There's a a desert land in the very heart of Eurasia, dry enough to naturally mummify human remains. A Bronze Age discovery has now revealed the secret origins of the people who once called this region of China home.

The Xiaohe people's cattle-focused economy and difference in appearance have long posed questions about their origins. This led to speculation that they may have been the ancestors of migrants.

Researchers have proposed they originated from early dairy farmers of southern Russia (Afanasievo) or central Asian oasis farmers with Iranian plateau links.

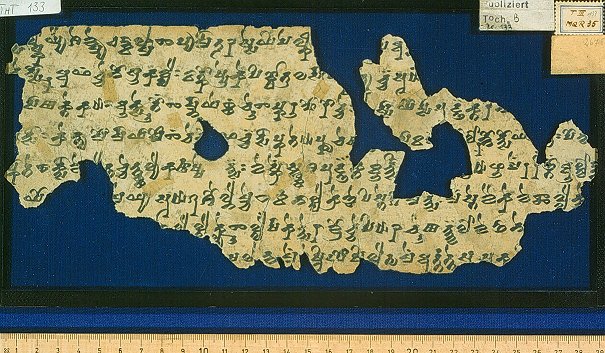

A fragment of Tocharian B from a Buddhist kingdom at Tarim Basin edge. (Public Domain)

A fragment of Tocharian B from a Buddhist kingdom at Tarim Basin edge. (Public Domain)

But a new genomic study that included analysis of the earliest discovered human remains of the region, has found that Xiaohe originated from an ancient Pleistocene population of hunter-gatherer humans that had largely disappeared by the end of the last ice age.

"Archaeogeneticists have long searched for Holocene Ancient North Eurasian populations in order to better understand the genetic history of Inner Eurasia. We have found one in the most unexpected place," said Seoul National University population geneticist Choongwon Jeong.

The Tarim basin, in what's now China's Xinjiang Region, is a dry inland sea with small oases and riverine corridors, fed by runoff from the isolating high mountains that surround it. Human activity here can be dated back to at least 40,000 years ago, and it's long been an intersection between the East and West – as a place along the renowned Silk Road.

Hundreds of human remains, naturally mummified by arid, cold, and salty soils, have been discovered in this basin since the 1990s. These brown-haired and long-nosed people were buried within unique coffins, like upside-down boats, in cemeteries.

Aerial view of the Xiaohe cemetery. (Wenying Li/Xinjiang Institute of Cultural Relics and Archaeology)

Aerial view of the Xiaohe cemetery. (Wenying Li/Xinjiang Institute of Cultural Relics and Archaeology)

They were accompanied by felted and woven woolen clothing, bronze artifacts, cattle, sheep, goats, wheat, barley, millet, and even cheese.

Their farming and irrigation techniques suggested a link to the desert people with ties to the Iranian plateau. Others suspected they came through the Eurasian steppe from Russia, like their northern Dzungarian Basin neighbors.

They have even been associated with the movement east of Indo-European group of languages (from which English eventually emerged), as Buddhist texts from the Tarim Basin hold records of Tocharian, a now extinct branch of this family of languages.

However, after analyzing the genomes of 13 individuals of the Tarim Basin (from 2100 to 1700 BCE) along with five Dzungarian individuals (from 3000 to 2800 BCE), Jilin University geneticist Fan Zhang and team found none of these proposed origins were correct.

The Tarim mummies belong to an isolated gene pool of ancient Asian origins that can be traced all the way back to the early Holocene 9,000 years ago, well before Bronze Age farming communities emerged. This group of once hunter-gathers were likely to have had a much wider distribution previously, as their genetic traces are found through to Siberia.

"Despite being genetically isolated, the Bronze Age peoples of the Tarim Basin were remarkably culturally cosmopolitan, " explained Harvard University anthropologist Christina Warinner. "They built their cuisine around wheat and dairy from West Asia, millet from East Asia, and medicinal plants like Ephedra from Central Asia."

The Xiaohe people look to be the most direct ancestors of pre-farming Asian populations that we know of, the researchers said. Their northern neighbors from the Dzungarian Basin also seem to be a mix of this ancient population as well as the Siberian migrants.

"The Tarim mummies' so-called Western physical features are probably due to their connection to the Pleistocene Ancient North Eurasian gene pool," the researchers wrote in their paper, explaining that the extreme genetic isolation kept them different from neighboring groups. This points "towards a role of extreme environments as a barrier to human migration."

This research was published in Nature.