a variety of life stages and analysed it step-by-step, measuring how each part of the system responded. He discovered as one of the canals swells with waste, it pushes to the outer edge of the comb jelly, until it bumps into its skin from the inside.

Then, at the last moment, the jelly essentially 'grows a butt' - the canal fuses with the jelly's outer skin to form an anal pore, which immediately seals back up again once the waste has burst forth.

He recorded the process a number of times, noting different pore sizes and timing. But the hole always vanished again, leaving no discernible trace.

But this discovery isn't just a bit of poop trivia - it could actually tell us something interesting about evolution.

Maybe NSFW? Warty comb jelly anus, plus poop. (Tamm, Invertebrate Biology, 2019)

Maybe NSFW? Warty comb jelly anus, plus poop. (Tamm, Invertebrate Biology, 2019)

As far as relatively complex animals go, ctenophores probably represent the oldest branch in the family tree. That makes them pretty handy organisms to study if we want to find some clues on how fundamental anatomical structures like mouths and buttholes first came about.

Yes, it's a serious evolutionary question. Why develop a back door when a single opening can do both jobs of taking food in, and getting rid of the waste?

While some animals with simple guts do indeed have a single entrance and exit point, Tamm's discovery could be the first example of a primitive animal with a dynamic opening.

There is, of course, the possibility that there is some sort of structure lurking there, yet to be identified. No doubt there's a whole line of hopefuls polishing their microscopes to verify or refute Tamm's work, adding much needed detail on comb jelly pooping.

But if the thin wall of tissue does indeed tear apart every time the jelly has to expel waste (which could be every ten minutes for the junior jellies!), then the mechanisms responsible could hint at an evolutionary stepping stone towards anuses in other animals. Including our own.

This research was published in Invertebrate Biology.