The world's oceans are awash with millions of tiny plastic Lego pieces, and these toys-turned-pollutants are not going anywhere anytime soon.

New research has found those classic Lego bricks take between 100 and 1,300 years to fully disintegrate at sea, depending on variations in the plastic's composition and the marine weathering it experiences.

In 1997, nearly 5 million bits of Lego on a container ship fell overboard. Estimates also predict that over 2 million blocks have been flushed down the toilet by children, and depending on how effective waste treatment was at the time, an unknown proportion of those flushed in the 70s and 80s may be bobbing around in the waves, too.

Spring tides, onshore winds and a sea of plastic left behind.

— Lego Lost At Sea (@LegoLostAtSea) March 10, 2020

A Cornish beach this morning. #Cornwall #oceanplastic pic.twitter.com/BcGYRBIejL

In the past decade, voluntary organisations like the LEGO Lost at Sea Project have recovered thousands of plastic pieces from our beaches, but if these toys are really as sturdy as the new research suggests, we've got our work cut out for us. In all likelihood, these tiny little blocks will keep coming in waves for centuries to come.

"Lego is one of the most popular children's toys in history and part of its appeal has always been its durability," says Andrew Turner from the University of Plymouth, who studies the chemical properties of marine litter.

"It is specifically designed to be played with and handled, so it may not be especially surprising that despite potentially being in the sea for decades it isn't significantly worn down. However, the full extent of its durability was even a surprise to us."

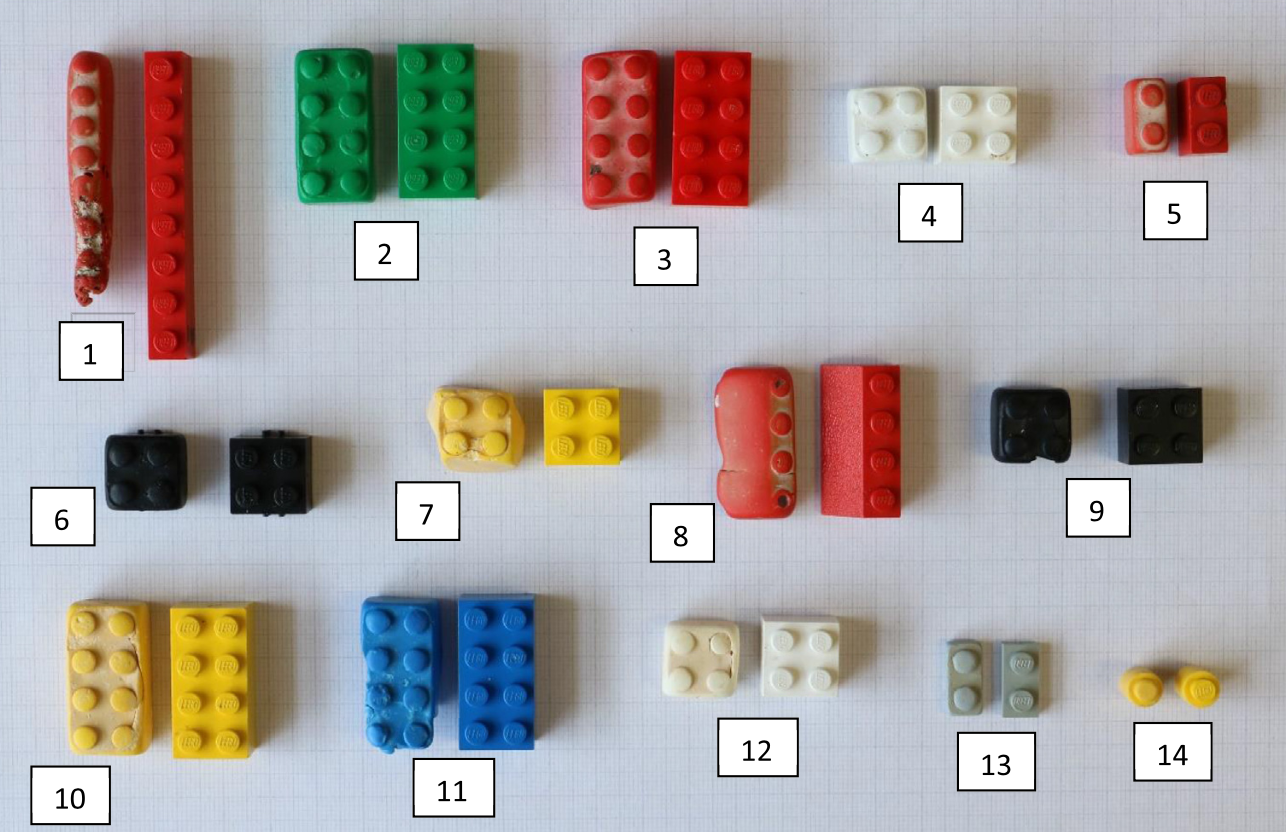

Collecting 50 Lego blocks from the beaches of southwest England, researchers compared chemicals in the weathered samples to archived Lego blocks in their original condition.

