There's a lot we can learn by looking at all those voids making space between galaxies - and now, for the first time, astronomers have used a new method to peer inside these mysterious pockets of nothingness.

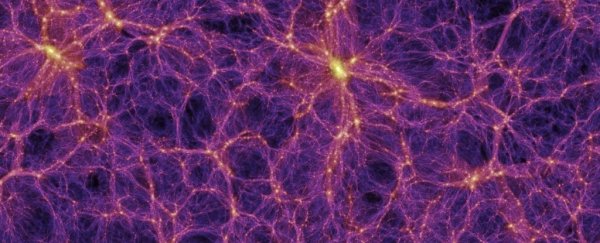

Voids in space are due to the expansion of the Universe - this results in a web of material with spaces in between the filaments. Think of pulling apart a grilled cheese sandwich, if the cheese were made of strings of galaxies.

Cosmic voids can be detected in something called the cosmic microwave background (CMB), a remnant of electromagnetic radiation left behind by the Epoch of Recombination around 380,000 years after the Big Bang.

The CMB represents the first light appearing in the Universe, and in it, cosmic voids seem to correlate with temperature. Hotter regions are associated with the filaments, and the colder regions associated with the voids.

Now, for the first time, researchers have used this CMB map to study the cosmic voids. Led by David Alonso of Oxford University in the UK, a team of researchers has mapped 774 cosmic voids to the CMB to study the properties of the gas that floats therein.

They used data from something called the Baryon Oscillation Spectroscopic Survey (BOSS), which surveyed sound waves that rippled through the early universe like ripples through a pond, and can still be detected throughout the Universe as regular fluctuations in the normal matter.

It also revealed the locations of cosmic voids throughout the Universe, and it was this data that the team stacked against the CMB. They then compared the energy of the CMB photons in each void to its modelled electron pressure to deduce the properties of the gas.

They found that the pressure inside voids is lower than the cosmic average, which isn't an unexpected result. There's not a lot of material in voids, and not a lot happening.

But they found something else, too - clues that the gas might be warmer than they expect it to be.

"If this finding holds up to scrutiny," Christopher Crocket explained in an article for the American Physical Society, "it could be a sign that powerful jets from supermassive black holes are pumping energy into the intergalactic gas and helping to shape the cosmos."

That would be pretty huge news - after all, we've only just discovered that winds from supermassive black holes could be shaping entire galaxies, never mind cosmic voids, which can span billions of light-years.

We may be waiting for some time to find out, though. A more in-depth survey, possibly from a more powerful telescope than the ones currently available, will likely be required to verify if the data is showing what it seems to be showing.

The team's research has been published in Physical Review D.