Our world is hugged by complex layers of gases that make up the atmosphere. They protect and nurture all life as we know it. Now, we're shrinking an entire one of those layers – the stratosphere – thanks to the profound impacts we are having on our planet.

An alarming new study has found that the thickness of the stratosphere has already shrunk by 400 meters (1,312 feet) since 1980. While local decreases in the stratosphere's thickness have previously been reported, this is the first examination of this phenomenon on a global scale.

"It is shocking," one of the research team, University of Vigo Earth physicist Juan Añel told Damian Carrington at The Guardian. "This proves we are messing with the atmosphere up to 60 kilometers."

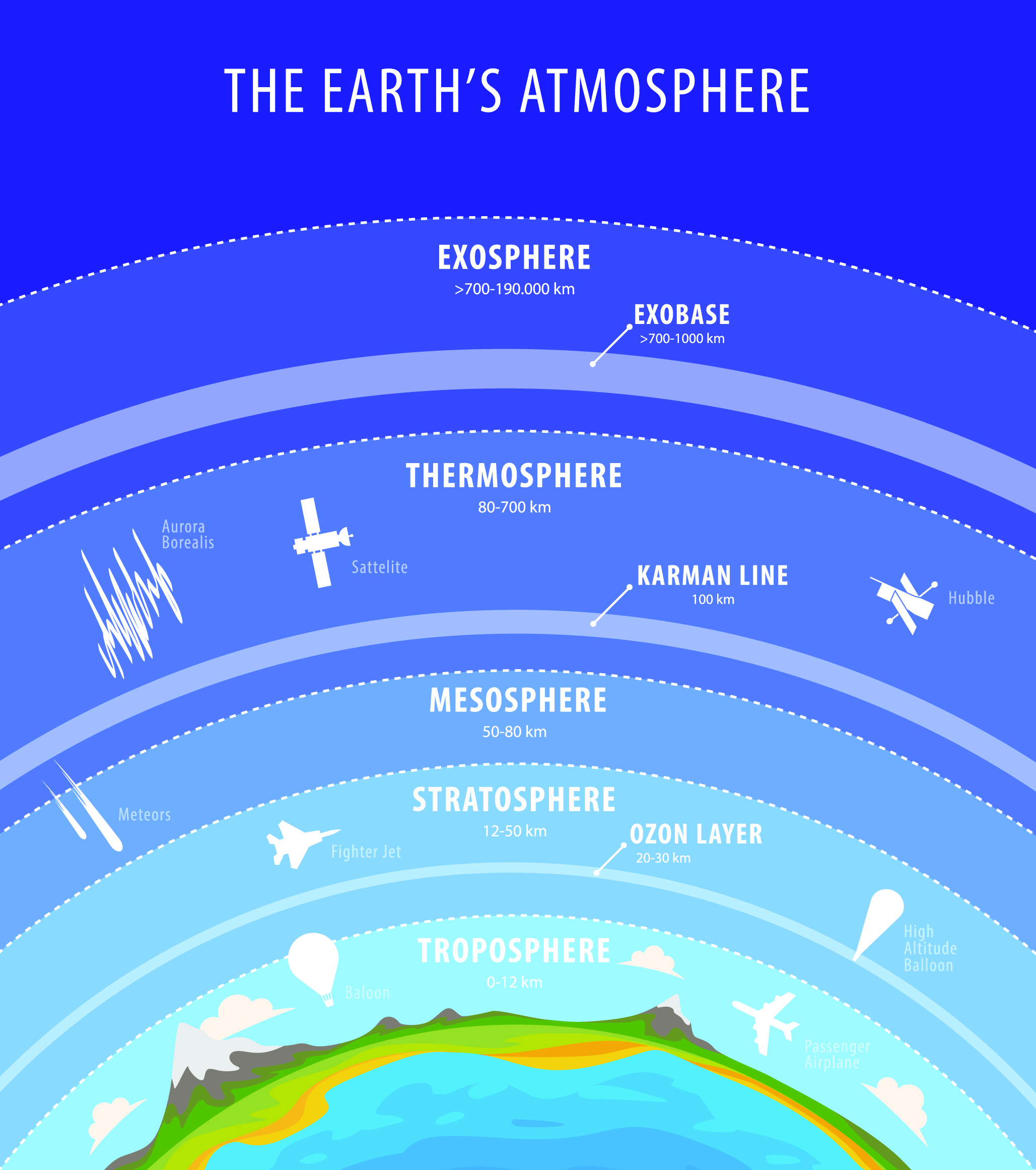

Enveloping the sky around 20 to 60 kilometers (12 to 37 miles) above us, the stratosphere blankets the atmospheric layer we're breathing (the troposphere). Few clouds venture this high and only the occasional birds. It holds the all-important ozone layer, which we've already wreaked havoc upon through our emissions of CFCs.

While collective global efforts have managed to stem ozone depletion, which caused a hole in the ozone layer above Antarctica, our emissions of greenhouse gases have been altering the entire stratosphere.

(shoo_arts/iStock/Getty Images Plus)

(shoo_arts/iStock/Getty Images Plus)

Charl's University atmospheric physicist Petr Pisoft and colleagues used satellite observations since the 1980s combined with climate models to determine that the rise of CO2, rather than previously suspected ozone depletion, is causing the stratosphere to contract.

"[We] demonstrate that the stratospheric contraction is not only a response to cooling, as changes in both tropopause and stratopause pressure contribute," the team wrote in their paper.

Greenhouse gas-induced warming in the troposphere is causing it to expand and squash the stratosphere above it, they explain. On top of this, the addition of CO2 into the stratosphere itself is causing its combination of gasses to cool and huddle closer together (the opposite effect they have on the troposphere) – shrinking the entire layer.

"In a plausible climate change scenario, our planet's stratosphere could lose 4 percent of its vertical extension (1.3 km [0.8 mi]) from 1980 to 2080," Anel told the Anadolu Agency.

(NASA/JSC Gateway to Astronaut Photography of Earth)

(NASA/JSC Gateway to Astronaut Photography of Earth)

Above: Earth's atmospheric layers: troposphere (orange-red) and stratosphere (blue) as viewed from the ISS.

Ozone and molecular oxygen in the stratosphere absorb most of the ultraviolet radiation from the sun, shielding us all from the most harmful sunlight – wavelengths of less than ~300 nm. Here, the air temperature increases with altitude (the opposite of the troposphere beneath), which keeps this layer of gases stable. So aircraft can retreat here when the weather gets rough below, but this stability also means any chemicals that reach the stratosphere tend to linger.

If the predicted changes come to fruition, their scale becomes large enough to potentially affect satellites, GPS, and radio communications, Pisoft and team warned.

It may also change the altitude distributions of absorbing and emitting molecules and therefore alter how the stratosphere absorbs radiation and its overall dynamics, but there is still a lot to figure out before we can understand if and how these impacts would occur.

This is just the latest discovery of the astonishing global-wide impacts the climate crisis has on our world. Another recent find showed the redistribution of weight due to melting glaciers has shifted the Earth's axis.

'It is remarkable that we are still discovering new aspects of climate change after decades of research," University of Reading's atmospheric scientist Paul Williams, who was not involved in the study, told The Guardian.

"It makes me wonder what other changes our emissions are inflicting on the atmosphere that we haven't discovered yet."

This research was published in Environmental Research Letters.