Researchers have developed an extremely cheap centrifuge made from paper, and it can easily be used in developing nations to rapidly test for diseases such as malaria.

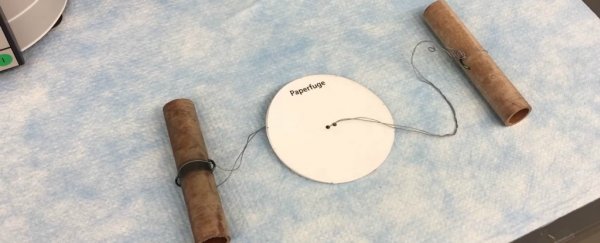

The device, dubbed the paperfuge, costs a mere US$0.20 to create, can be made with materials found in remote areas, and doesn't require any electricity to use, making it perfect for doctors in the field. All it requires is paper, a few simple materials such as string, and some elbow grease.

"In a global-health context, commercial centrifuges are expensive, bulky and electricity-powered, and thus constitute a critical bottleneck in the development of decentralised, battery-free point-of-care diagnostic devices," writes the team, led by Manu Prakash from Stanford University.

In case you're unfamiliar, a centrifuge is a device that can spin samples – such as vials of blood – to extreme speeds, separating the materials inside to make them easier to analyse. Because of this, centrifuges are an essential laboratory tool.

The problem is that traditional centrifuges are large, heavy, and expensive, and they require electricity to function, which pretty much ties them to hospital or laboratory settings. They're especially hard to get to people living in isolated communities, where tropical diseases are prevalent.

Without a hospital nearby, doctors aren't able to quickly and accurately analyse samples, putting these populations at a greater risk of going untreated.

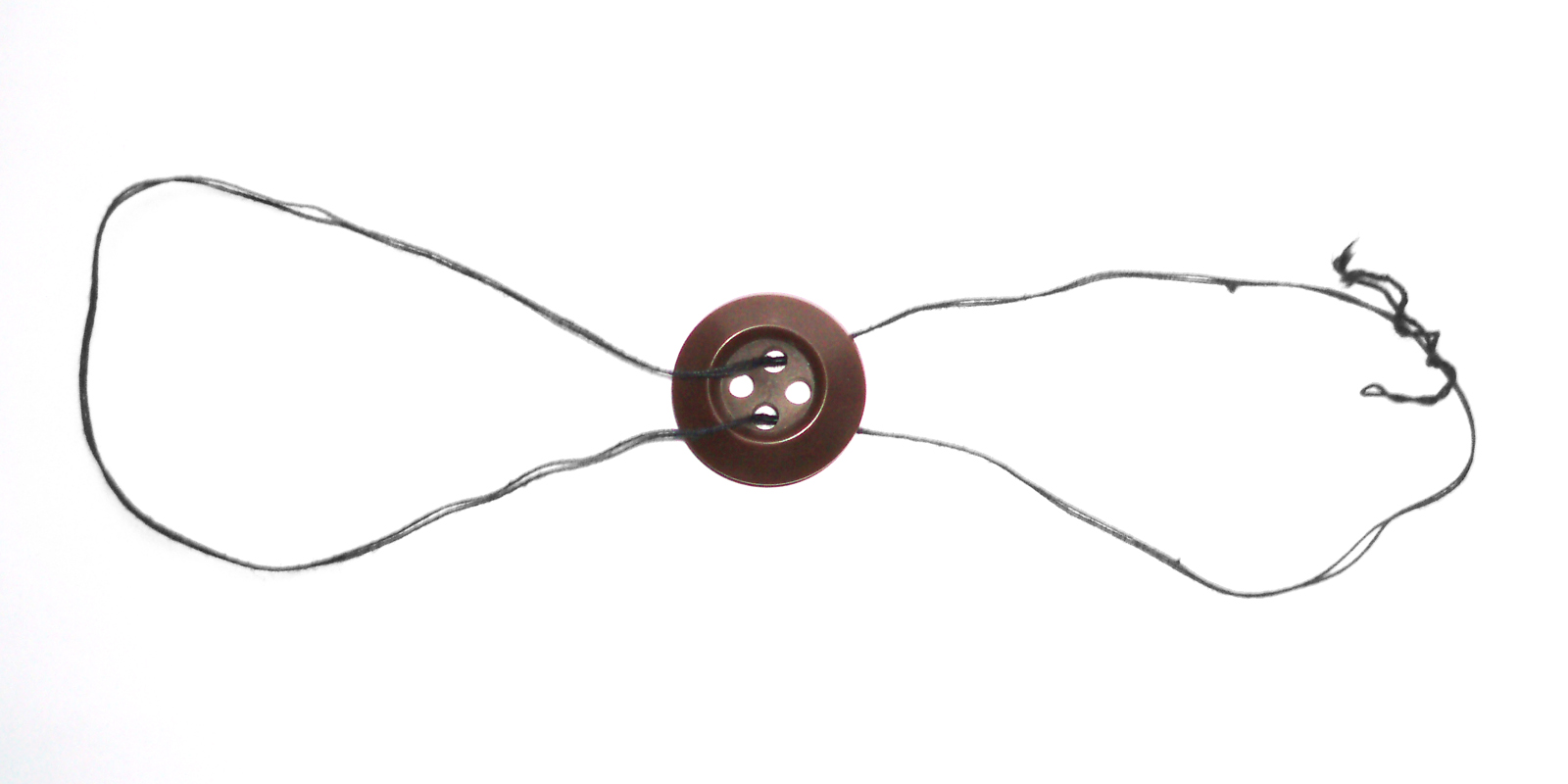

The Stanford team set out to find if there was a way to make a centrifuge on the cheap, and they found inspiration in an unlikely place: an ancient toy called a whirligig.

Whirligigs are simple toys that use pieces of string to make a centrepiece spin, sometimes making a buzzing noise in the process. Their use dates back to about 3,300 BC.

Here's what they look like:

Whirligigs work by winding the string on each side, and having it tethered to a centre point. This can then be pulled to cause the string to unwind and then rewind, spinning the centrepiece very quickly.

As George Dvorsky reports for Gizmodo:

"To make it work, a circular disc is spun by pulling on strings that pass through the centre. The paperfuge works according to the same principle, which the researchers describe as a 'nonlinear oscillator'.

Applying force to the handles unwinds the strings, resulting in rotation of the central disc. Once the strings are completely unwound, they start to rewind, forming a super-coiled structure."

It turns out that this very simple toy also makes the basis for a paperfuge, which the team constructed out of paper, fishing string, wood or PVC pipe for handles, and drinking straws to hold the samples.

Using these materials, the team was able to achieve incredible force on the samples, showing that using nothing but human power and a few items typically found around villages can make sophisticated diagnostic material.

"The paperfuge achieves speeds of 125,000 revolutions per minute [RPM] (and equivalent centrifugal forces of 30,000g), with theoretical limits predicting 1,000,000 RPM," the team writes.

"We demonstrate that the paperfuge can separate pure plasma from whole blood in less than 1.5 [minutes], and isolate malaria parasites in 15 [minutes]."

With their success, the researchers hope to mass-produce handheld paperfuges in the future, saying that the whole device can be made using a 3D printer, averaging to a cost of around 20 cents each.

"The simplicity of manufacturing our proposed device will enable immediate mass distribution of a solution urgently needed in the field," the team writes.

"Ultimately, our present work serves as an example of frugal science: leveraging the complex physics of a simple toy for global health applications."

Check out the video below to see the device in action:

The team's work was published in Biomedical Engineering.