Things are not looking good for Earth's glaciers. Usually, when it comes to climate change and melting ice, we think of the Earth's polar regions.

But they're not the only important ice formations, and they're not the only ice that's melting due to climate change.

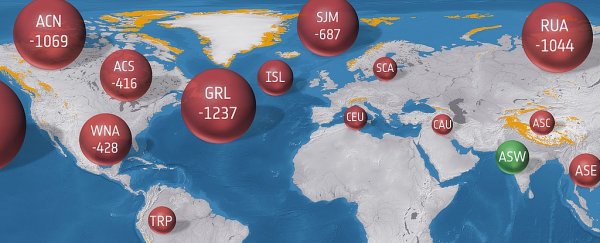

New research published on 8 April 2019 shows that the Earth's glaciers have lost over 9,000 gigatons of ice since 1961. That's over 9 trillion tons. And as a result, they have caused the seas to rise by 27 mm (1.06 inches) since then.

The research comes from an international team led by scientists at the University of Zurich, Switzerland. They relied on glacier measurements, both from the ground and from satellites, taken over the last 50 years.

They focused on 19 glacier regions around the world, including Alaska, Greenland, and the Andes.

(ESA/Zemp et al. (2019) Nature/World Glacier Monitoring Service)

(ESA/Zemp et al. (2019) Nature/World Glacier Monitoring Service)

At the heart of this research is the European Space Agency's (ESA) Climate Change Initiative. That program gathers important climate change data and organizes it, archives it, and makes it available to researchers.

The CCI has a glacier monitoring program, and it provided researchers with the outlines of glaciers and with information on the changes in ice mass for thousands of glaciers around the world.

Frank Paul, from the Department of Geography at the University of Zurich, and co-author of the study had this to say in a press release:

"Glacier outlines are needed to make precise calculations for the areas in question. To date, this information came largely from the US Landsat satellites, the data from which are delivered to European users under ESA's Third Party mission agreement.

In the future, the Copernicus Sentinel-2 mission, in particular, will increasingly contribute to the precise monitoring of glacier change."

This study is based on a cornucopia of data sources. The Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency's ASTER sensor on the US Terra mission and Germany's TanDEM-X mission featured prominently.

Their data was used to construct Digital Elevation Models (DEMs), which give 3D topographic details of a region.

All this data was combined with the comprehensive glaciological database compiled by the World Glacier Monitoring Service. It was used to reconstruct the changes in ice thickness for over 19,000 glaciers around the world. That's how researchers arrived at the 9 trillion ton number.

