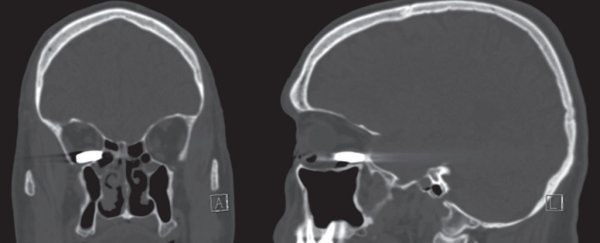

Talk about a close escape: the image that you can see above is a CT scan of the skull of a 45-year-old US man who admitted himself to an emergency room, after being shot with a .22 calibre pistol.

Yes, that bright white slug shape is the bullet – lodged in the man's right eye socket, right up against a muscle that controls eye movement.

While the squeamish among us might struggle to look for very long at the picture, a team of scientists from the University of California, San Francisco have taken the opportunity to study the impact and damage caused by the bullet before it was removed by doctors.

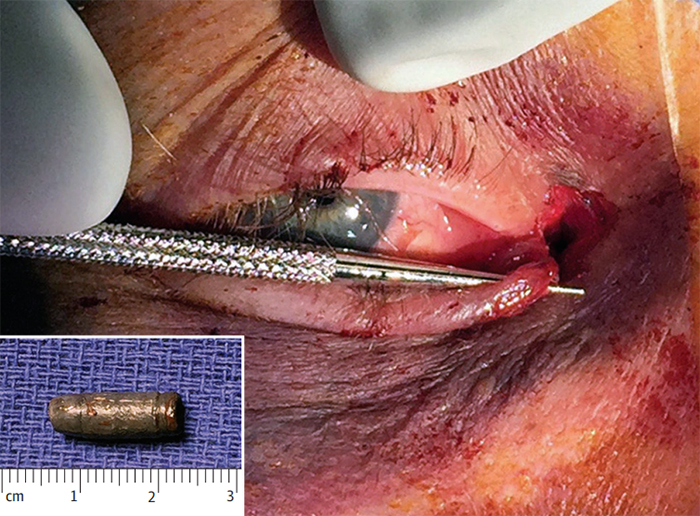

First the good news: the bullet was successfully taken out and hasn't caused any long-term problems with the man's vision, though he of course has a scar to show for his troubles.

An orbitotomy was performed on the eye to remove the bullet. (JAMA Ophthalmology)

An orbitotomy was performed on the eye to remove the bullet. (JAMA Ophthalmology)

Now the more painful details: upon admission the man was in severe pain. The path of the bullet damaged ducts in the eyelid used to drain tears, though it could've been worse – the projectile was slowed down by passing through a door, the researchers note.

That seems to have been crucial in saving the man from a much worse fate. You don't need to be an expert to know a bullet to the head can easily be fatal, or at least the cause of some major destructive damage to bone and tissue.

The unfortunate victim already had a history of amblyopia (or lazy eye) and exotropia, where the eyes deviate outwards.

On top of that, the unwelcome arrival of the bullet caused the eye to slip some 3 millimetres (0.12 inches) out of its socket, a bulging technically known as exophthalmos. Ecchymosis, or a bruising skin discolouration, was also noted by the report as a result of the bullet.

"Projectile injury to the orbit is a function of size, speed, and trajectory," write the researchers in their paper. "Air and BB gun pellets are small with limited velocity and typically come to rest within the orbit, causing minimal soft tissue injury."

"Conversely, bullets are larger and travel at much higher speeds, often resulting in significant destruction to the orbit, adjacent sinuses, and brain."

In other words, the man in question was lucky, or as lucky as you can get if you've just been shot. The wooden door slowed down the velocity of the bullet and it didn't penetrate the actual eye – as long as the eye globe itself isn't hit, vision isn't permanently affected in around 95 percent of cases like this.

The finished report also acts as a guideline for doctors who need to decide whether to operate based on a whole host of factors, including the damage that's been done, how accessible the bullet is, and how much pain the patient is in.

In this case an orbitotomy, or surgical incision into the eye socket (orbit), was carried out. The pain was rapidly reduced and the man's vision wasn't affected.

What the report doesn't say is how the man came to be shot in the first place – let's hope it was some unfortunate accident rather than anything else. At least he now has a rather striking image as a souvenir for all the pain he went through.

The research has been published in JAMA Ophthalmology.