(Turner et al., Environmental Pollution, 2020)

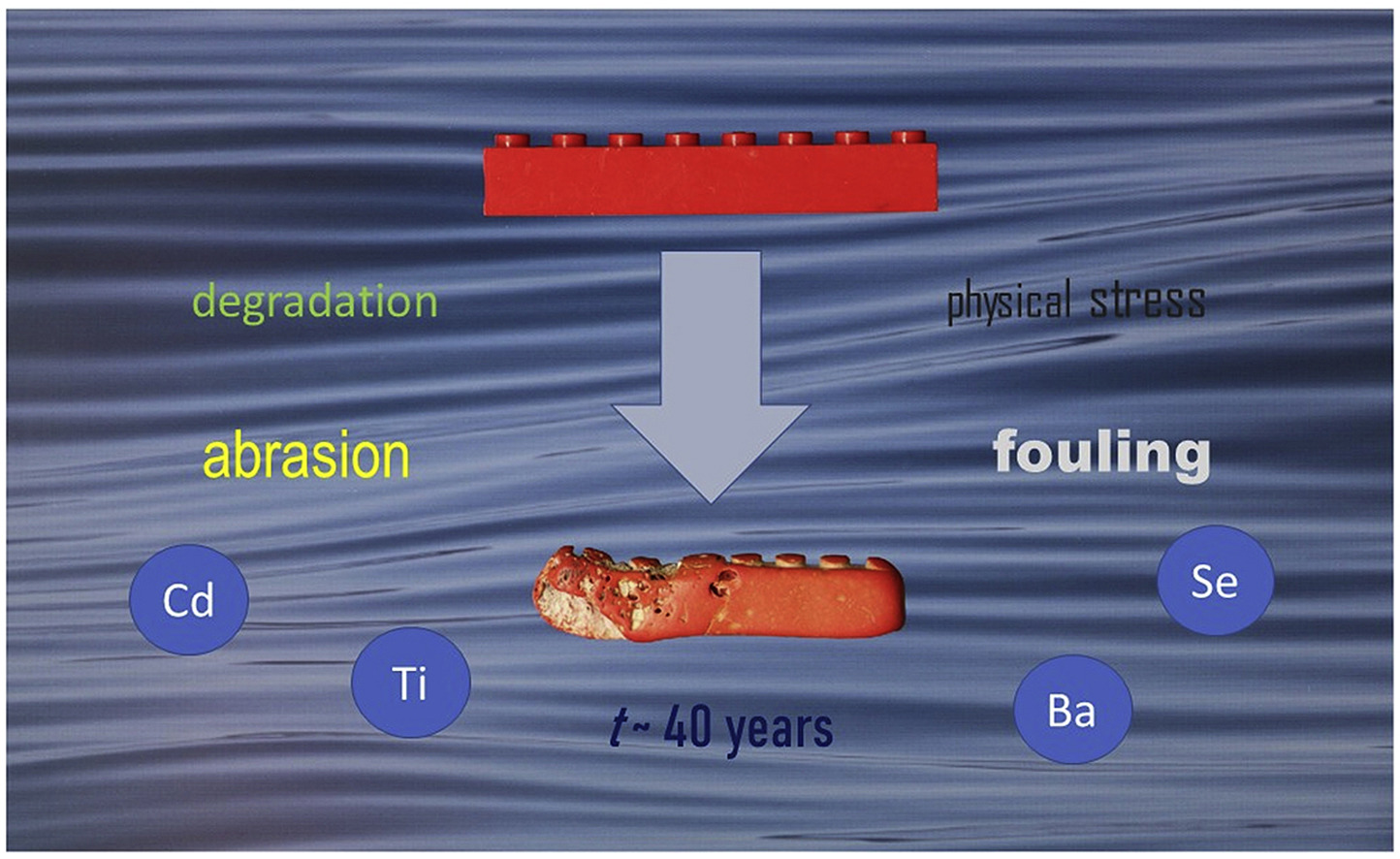

(Turner et al., Environmental Pollution, 2020)

The classic Lego brick is made of acrylonitrile butadiene styrene (ABS), and while the company hopes to use more sustainable materials by 2030, this tough polymer has already done more than enough harm.

While weathered blocks from the beach showed various degrees of weakening, yellowing, blunting, fracturing and fouling, researchers were surprised to find the toys largely intact.

"Based on mass difference among paired samples that are about 40 years old we estimate residence times in the marine environment on the order of hundreds of years," the authors write.

Precisely how these blocks entered the environment is unclear, but they match up with items sold in the 1970s and 80s. And despite decades at sea, they're still doing alright, relatively speaking.

Marine life may have smoothed down their edges, dulled their plasticky shine, stunted their studs and faded their colours, but they are still more than recognisable.

(Turner et al., Environmental Pollution, 2020)

(Turner et al., Environmental Pollution, 2020)

Plastic materials like ABS are too new for us to know what will happen to them in the long run, but studies like this give us some idea of how they've coped so far.

The authors say their findings compare to the life expectancy of clear plastic bottles, and judging by the weathering seen so far, they probably put sea life at similar risk.

"The pieces we tested had smoothed and discoloured, with some of the structures having fractured and fragmented, suggesting that as well as pieces remaining intact they might also break down into microplastics," says Turner.

"It once again emphasises the importance of people disposing of used items properly to ensure they do not pose potential problems for the environment."

The study was published in Environmental Pollution.