If fossil fuel emissions do not dramatically decrease and soon, a new study suggests the various ecosystems of life on our planet will be rapidly transformed, especially in the tropics and polar regions.

Instead of predicting the future of a single species or a specific habitat under climate change, the current research categorizes Earth into general 'life zones', which are landscape-scale ecosystem types that share similar temperatures, humidity, and dryness.

In the end, researchers put together a global map that contains the locations of 48 possible life zones on Earth, including tropical forests, temperate forests, deserts, boreal forests, grasslands, and shrublands.

Using historic climate data and climate projections spanning 180 years, they then modelled what has happened to the distribution of these zones in the past and what might happen in the future.

Today, the findings indicate the boundaries between some life zones have already begun to shift, albeit to a minor extent.

While most eco regions currently hold the same life zones as they did a century ago, about 30 have experienced significant changes thus far, either shrinking, expanding, or shifting in range.

(Elsen et al., Global Change Biology, 2021)

(Elsen et al., Global Change Biology, 2021)

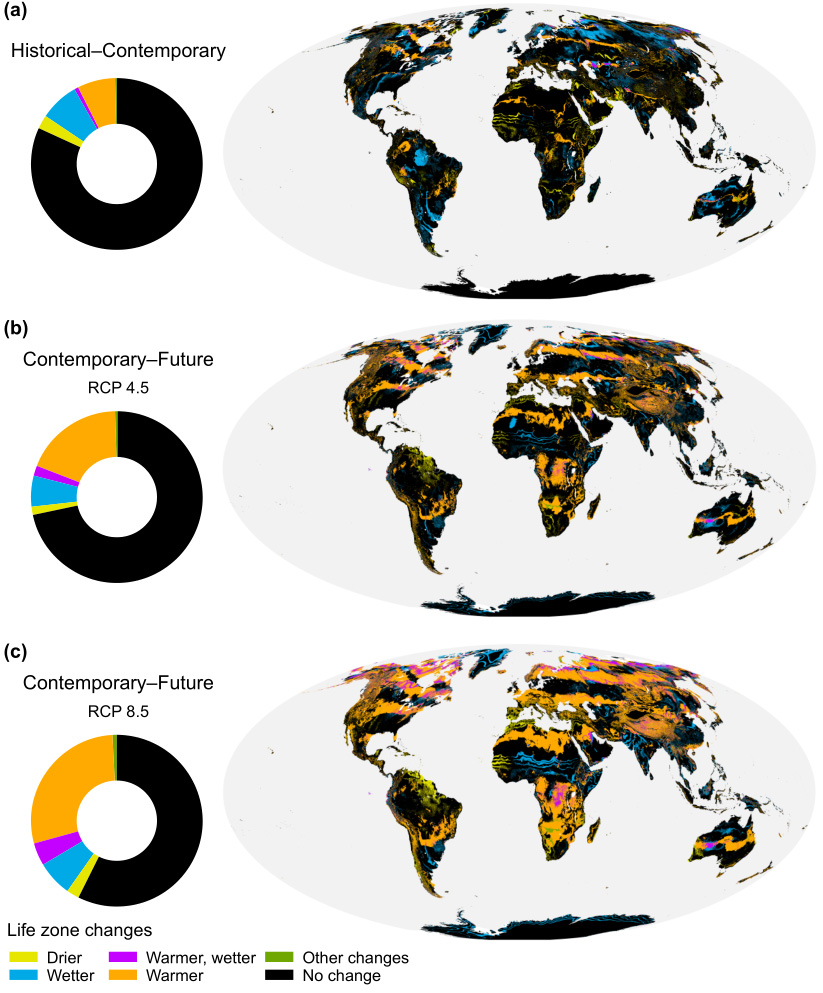

Above: Comparison maps show life zone area changes across three time periods (1901-1920, 1979-2013, and 2061-2080), where future calculations are based on a less severe emissions scenario labelled RCP 4.5, and a scenario where emissions remain at 'business as usual', labelled RCP 8.5.

These changes are most notable among boreal forests, montane grasslands and shrublands, deserts, and temperate coniferous forests. But if we don't do anything to curb our emissions, the yearly changes experienced by Earth's life zones at the moment could triple by 2070.

That means in just five decades, 281 ecoregions could suffer significant life zone changes.

"Importantly, the projected rate of future life zone change is much faster than the past, including in most ecoregions and within all biomes on Earth," the authors conclude.

The model isn't perfect; it only indicates potential ecosystem change. Life zones are broad categorizations that don't include the numerous nuances of an ecosystem, which can also be impacted by climate change, like the physical constraints of plant growth or animal reproduction.

This means the results are likely an underestimation of how much change should be expected under current climate projections.

Still, given how little we currently know about larger zones of life and how they will fare in the future, this research is an important start. It could help guide adaptive conservation and sustainable development strategies to those areas of our planet most vulnerable to climate change.

In species-rich areas like the mountain rainforests of Borneo or Indonesia, for instance, the authors found evidence of a nearly 50 percent turnover in life zone area.

Global conservation efforts should therefore be focused on places like these, where high levels of change threaten vast numbers of species that are unable to adapt in time.

"Policies and practices that are mismatched with life zone changes are likely to misallocate their limited resources and fail to meet biodiversity conservation and sustainable development goals," the authors explain, "especially in regions where the pace of change is greatest and the climatological thresholds for failure are already near."

The tropics and the polar regions of our planet are the areas changing the fastest.

The life zones of tropical rainforests, for example, are likely to expand into other neighboring life zones as climate change worsens. Meanwhile, life zones associated with tundra are likely to shrink in size.

Not only do the new projections highlight where life zones are changing the most, they also identify possible climate sanctuaries. Even under the worst emissions scenario, the current model suggests about 57 percent of all the land area on Earth will still house the same life zones.

These stable ecoregions appear to be located mostly in the Amazon and Congo Basins, the Sahara desert, southeast Asia, and southern Australia. While these areas won't be immune to climate change by any means, the risk of their ecoregions transitioning to a different life zone is low.

"Consequently, places that will experience the least climate change in the near future – and places where life zones will persist unchanged – represent those with the highest potential for Anthropocene refugia," the authors write.

"Provided that local extinction does not occur there due to non-climate factors, stable life zones provide the places where biodiversity is most likely to persist, adapt, and even speciate."

These new maps give us a glimpse into that possible future.

The study was published in Global Change Biology.