US experts scrambled in the spring to predict what the future of the pandemic might look like. Many predicted that the coronavirus – like the seasonal flu – would retreat in the summer before roaring back in a second, more severe wave come fall.

But epidemiologists are now eschewing that idea.

"There's no evidence there's going to be a decrease in cases, a trough," epidemiologist Michael Osterholm told Business Insider. "It's just going to keep burning hot, kind of like a forest fire looking for human wood to burn."

Osterholm helped write an April report that outlined what a second wave in the fall might look like. At the time, he pegged it as the likeliest of three possible scenarios.

"But now we see there are no waves," he said.

Instead, according to World Health Organisation spokesperson Margaret Harris, the pandemic is probably "going to be one big wave."

'Peaks and valleys in different locations at different times'

Osterholm works as director of the Centre for Infectious Disease Research and Policy (CIDRAP) in Minnesota. The second-wave scenario the group described in April was in part based on the trajectories of the 1918 Spanish influenza and 2009 H1N1 flu pandemics.

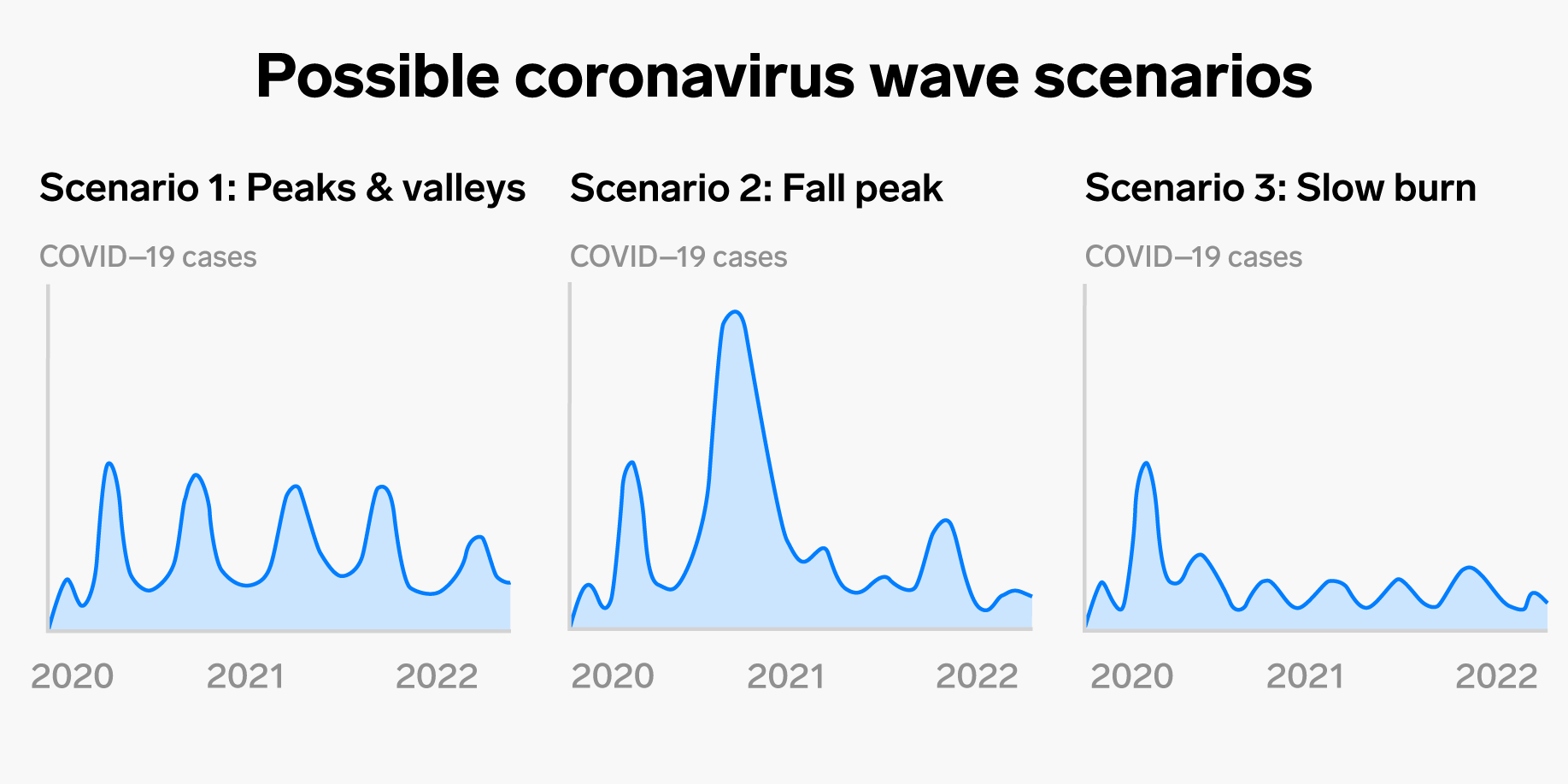

A graphic showing the CIDRAP group's three scenarios for future coronavirus waves. (Ruobing Su/Business Insider)

A graphic showing the CIDRAP group's three scenarios for future coronavirus waves. (Ruobing Su/Business Insider)

Another scenario in the report suggested that the first wave of COVID-19 infections may be followed by a cycle of slightly lower peaks and valleys throughout the summer and beyond. The third scenario involved a "slow burn" of ongoing transmission and new cases following the spring peak in infections.

But reality hasn't aligned with any of those scenarios.

"In April, we were still looking at at whether this was a pandemic where we'd see true waves – where you see big increase in cases and then a trough and then a second, bigger wave for reasons completely beyond human behaviour- which has historically happened with other influenza pandemics," Osterholm said.

Instead, he added, the pandemic is more like "one long-term fire" – so we're in the middle of "a fast burn scenario with peaks and valleys in different locations at different times."

This virus is not seasonal – yet

Respiratory viruses like the flu are seasonal because cooler temperatures help harden a protective gel-like coating that surrounds the virus. A stronger shell ensures it can survive long enough to travel from one person to the next, whereas that sheath dries out faster in warmer temperatures.

Like the flu, the new coronavirus spreads via droplets that people emit when coughing, sneezing, or talking, and both viruses can be transmitted even when infected people show no symptoms.

Those similarities made past flu pandemics a worthy model for early comparisons, especially the 1918 Spanish flu, which infected 500 million people. But the coronavirus isn't seasonal like its viral brethren.

"People are still thinking about seasons. What we all need to get our heads around is this is a new virus," Harris said last week.

"Even though it's a respiratory virus, and even though respiratory viruses in the past did tend to do this, you know, different seasonal waves, this one is behaving differently," she added.

There's a reason the coronavirus is unaffected by the seasons, according to Rachel Baker, a researcher at Princeton's Environmental Institute: "We're at the start of pandemic, when a new virus is emerging into a population that hasn't had it before. So a lack of population immunity becomes a key driver of spread, and climate doesn't really matter very much at first," she previously told Business Insider.

Her recent research, published in May, showed that warm weather only curbs a virus' spread after a large chunk of the population becomes immune or resistant to infection.

It's possible, however, that the coronavirus will "settle into that classic seasonal pattern with a peak in winter months" after about two to three years, Baker said – after a vaccine is developed and distributed.

This article was originally published by Business Insider.

More from Business Insider: