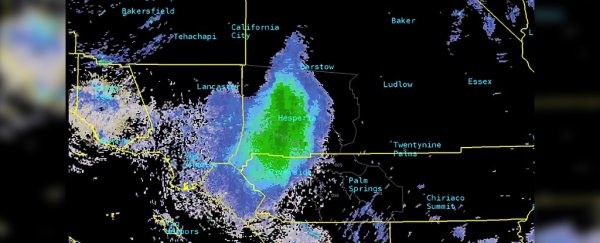

Meteorologists in Southern California got a strange surprise on Tuesday night when they spotted a huge blob on the National Weather Service radar. Appearing to be about 130 by 130 kilometres (80 miles), it was moving southward over San Bernardino County.

"It was very strange because it was a relatively clear day and we weren't really expecting any rain or thunderstorms," meteorologist Casey Oswant of the National Weather Service in San Diego told NPR.

"But on our radar, we were seeing something that indicated there was something out there."

When the meteorologists asked a local weather spotter to eyeball the mass, the LA Times reported, there was no rain, even though the radar signal indicated lots of raindrop-sized objects. The spotters noticed some ladybugs, and concluded the giant weird blob was a tremendous swarm of the spotted red beetles on the move.

The large echo showing up on SoCal radar this evening is not precipitation, but actually a cloud of lady bugs termed a "bloom" #CAwx pic.twitter.com/1C0rt0in6z

— NWS San Diego (@NWSSanDiego) June 5, 2019

It's not clear what kind of ladybugs they could have been, since California is home to around 200 species, but a highly probable contender is Hippodamia convergens, the convergent ladybug, whose primary prey of aphids makes it incredibly popular for garden pest control.

Flying at an altitude of 1.5 to 2.7 kilometres (1 to 1.7 miles), the main mass of the supposed swarm was not nearly as big as it appeared on the radar. Most of it was concentrated in an area just 16 kilometres (10 miles) across, and even then it wasn't a clump, but relatively spread out.

That's still a lot of bugs, though. And although ladybugs do migrate, it's unusual to see that many at this time of year. Typically, they seek out warm locations to try to survive through the snowy winter, returning in spring to feast on a glut of aphids.

Adult aggregation of convergent ladybugs. (Drobincorvette/CC BY-SA 3.0/Wikimedia)

Adult aggregation of convergent ladybugs. (Drobincorvette/CC BY-SA 3.0/Wikimedia)

So, this appearance was "a little bit later than I would have expected them," UC Riverside entomologist Ring Cardé told Reuters.

He suggested that an unusually wet and rainy winter could have seen a larger than usual number of ladybugs survive hibernation. Then, woken by rising temperatures, they started moving en masse to feed.

But Cornell University entomologist John Losey believes there may be more worrying factors at play.

"It's not exactly clear why we're seeing this big swarm now that we haven't before," he told NPR.

"Is that just sort of a random effect of what happened in the weather and the prey populations? Is it having something to do with climate change that's sort of condensing when they all are going to fly?"

The best-case scenario, he said, would be that conditions for ladybug survival are just particularly good in California right now.

Or, it may not even be a swarm of ladybugs at all. Although the team has been working hard to confirm it, they have not turned up any evidence in support of the ladybug idea, and entomologist Steve Heydon of the Bohart Museum of Entomology told The Guardian that temperatures were cooler than ladybugs generally prefer.

And ecologist James Cornett told the Desert Sun that he found the ladybug theory a bit difficult to believe, since the insects usually move in swarms of a few thousand, not the tens of millions that would have been necessary to produce a radar echo.

Meanwhile, the blob itself has literally disappeared off the radar. So it's possible that we'll never know what caused the mystery signal.