Amid the swarms of small surreal things scuttling and swimming across planet Earth 500 million years ago, a giant loomed.

Titanokorys gainesi, newly discovered in the Burgess Shale fossil formation, would have been a Cambrian colossus, measuring a gobsmacking estimated half a meter (1.64 feet) in length. That may seem small to us now, but at a time when almost everything else was less than a fifth of that size, it's extraordinary.

"The sheer size of this animal is absolutely mind-boggling," said paleontologist Jean-Bernard Caron of the Royal Ontario Museum. "This is one of the biggest animals from the Cambrian period ever found."

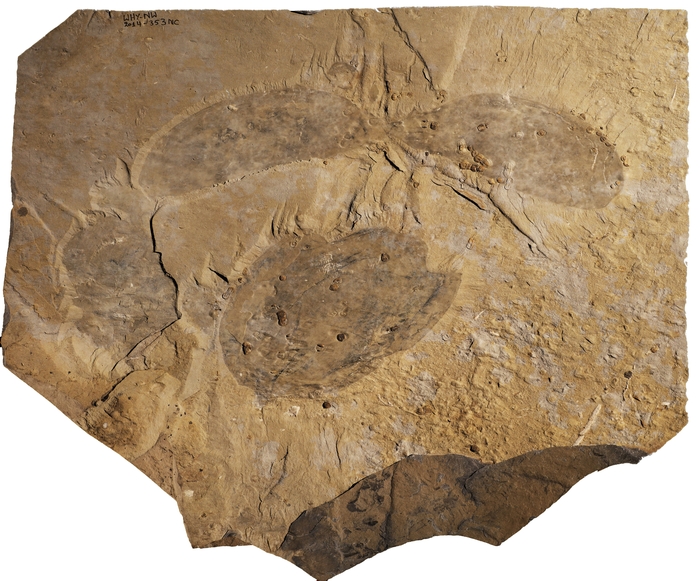

Fossilized Titanokorys carapace. (Jean-Bernard Caron/Royal Ontario Museum)

Fossilized Titanokorys carapace. (Jean-Bernard Caron/Royal Ontario Museum)

The Cambrian period was a momentous time in Earth's history. Around 541 million years ago, over a period of about 25 million years, almost all major forms of animal life suddenly appeared on the scene in an event known as the Cambrian explosion. Nothing else like it has been seen before or since.

But many of the creatures that emerged were really rather strange, at least compared to the life that thrives today. Bristling worms, worms with legs, strange jellies, this weird thing - if you were to travel back in time, you'd be forgiven for thinking you'd been transported to some alien world.

We know about these animals because their imprints are preserved as fossils in ancient shale beds, and perhaps the most well-known of these is the Burgess Shale in Canada. This is where Caron and his colleague, paleontologist Joe Moysiuk of the Royal Ontario Museum, also found multiple traces of their new beast.

(Jean-Bernard Caron/Royal Ontario Museum)

(Jean-Bernard Caron/Royal Ontario Museum)

Above: Titanokorys fossilized carapace (bottom) and plates that protected the underside of the head (top).

Due to the exceptional preservation properties of shale, a sedimentary clay consisting of very fine particles, they were able to identify and then describe the animal in detail. It belongs to an extinct group of Cambrian primitive arthropods known as radiodonts, which included some of the earliest large predators identified.

The largest of these is the infamous Anomalocaris, thought to be the earliest known top predator, with an estimated length of up to a meter (3.3 feet) - but Titanokorys isn't far behind.

"Titanokorys is part of a subgroup of radiodonts, called hurdiids, characterized by an incredibly long head covered by a three-part carapace that took on myriad shapes," Moysiuk said.

"The head is so long relative to the body that these animals are really little more than swimming heads."

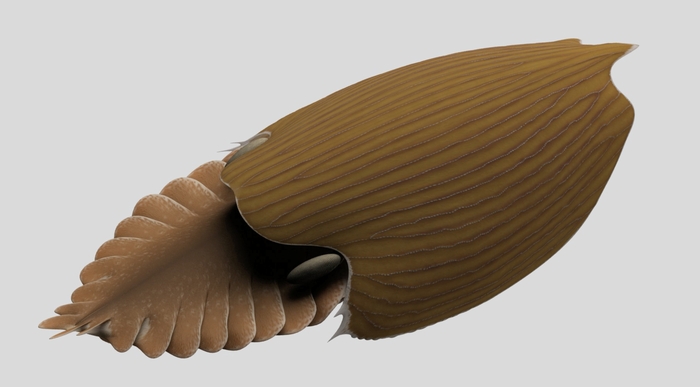

Artist's reconstruction of Titanokorys. (Lars Fields/Royal Ontario Museum)

Artist's reconstruction of Titanokorys. (Lars Fields/Royal Ontario Museum)

Titanokorys shared morphological features in common with all radiodonts. It had multifaceted, stalked compound eyes; a disc-shaped mouth consisting of radiating toothed plates; two long, clawed appendages at the front of its body; and a trunk consisting of multiple flaps that aided swimming, as well as gills.

It's unclear why the larger predatory and smaller sediment- and filter-feeding radiodonts may have both had these physical features. The variation in their sizes could suggest that perhaps radiodonts consumed larger prey, which could explain why both large and small versions of the same animals could thrive.

Titanokorys does differ in one key respect: its outer carapace is broader and flatter than the average radiodont. This suggests that the animal was nektobenthic – adapted to life at the bottom of the sea, near the floor.

And there, the researchers said, it would have dominated.

"These enigmatic animals certainly had a big impact on Cambrian seafloor ecosystems," Caron said.

"Their limbs at the front looked like multiple stacked rakes and would have been very efficient at bringing anything they captured in their tiny spines towards the mouth. The huge dorsal carapace might have functioned like a plow."

The find also underscores how important it is to keep looking, even at something as well known and explored as the Burgess Shale. You never know when a giant Cambrian arthropod might be lurking right under your nose.

The research has been published in Royal Society Open Science.