Earth is getting a special celestial visitor this week in the shape of comet C/2018 Y1 Iwamoto - this sparkling, green-hued hunk of ice and minerals is already visible in the night sky through telescopes and even binoculars.

It's the first binocular comet of 2019 – which means a comet that's visible from Earth through binoculars, as you might have guessed from the name; we only get a few of them each year.

This particular comet was only discovered a couple of months ago – credit due to amateur astronomer Masayuki Iwamoto – and the icy rock is calculated to take 1,371 years to orbit the Sun on a stretched out, elliptical path.

The closest C/2018 Y1 Iwamoto is going to get to us is 45 million kilometres (or 28 million miles): that's 2.5 light-minutes, or around 118 times further out than the Moon. Thanks to its distinctive green glow though, you can spot it using your own equipment.

Why the glow? It's typical of comets like C/2018 Y1 Iwamoto, and it's caused by the heat and radiation from the Sun – those forces create a comet coma, as melted ice from its surface releases gas and dust that are made visible to the human eye when they get struck by ultraviolet light out in space.

Last year this effect was so prominent in one passing comet that it got named The Incredible Hulk. The new rock isn't quite so angry, but should still be visible.

Head over to In-The-Sky.org for a useful finder chart that can help you pinpoint exactly where the Iwamoto comet is going to be on the day you're reading this, so you can maximise your chances of catching a glimpse.

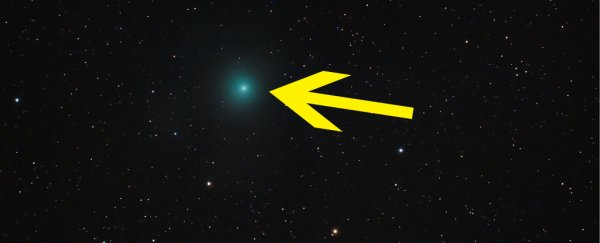

Comet C/2018 Y1 Iwamoto top left, with the Messier 104 spiral galaxy bottom right. (Ian Griffin/Otago Museum)

Comet C/2018 Y1 Iwamoto top left, with the Messier 104 spiral galaxy bottom right. (Ian Griffin/Otago Museum)

Better be quick with your telescope and camera though: the celestial body is zooming around the Solar System at roughly 238,000 kilometres per hour (or 148,000 miles per hour). It's not going to stick around forever.

The comet has just passed the Sun, and here on Earth it will be seen travelling through the constellations of Leo, Cancer and Gemini, before it leaves our sight and shoots towards the outer reaches of the Solar System again.

Technically, it's what's known as an Extreme Trans-Neptunian Object, a collection of objects way, way beyond Pluto – reaching perhaps as many as five times further away from the Sun as the dwarf planet.

We'd really encourage you to get out into the garden and have a spy at C/2018 Y1 Iwamoto as it passes though: it's not scheduled to return to the inner Solar System until the year 3390.