The microbes that inhabit the human gut are thought to be responsible for many things, affecting our health, our genes, and even our emotions.

Scientists are continually making new discoveries about the scale and influence of the human microbiome, but the latest evidence is particularly startling: this thriving bacterial kingdom might not be alone, but could be linked to a separate "human brain microbiome" that resides in your head.

The findings, which are only preliminary at this stage, were recently presented at a poster session at the Neuroscience 2018 annual meeting by researchers from the the University of Alabama in Birmingham.

It's worth mentioning that up front, because these types of scientific presentations are often geared towards sharing results from new or ongoing research that may not have been peer-reviewed by other scientists yet - which is the case here.

The reason that's important is because so far we're still learning how gut microbiota can influence brain function and behaviour, and the new suggestion – that the human brain has its own microbiome population – could be a landmark finding if it can be confirmed in future study.

"This is the hit of the week," neuroscientist Ronald McGregor from the University of California, Los Angeles, who was not involved in the research, told Science.

"It's like a whole new molecular factory [in the brain] with its own needs. … This is mind-blowing."

In the new research, a team led by neuroanatomist Rosalinda Roberts examined brain samples taken from 34 deceased people – about half of whom had schizophrenia, with the other half being considered healthy before they died.

"We did serial section analysis for identification and quantification," the researchers explain in their abstract.

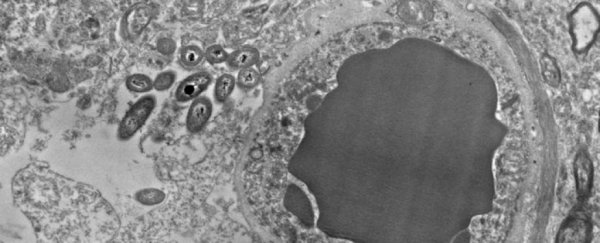

"All cases contained bacteria in varying amounts. Bacteria were rod shaped, and contained a capsule, nucleoid, ribosomes and vacuoles."

The researchers say the density of the bacteria varied according to where it was found in the brain region, with abundant microbes in the substantia nigra, hippocampus, and prefrontal cortex.

They were also found in cells called astrocytes that are increasingly being discovered to play an important role in how neurons communicate.

As for how the bacteria got there, the researchers don't know, but Roberts speculates they could have been transported by blood vessels, finding a home in axons and at the blood brain barrier.

While the team acknowledges it's possible the microbes found their way into the brain tissue by some process of surgical contamination during postmortem operations, the way they were spread throughout the tissue might suggest otherwise.

In any case, subsequent experiments by the team found this bacterial phenomenon isn't restricted to human brains: research with mice also uncovered evidence of the brain microbiome in healthy mice, but not in a separate group of germ-free mice that were raised in isolators to be free from microorganisms.

It's definitely early days, but if future research can help explain the existence of this brain microbiome and how it affects brain cells, it could be a paradigm shift on a par with the discovery of the gut microbiome.

That would be a major step forward in neuroscience, helping cement other related findings in this area of research.

"There is much to investigate," psychiatrist Teodor Postolache from the University of Maryland in Baltimore, who wasn't involved with the study, told Science.

"I'm not very surprised that other things can live in the brain, but of course, it's revolutionary if it's so."

The findings were presented at a poster session at Neuroscience 2018, the annual meeting of the Society for Neuroscience, held in San Diego last week.

H/T: Science