In November last year, geologists announced they'd picked up something really weird: a huge seismic event originating in the island of Mayotte in the Indian Ocean, felt all across the globe, source unknown. A few months later, scientists used modelling to produce an answer - hypothesising a giant underwater volcanic eruption.

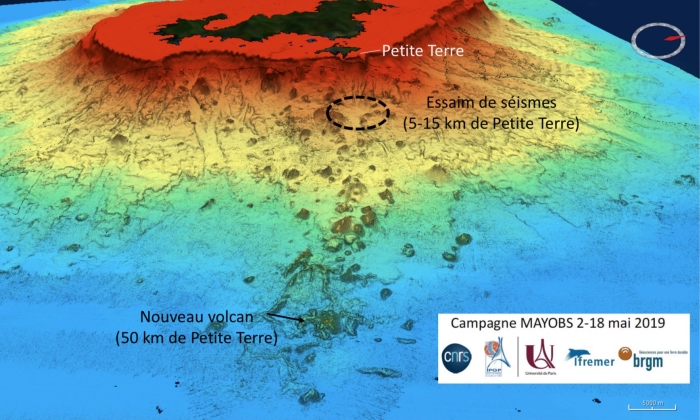

And now it seems that is pretty likely to be the case. Scientists travelled out to where they think the swarm's epicentre is located, and they found a large active volcano, rising 800 metres (2,624 feet) from the seafloor, and sprawling up to 5 kilometres (3.1 miles) across.

A large active volcano that wasn't there six months prior.

If these volcanic birth pains didn't produce the detected seismic activity, that would be a pretty amazing coincidence. But more research is still needed to make absolutely sure.

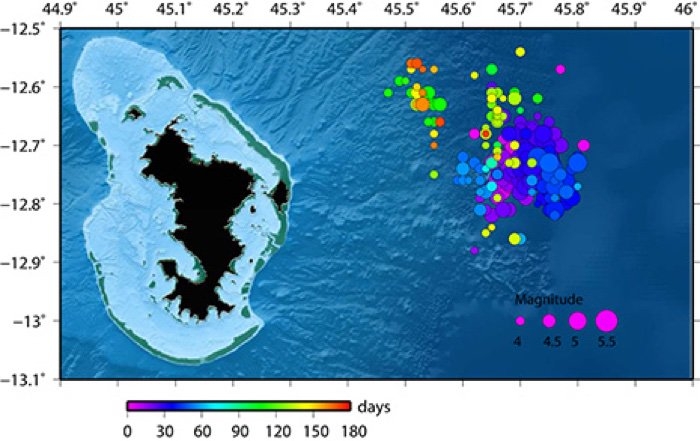

The seismic rumbles actually started on 10 May 2018. Just a few days later, on 15 May, a magnitude 5.8 quake struck. Since that time, hundreds of seismic rumbles have been detected, most on the smaller side, with the notable exception of the Earth-rattling low-frequency November event.

(BGRM)

(BGRM)

All those events pointed to a spot around 50 kilometres from the Eastern coast of Mayotte, a French territory and part of the volcanic Cormoros archipelago sandwiched between the Eastern coast of Africa and the Northern tip of Madagascar.

To find out what was going on, a number of French governmental institutes sent a bunch of scientists aboard the Marion Dufresne research vessel to investigate the area.

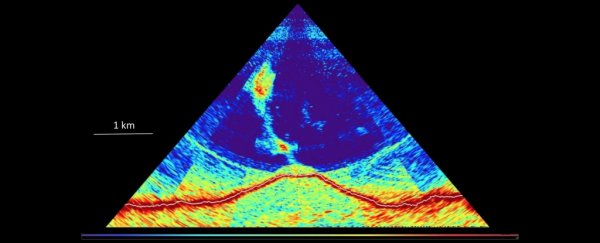

Starting in February, the team began monitoring the region. They placed seismometers on the seafloor, 3.5 kilometres deep, and used a multibeam sonar to map the seafloor. They dredged up rocks from far below.

The researchers combined this with data collected from Mayotte to build a comprehensive picture of what was occurring down in the dark depths of the lower bathypelagic.

(MAYOBS - CNRS/IPGP/IFREMER/BRGM)

(MAYOBS - CNRS/IPGP/IFREMER/BRGM)

It's a fascinating one. Data from the seismometers suggests the existence of a large magma chamber between 20 to 50 kilometres below the surface. This could have been seeping hot magma to the seafloor, where it met the cooler water and contracted, causing the crust to crack.

The plume of volcanic material produced only reached about 2 kilometres upwards, which explains why nothing was visible on the surface. The rocks pulled up from the seafloor were popping - a sign, according to Science, of high-pressure gas escaping from volcanic material.

But that's not all. GPS data from Mayotte has revealed that the island is both shifting and sinking. It's moved 10 centimetres eastward and sunk 13 centimetres since May of last year. This suggests the magma chamber that produced the volcano is collapsing and shrinking.

This could help explain how the volcano formed: it's consistent with a mantle plume formation, where a rising plume of hot rock in Earth's mantle creates melting at shallow depths. Cormoros is a mantle plume hotspot - the islands were formed by volcanic activity - but, again, this is yet to be confirmed by detailed study.

That research is currently underway.

Meanwhile, the French government is also taking steps to ensure the safety of the residents of Mayotte, where tremors and sinking continue.

"The government is fully mobilised to deepen and continue understanding this exceptional phenomenon and take the necessary measures to better characterise and prevent the risks it would represent," the French Ministry of the Interior wrote in a press release.

In the meantime, a mission to support civil safety and security has been dispatched to the island.