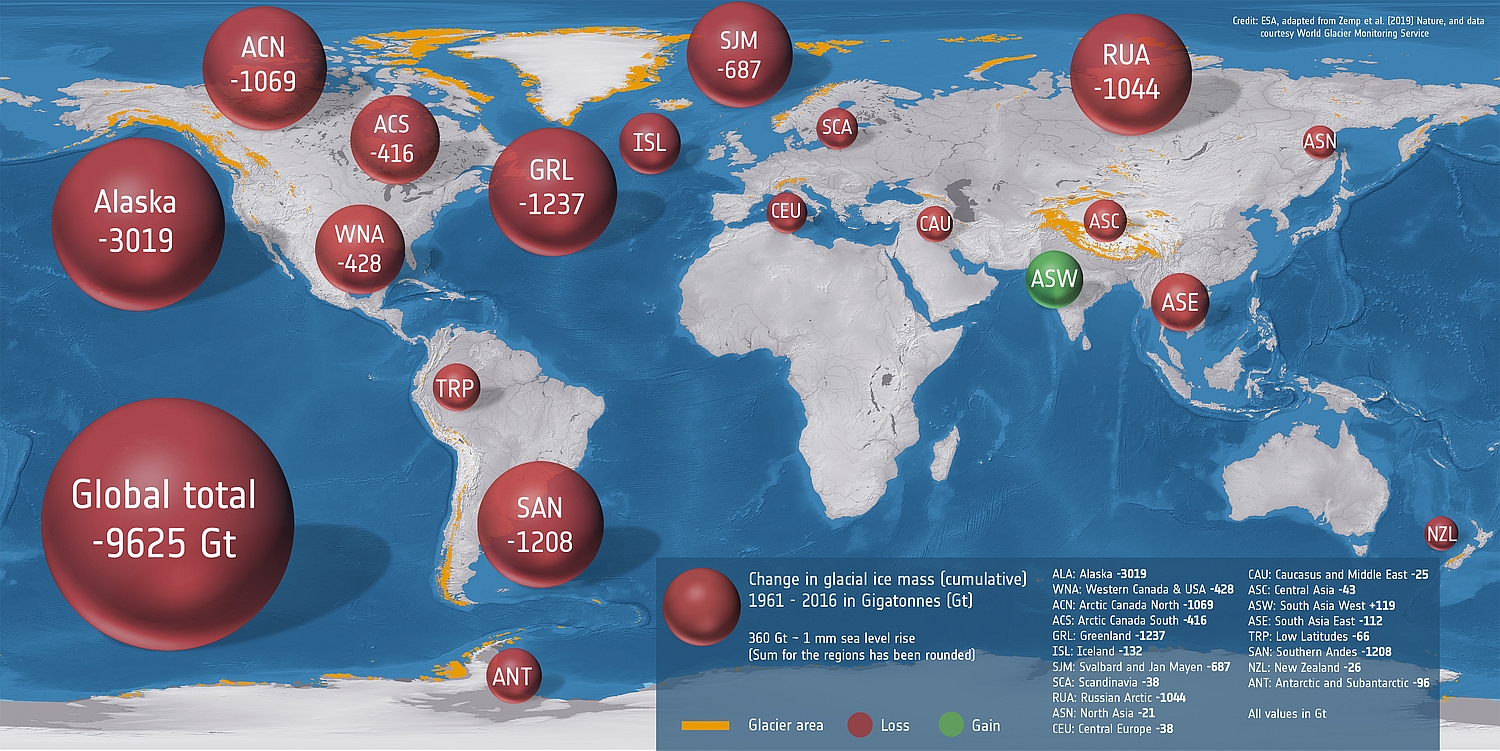

Nordenskiold Glacier Greenland ( Copernicus Sentinel data (2017)/ESA/CC BY-SA 3.0)

Nordenskiold Glacier Greenland ( Copernicus Sentinel data (2017)/ESA/CC BY-SA 3.0)

Michael Zemp, of the Department of Geography at the University of Zurich, was the research leader in this study:

"While we can now offer clear information about how much ice each region with glaciers has lost, it is also important to note that the rate of loss has increased significantly over the last 30 years. We are currently losing a total of 335 billion tonnes of ice a year, corresponding to a rise in sea levels of almost 1 mm per year."

"In other words, every single year we are losing about three times the volume of all ice stored in the European Alps, and this accounts for around 30 percent of the current rate of sea-level rise," added Zemp.

Glaciers, along with ice caps, are the world's largest source of fresh water. But it's glaciers that release their water into human communities. Shrinking glaciers means less water for people, less water for irrigation, and less water for hydroelectric power generation. And then, of course, there's wildlife.

All of that means some critical decisions and planning choices need to made, and they need to be well-planned in advance. That's what this data is meant to help. Only with accurate, long-term data can we plan effectively for climate change.

"It is fundamental that we build upon existing monitoring capabilities using observations from the EC's Copernicus Sentinel missions, and other ESA and Third Party Mission missions. Their data crucially allow us to build a robust climate perspective to reveal regional and year-to-year fluctuations of glaciers and other parts of the cryosphere such as snow cover, sea ice and ice sheets," said Mark Drinkwater, Senior Advisor on cryosphere and climate at ESA.

"Bearing in mind the socio-economic consequences, the fate of glaciers in a future climate is something ESA views seriously."

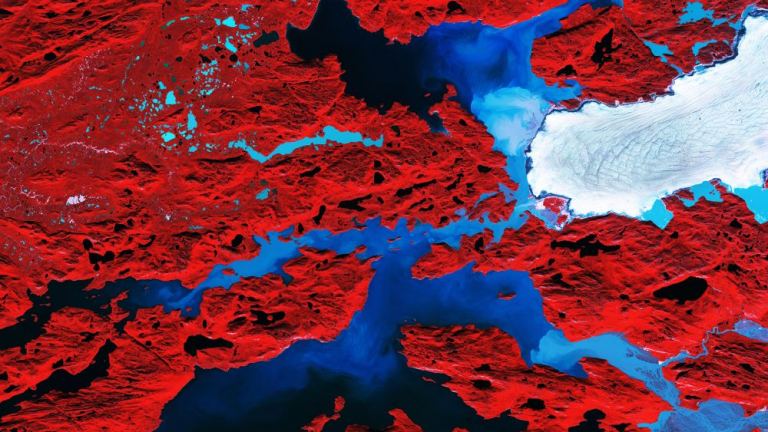

Argentina's Upsala Glacier has retreated more than 3 km in 15 years (Copernicus Sentinel data (2016)/ESA/CC BY-SA 3.0)

Argentina's Upsala Glacier has retreated more than 3 km in 15 years (Copernicus Sentinel data (2016)/ESA/CC BY-SA 3.0)

On A Personal Note

I doubt many Universe Today readers are that skeptical about climate change. There's a massive wall of evidence backing it up. Sometimes the evidence isn't scientific, but personal.

In the town I grew up here in Canada, and the town I still live in at the age of 52, we have our own glacier. It's perched high up in the mountains, plainly visible day by day, year over year, to anyone who wants to look at it.

It's even a hiking destination, for those who are prepared and experienced enough to head into the back country.

There's a very complete, distributed photographic record of that glacier's retreat over the last few decades. I bet everyone who lives here, or who has ever visited here, has taken pictures of it. It's a stunning sight, an icon in our community.

As we experience increasingly hot, dry summers, with smoke from distant forest fires blanketing our region for weeks at a time, we can look up at our receding glacier, glimpsing it through the smoke, and wonder when we'll ever take climate change seriously as a society.

It's not just a pretty landmark. This glacier is part of our watershed, releasing water throughout the summer that helps keep our community viable. It also feeds our hydroelectric power system, and keeps salmon populations viable in local rivers.

Glaciers fulfill that same function all around the world, in some of the world's most populous areas. How will communities function without them?

This article was originally published by Universe Today. Read the original article.