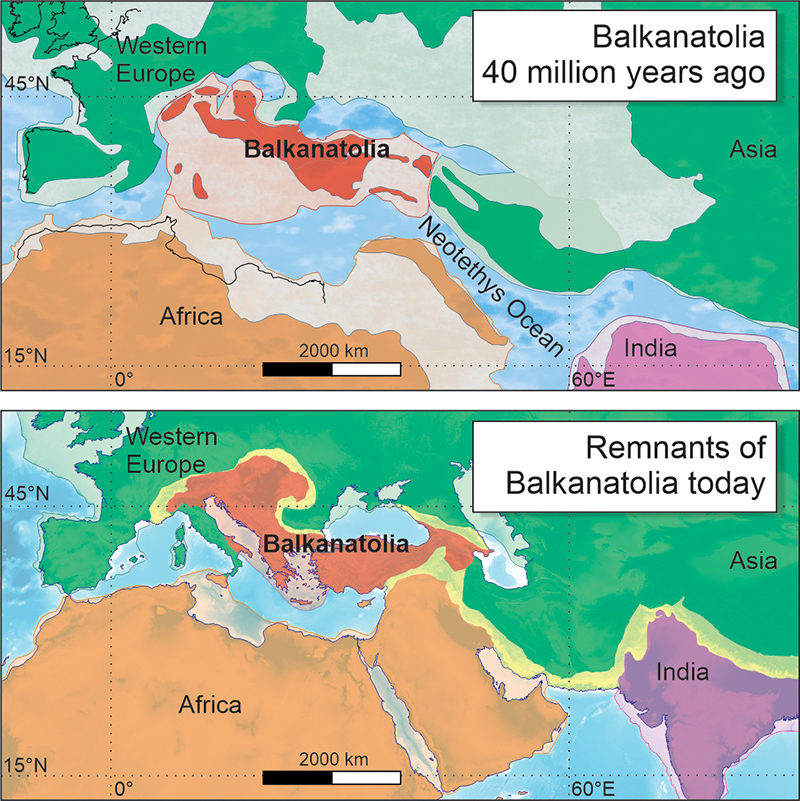

A low-lying continent that existed some 40 million years ago and was home to exotic fauna may have "paved the way" for Asian mammals to colonize southern Europe, new research suggests.

Wedged between Europe, Africa and Asia, this forgotten continent – which researchers have dubbed "Balkanatolia" – became a gateway between Asia and Europe when sea levels dropped and a land bridge formed, around 34 million years ago.

"When and how the first wave of Asian mammals made it to south-eastern Europe remains poorly understood," palaeogeologist Alexis Licht and colleagues write in their new study.

But the result was nothing short of dramatic. Around 34 million years ago, at the end of the Eocene epoch, huge numbers of native mammals disappeared from Western Europe as new Asian mammals emerged, in a sudden extinction event now known as the Grande Coupure.

Recent fossil findings in the Balkans, however, have upended that timeline, pointing towards a 'peculiar' bioregion that appears to have enabled Asian mammals to colonize southeastern Europe as much as 5 to 10 million years before the Grande Coupure occurred.

To investigate, Licht, of the French National Centre for Scientific Research, and colleagues re-examined the evidence from all known fossil sites in the area, which covers the present-day Balkan peninsula and Anatolia, the westernmost protrusion of Asia.

The age of these sites was revised based on current geological data, and the team reconstructed paleogeographic changes that transpired in the region, which has a "complex history of episodic drowning and re-emergence".

What they found suggests Balkanatolia served as a stepping stone for animals to move from Asia into western Europe, with the transformation of the ancient landmass from standalone continent to land bridge – and subsequent invasion with Asian mammals – coinciding with some "dramatic paleogeographic changes".

Balkanatolia, 40 million years ago, and at the present day. (Alexis Licht, Grégoire Métais/CNRS)

Balkanatolia, 40 million years ago, and at the present day. (Alexis Licht, Grégoire Métais/CNRS)

Around 50 million years ago, Balkanatolia was an isolated archipelago, separate from the neighboring continents, where a unique collection of animals distinct from those of Europe and eastern Asia thrived, the analysis found.

Then a combination of falling sea levels, growing Antarctic ice sheets and tectonic shifts connected the Balkanatolia continent to Western Europe, between 40 to 34 million years ago.

This allowed Asian mammals including rodents and four-legged hoofed mammals (aka ungulates) to adventure westward and invade Balkanatolia, the fossil record shows.

Adding to that record, Licht and colleagues also discovered fragments of a jawbone belonging to a rhinoceros-like animal at a new fossil site in Turkey, which they dated to around 38 to 35 million years ago.

Upper molar of an Asian Brontothere mammal. (Alexis Licht, Grégoire Métais/CNRS)

Upper molar of an Asian Brontothere mammal. (Alexis Licht, Grégoire Métais/CNRS)

The fossil is, arguably, the oldest Asian-like ungulate discovered in Anatolia to date and predates the Grande Coupure by at least 1.5 million years, suggesting that Asian mammals were well on their way to Europe via Balkanatolia.

This southern pathway to Europe across Balkanatolia was perhaps more favorable for adventurous animals than traversing higher-latitude routes through Central Asia which at the time were drier, cooler, desert steppes, Licht and colleagues also suggest.

However, they point out in their paper that the "past connectivity between individual Balkanatolian islands and the existence of this southern dispersal route remain debated", and that the story pieced together thus far "is only built on mammalian fossils and a more complete picture of past Balkanatolian biodiversity remains to be drawn".

Many of the geological changes that gave rise to Balkanatolia have yet to be fully understood, and it's important to note that this review is just one team's interpretation of the fossil record.

That said, the fossil record of mammals and other vertebrates living on islands is usually sparse and patchy, whereas the rich terrestrial fossil record of Balkanatolia "provides a unique opportunity to document the evolution and demise of island biotas in deep time," the team concludes.

The study was published in Earth-Science Reviews.