In 1996, over 20 years ago, then US President Bill Clinton made a short speech on what was, at the time, a monumental discovery: one that would someday launch a whole new field of science, called astrobiology.

Embedded in a Martian meteorite, NASA scientists had that day said there could be evidence of a possible sign of life: a Martian rock with structures oddly similar to a primitive bacterial life form.

It was the first time that extraterrestrial life had ever been taken seriously by a sitting president, and although it caused much discussion around the world, many in the scientific community remained skeptical.

It's a scientific controversy that persists to this day. And after years of inconclusive research, the most-argued-about meteorite in history may well have some new competition.

Researchers from Hungary are now claiming to have found a second Martian meteorite that also contains possible organic fossils. Discovered in the late 1970s from the same region of Antarctica, it too could start a long and drawn-out battle over the possibility of life on other planets.

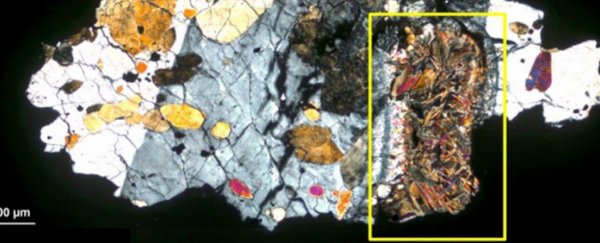

Officially named ALH-77005, this particular Martian meteorite shows features that are oddly reminiscent of iron-oxidising bacteria, including spherical and thread-like structures, a possible signature of mineralised microbes and their alteration of rock.

According to the authors in their peer-reviewed paper, these features "fit well on five hierarchical levels (isotope, element, molecule, mineral, and texture) with complex terrestrial biogenicity features, and also results on other meteorites".

Using optical microscopy and carbon isotope data, the team has thus come to an extraordinary conclusion. They are now proposing that Martian bacteria may have once lived in this meteorite, a sign that life, even at its smallest, could have formerly existed on the Red Planet.

Knowing what we know today, scientists are largely in agreement that there is currently no firm evidence of life on Mars. Nevertheless, NASA continues to assess whether this planet could have once been capable of supporting microbial life long ago.

These meteorites are some of the only clues we have, but while there is little doubt that they do, in fact, come from Mars, there is a lot more contention when it comes to actually interpreting their structures.

As much as these remnants may look like bacteria, the truth is, they may not actually originate from life at all, and to actually prove that they did is extremely tricky, if not impossible.

Essentially, if no physical mechanism can be used to explain something, scientists sometimes propose other kinds of radical hypotheses – but this reasoning has a tonne of flaws, and it's something that we still get wrong here on Earth.

As such, many scientists have warned that the mere presence of bacteria-shaped structures isn't enough to give evidence of anything.

After the first Martian meteorite was suspected of life, James William Schopf, an eminent palaeontologist and expert on early life forms said that while the research was robust, he would also need to see "evidence of cell walls (which keep live bacteria apart from their surroundings), evidence of reproduction (bacteria shapes dividing or budding), evidence of growth (bacteria shapes in a range of sizes, with the largest beginning to divide), and evidence of colonies of cells".

That's a tonne of corroboration that we may never possess.

In short, neither of these findings is conclusive proof of life on Mars.

Instead, it's more accurate to say that this superficial evidence is more consistent with the possibility of ancient life on Mars than with other explanations.

In the words of President Clinton, all those years ago: "Like all discoveries, this one will and should continue to be reviewed, examined, and scrutinised. It must be confirmed by other scientists".

This study has been published in Open Astronomy.