Even with all the photos that have been taken of space, there are still new things to be seen.

And you don't always need to be a scientist to find them.

The first blooming light of a star that went supernova has been photographed for the first time - by an amateur astronomer testing a new camera.

Victor Buso from Rosario, Argentina has become the first person to ever capture the optical (or visible) light before and after the "shock breakout" of an exploding star.

This is the point right when the star explodes - when the supersonic shockwave from the star's core breaks out of the surface of the star, causing the gas there to heat and brighten very quickly.

In other words, that's the very, very first burst of light from a supernova.

They're super-difficult to capture, because the exact timing of a supernova is impossible to predict, and the shock breakout lasts such a short duration of time.

Astronomers have been chasing the phenomenon for years.

"It's like winning the cosmic lottery," said Alex Filippenko of UC Berkeley, who led a team following up observations of the supernova in the months that followed.

Indeed, obtaining the photographs involved a concatenation of lucky circumstances for Buso.

He was testing his camera on 20 September 2016, mounted on a 40-centimetre (16-inch) telescope.

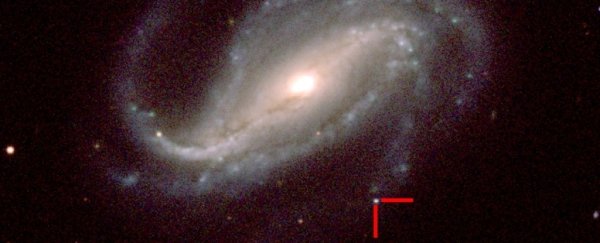

To do this, he picked spiral galaxy NGC 613, located at a distance of about 80 million light-years away in the southern constellation Sculptor - a nice target because it was directly overhead.

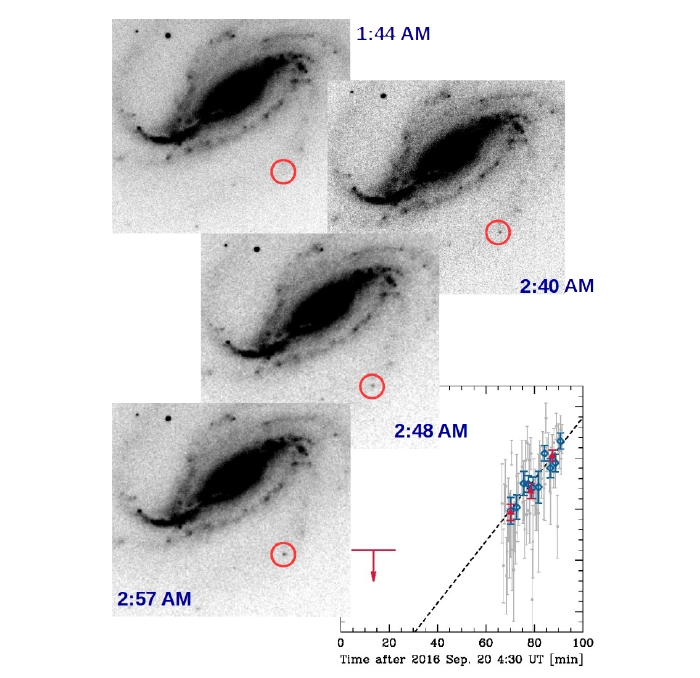

Over the course of about one and a half hours, he took pictures of the galaxy at 20 seconds of exposure time, to avoid saturation by nearby city lights. During the first 20 minutes, the photos all appeared the same.

But then Buso noticed something - a single brightening point of light at the end of one of the spiral galaxy's arms.

It wasn't long before astronomers learned of the find, and realised that Buso had captured something extraordinary.

Negatives of Buso's photographs showing the supernova brightening over time. (Víctor Buso images; Melina Bersten data)

Negatives of Buso's photographs showing the supernova brightening over time. (Víctor Buso images; Melina Bersten data)

According to the researchers, the chances of such a discovery are one in 10 million - maybe even one in 100 million.

"Buso's data are exceptional," Filippenko said. "This is an outstanding example of a partnership between amateur and professional astronomers."

The research team used the Lick and Keck observatories to monitor the supernova, since named SN 2016gkg, for two months following Buso's discovery.

Spectral data revealed it to be a Type IIb supernova - a massive star that has already lost most of its mass prior to exploding.

The team calculated that SN 2016gkg started at around 20 times the mass of our Sun and lost three quarters of its mass, possibly to a companion star.

By the time it went supernova, it had shrunk down to around 5 solar masses.

The long-sought visual data will help astronomers find out more information about a star's structure just before it explodes, as well as information about the explosion itself.

"Professional astronomers have long been searching for such an event," Filippenko said.

"Observations of stars in the first moments they begin exploding provide information that cannot be directly obtained in any other way."

The research has been published in Nature, with Buso as one of the co-authors.